- Home

- Christopher Moore

1867 Page 4

1867 Read online

Page 4

Locked once again in opposition, his causes and ambitions further than ever from becoming realized, Brown went from fury to a kind of despair. Brown’s newspaper poured abuse on the governor general who had hobbled Brown and assisted Macdonald, and the reformers launched a court challenge to the double shuffle. When they lost, Brown observed bitterly that the presiding judge was William Draper, Macdonald’s mentor and himself a tory premier from the bad old days before responsible government. But Brown’s condemnations began to go beyond personalities. He began to condemn not just Macdonald, Cartier, the judges, and Sir Edmund Head, but the constitutional system that had made possible his humiliation.

Over the next months, the Globe began to sound steadily more like the Clear Grits. “Responsible government,” said the paper in February 1859, “has not realized the expectations of its promoters. Men begin to pronounce it a failure.” Brown spoke the same epitaph in a political speech. Given the enduring existence of two incompatible popular wills – French Canada’s and English Canada’s – he said sadly, “responsible government could only end in failure.” And with the union and parliamentary government simultaneously discredited, the Globe began to proclaim that dissolution of the union and a presidential constitution for Canada West were the likely choices to replace them. Sir Edmund Head’s tampering with the usages of the constitution, said the Globe, had done more to Americanize Canadian institutions than all other influences combined. Brown began to consider the case for a written constitution on the American model, for separating the executive branch of government from the legislative, and for abandoning the attempt to govern Protestant, English Canada West and Catholic, French Canada East within one state.7

We need not grieve much for George Brown and his expulsion from office in 1858, any more than Careless, his mostly admiring biographer, did. The abrupt fall and sudden realignment of coalition ministries was a normal part of public life in a state like the Province of Canada, and Brown’s rivals should hardly be condemned for employing all the stratagems the laws provided. Even if Sir Edmund Head seemed partisan in his preference for Macdonald over Brown, the outcome seemed to confirm the governor’s real-politik judgement that Brown’s rivals offered a better prospect of political stability. The double shuffle is hardly an edifying part of Canadian political history, but the mere question of who deserved to get in and who deserved to go out in the summer of 1858 need hardly disturb us now.

If, however, the disasters and embarrassments of the double shuffle had permanently soured George Brown on parliamentary government, the consequences might have been momentous. Brown’s aspirations and grievances were attuned to those of Canada West voters. As both its leading politician and its dominant newspaperman, he was superbly placed to guide and channel its political choices. Had he repudiated the union with Canada East and the British parliamentary tradition, he would have given an enormous boost to Clear Grit radicalism. A Clear Grit Brown, harnessing the West’s powerful sense of destiny, its impatience with compromise, and its anger at the French, would have pointed the way toward an Ontario without Quebec, and to a presidential system of government that aspired toward direct, rather than representative, democracy.

Such was not to be. John A. Macdonald would have been delighted to raise the loyalty cry and to campaign against George Brown as an annexationist and a traitor, and all the benefits of union, notably the skyrocketing growth and prosperity of Canada West, would have been marshalled on Macdonald’s side. Brown himself, whatever his frustration and his anger, was in the end too astute a campaigner and too much a patriotic British constitutionalist to plump wholeheartedly for such radical change. All his life he had been devoted to reform, but he had always insisted that true reform was the cause of representative, parliamentary democracy. In the wake of the double shuffle, he may have been tempted by the Clear Grit vision of an Upper Canadian paradise and vengeance on his tormentors. But only briefly. Before long, George Brown returned to the parliamentary system.

He remained the governmental impossibility. He was less likely than ever to form a government. In many ways, he was too zealous for the compromises that union politics required. Yet he returned to the parliamentary process. He seems to have returned to a root belief: that even a parliamentarian permanently in opposition had a role to play and a contribution to make. His return insured that, no matter how vigorously the Canadians debated union, disunion, and federalism in the 1860s, they would do so within the forms of the parliamentary system.

