- Home

- Christopher Moore

1867 Page 3

1867 Read online

Page 3

Once responsible government (and francophone influence) was assured, however, the voters of Canada East had what they needed from that reformist alliance. They drifted toward more-conservative concerns – notably the preservation of their language, faith, and traditions against English Protestant onslaughts. Reformers in Canada West also moved on – to issues such as separation of church and state. Since French Canadians understood these as code for an assault upon their religion, indeed upon their whole society, the alliance of English and French reformers soon fell apart. As long as George Brown’s newspaper was raising the alarm about “papal aggression” and proclaiming “no permanent peace in Canada until every vestige of church domination is swept away,” there was not much likelihood of restoring an Anglo–French reform coalition. A new and longer-lasting partnership between French and English leaders of the union was forged. It was conservative rather than reform-minded. Its great names were George-Étienne Cartier, who was LaFontaine’s political heir, and John A. Macdonald, who was Brown’s nemesis.

By the 1850s, when George Brown took a seat in the legislature, Canada West’s reformers had detached themselves from those of Lower Canada – and put themselves out of power. Brown seemed to have imprisoned himself in the role of regional spokesman, eyed with suspicion and hostility by most of Lower Canada and by advocates of Anglo–French co-operation. The third great principle Brown came to advocate during the 1850s solidified his regional power, even as it seemed to preclude him from any larger role. This was the principle most of all that made Brown a governmental impossibility. He called it “rep-by-pop.”

Representation by population is another apparently uncontroversial proposition.* It proposes that all votes should be of the same weight, and that communities of equal size should have equal representation in the legislature. In the union of the Canadas, however, representation by population had been overruled by a competing principle, sectional equality.

When the union was made in 1841