The analogy between George Brown and Preston Manning with which this chapter began is real enough. Manning acknowledged it when he named his modern party “Reform” and listed George Brown among its patron saints. But nineteenth- and twentieth-century Reformers part company at the point where Brown rededicated himself to parliamentary struggle. Preston Manning’s late-twentieth-century Reform Party promised to change the process of Canadian politics, not merely to exchange the Outs for the Ins. “To give effect to the common sense of the common people,” the platform of the modern Reform Party endorsed “direct consultation, constitutional conventions, constituent assemblies, national referenda, and citizens’ initiatives” to involve citizens directly in government. Its leader mused about impeaching unpopular prime ministers, and endorsed the recall of members of Parliament who followed their own judgement over their constituents’ wishes.8

The views of the modern Reformers were ones the Clear Grits would have understood. Like the Clear Grits, they expressed a scepticism about representative democracy far deeper than anything George Brown permitted his party to embrace. In its impatience with representation, however, the Reform Party was not nearly so radical in the twentieth century as the Clear Grits were in the mid-nineteenth. All twentieth-century parties from right to left had grown impatient with representative democracy. Radical, threatening, even “impossible” in other ways, the modern Reform Party was close to the centre of Canadian political culture in its belief that direct democracy and democracy itself were synonyms. All parties had ceased to see themselves as caucuses of representatives. They all sought to present a single message, marketed to a mass audience by a single leader. Inevitably, their efforts to forge a direct bond between leaders and the people downgraded legislatures and those who sat in them – except as election-night tally sticks to determine which leader achieved power. As one result, the role of legislatures in twentieth-century constitutional discussions was minuscule, by apparently unanimous consent.

George Brown, on the other hand, returned to the representative democracy that was the central faith of nineteenth-century politics in British North America. In his biography, Maurice Careless located Brown’s return to the parliamentary faith in a single event, the great reform convention at St. Lawrence Hall in Toronto in November 1859. Because of Brown’s choices, St. Lawrence Hall, still standing on Toronto’s King Street East, deserves to rank among the sites where confederation was made. Careless recreated the drama of the convention and its climax, “when even the gods and goddesses disporting on the ceiling of St. Lawrence Hall seemed to hang still and breathless in the yellow gaslight, far over the tall figure that now strode to the front of the platform.” George Brown was about to call for a federal union between Canada West and Canada East.9

Brown’s task in the convention he had organized was not to deny Canada West’s anger and ambitions, but to channel them into a renewed parliamentary campaign. His solution was federalism. To end Canada East’s interference in Canada West’s affairs, they would split the union into “two or more local governments” for Canada East and West. In 1859, western alienation still pointed toward separation, and when Clear Grit calls for a pure-and-simple dissolution roused cheers, Brown went far to accommodate them. The convention’s final resolution declared there would only be “some joint authority” to regulate matters of mutual interest between what would be two largely autonomous provinces.

In 1859, George Brown professed himself satisfied with only a restricted and inexpensive central government. B

ut he talked no more of “organic change,” of abandoning British political traditions to pursue a presidential constitution. With a platform of federalism to propose, Brown no longer wanted to demand new political processes. The convention would leave it to the legislature to decide on the details of federal union. After the St. Lawrence Hall convention, Brown’s was still a minority party excluded from power. He was still derided or made a bogey by both conservatives and rival reformers. Yet Brown had accepted that, even as a minority politician, perhaps condemned to perpetual opposition, he could do something useful, could perhaps see his causes brought to attention and to fruition.

In 1864, Brown was proven right. In the interim, he had struggled against both radical reformers impatient for “organic change” and moderate reformers still reluctant to change the union at all. Sandfield Macdonald, the most moderate of reformers and the union’s warmest champion, had put aside the rep-by-pop principle and formed a government, in alliance for a time with Antoine-Aimé Dorion. Brown, meanwhile, had taken a break from politics and made his first return visit in Britain. The visit mostly confirmed his commitment to Canada, but while in Edinburgh, Brown, then forty-three, fell suddenly in love. Within five weeks he was married. Anne Nelson at once became his steadiest and most secure commitment. Friends declared that her influence made Brown less impetuous, more thoughtful and tranquil. Better educated and more widely cultured than he was, she could hold her own in discussion with him. Maurice Careless pointed to her, through her influence on Brown, as a plausible “mother of confederation.”

By the spring of 1864, Sandfield Macdonald was out of power, and Macdonald and Cartier had returned once more to the cabinet room. The constant effort to construct a government without the impossible man, who commanded the largest bloc of Canada West’s representatives but would only enter government if he could change the union to a federation, was coming to an end. Brown’s instinct that Parliament could provide a solution finally bore fruit in May 1864. Even though Macdonald and Cartier were in power, the legislature approved Brown’s resolution to create an all-party legislative committee on constitutional matters. Even John A. Macdonald voted in favour, and Brown himself was appointed chairman. Power eluded Brown as much as ever, but Parliament would listen to his ideas.

In the House committee, parliamentarians of all shades of opinion discussed the constitutional deadlock: Canada West’s insistence on voting power to match its population; Canada East’s refusal to surrender to an English and Protestant majority; the widespread reluctance to abandon the union; the persistent ambitions to unite all the British provinces of North America. When the committee reported to the legislature (just as the Macdonald–Cartier government collapsed), Brown got the chance to make his historic offer. On June 17, Brown stood up in the hot, crowded legislative chamber in Quebec City and broke the mould of union politics.

He offered to go into coalition with his hated rivals. He accepted the impossibility of forming a government of his own choosing, and offered to sustain Macdonald and Cartier in office. They had only to accept the constitutional solutions that his parliamentary committee had recently endorsed: either federation – a federal union of Canada East and West – or confederation, which would include the Maritime colonies and potentially the North-West as well. Macdonald and Cartier swiftly agreed to make the pursuit of these alternatives into government policy. Amid cheers and handshakes, politicians who had been at each other’s throats for a decade told each other they had broken the political deadlock.

From the perspective of the 1990s, what was most striking about Brown’s offer is how much it was a parliamentary negotiation and a parliamentary accommodation. No single party could impose a solution to the problems of governing the united Canadas. No party commanded enough support to command the legislature, and no one-party policy would have been accepted in good faith by the others. Brown, however, had been proven right in his trust that, in a flourishing parliamentary system, where the voters’ elected representatives had real power to make both governments and policy, even a “governmental impossibility” could have a decisive impact.

The united Province of Canada has had an historical reputation, above all else, for political deadlock and for squalid deal-making. Professor Russell spoke for the late-twentieth-century mainstream when he dismissed parliamentary government at the time of confederation as a top-down form of democracy, obeying traditional élitist theories that are no longer tolerable today. But the union’s parliamentary government had defenders. In a heterodox study of Ontario’s political traditions, Professor S. J. R. Noel wrote that “in the United Canadas, the combination of responsible government and brokerage politics produced a system in which practically all the important areas of public policy … were dealt with through the processes of bargaining, deal-making and compromise: in other words, almost everything was legitimate grist to the political mill.… At its best it was innovative, practical, and wonderfully civilized.” Professor Noel declared that the political system of the Canadas in the 1860s “was in some respects in advance of any other in the world at that time.”10

Professor Russell – and presumably Preston Manning – would dismiss all this civilized parliamentary bargaining because it was done by “élites.” Certainly most politicians of the confederation era were wealthier, more prominent, and more successful than the mass of their supporters – much as politicians were in the late twentieth century. But they hardly enjoyed the kind of quasi-feudal authority suggested by “top-down democracy.” Politicians like George Brown and John A. Macdonald (essentially self-made successes, neither of whom received leadership as a birthright) were close to their electors. Macdonald is said to have known by name everyone who voted for him in Kingston, and (since voting was mostly done in public) everyone who opposed him, too. He and his rivals were elected on electoral franchises as broad as any then existing in the world, and they frequently staked their seats upon the support of an active, confident, well-informed, and changeable electorate. When they brokered the deal that broke the deadlock in June 1864, Macdonald, Brown, and Cartier had every right to believe that they represented the broad mass of the electorate which had recently put them into the legislature.

George Brown’s moment in government was brief. In the two vital conferences where confederation was negotiated, and in the parliamentary debates that followed, he was a powerful force. But he was not in the end a government man, and not all the elements of the new Canadian constitution pleased him. Once confederation was settled, Brown no longer had any wish to sit in cabinet with his old rivals. He left the coalition in the summer of 1866, eager to see traditional party lines restored.

He never did become quite the white-haired patriarch that Careless says we have made him. In 1880, not entirely weaned from irascibility and impulse, he got into a struggle with a dismissed employee who came into his Globe office to complain. The employee had a gun, and it went off. Shot in the leg, Brown minimized the extent of the wound, but it became infected and he died. He was sixty-two.

It remains striking that a man so stiff-necked about his own principles and so ready to denounce those of others, above all so uneasy about co-operation and compromise, was also a parliamentary man. George Brown’s career suggests the strengths of nineteenth-century parliamentary politics. Even Brown – in the mainstream view a dangerous fanatic who preferred his principles to power and didn’t much care whom he offended – hewed to the conventions of parliamentary process and parliamentary authority.

In the deal-making of the late twentieth century, by contrast, Canadian politicians acted as if they felt trapped in parliamentary forms, which they tried as much as possible to circumvent. By general consent, and certainly without a murmur of protest from parliamentarians, the legislatures played no significant part in the patriation of 1982, the Meech Lake accord of 1987, or the Charlottetown accord of 1992. (Rarely, they could play a negative role, as in 1990, when procedural rules enabled a single Manitoba legislator to disrupt the

careful ratification schedule that the triumphant first ministers had decreed.) In the late twentieth century, only leaders of parties in power had any place in constitutional deal-making. There was no place for the ideas of a party that could not hold power. In the 1990s, a sectional party could not represent its region in constitution-making unless it achieved power, and it could only achieve power in Ottawa by ceasing to speak for one section.

Had the rules of the 1990s applied in the 1860s, George Brown’s persistent inability to form a government would have precluded him (and his party) from any role in settling the constitutional crisis of the Province of Canada. In the 1860s, however, when parliaments were powerful, a seat in Parliament promised influence at the constitutional table. Even a governmental impossibility like George Brown preserved his faith in parliamentary government out of a belief that the people were represented by legislatures, not by first ministers alone. And that belief was ultimately rewarded. Brown was able, as a fiercely sectional partisan, to be a vital participant in brokering a deal acceptable to many rival sections.

To see how a sectionalized political society sincerely dedicated to parliamentary process handled constitutional challenges in the midst of deadlock, we have only the 1860s to observe. We can follow George Brown and his rivals-turned-partners to Charlottetown, where another parliamentary accommodation had brought a diverse collection of politicians from the Atlantic provinces together to meet them.

* The electoral franchise and its exclusions are considered in more detail in Chapter Six.

* Maybe not. The “provincial equality” proposed by advocates of the Triple-E Senate has been criticized on rep-by-pop grounds. And when the Charlottetown accord proposed to guarantee Quebec one-quarter of the seats in Parliament, rep-by-pop did indeed become controversial again.

* There was an ancient logic to this odd requirement. When kings actually ruled, parliaments existed not to govern but as a check upon the government of the Crown. Hence a parliamentarian who agreed to become an adviser to the Crown – a cabinet minister, in other words – was about to serve two masters: the king and the people. It was thought proper that he should secure the consent of his electors before doing so. As the parliament took control of government, and the king ceased to rule, the two-masters problem became moot. But constitutional usages die hard. The obligation on a new cabinet minister to seek re-election survived past confederation.

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

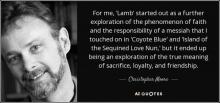

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

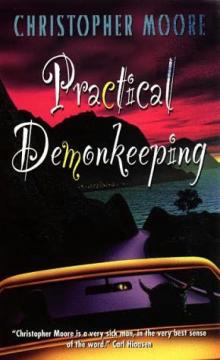

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1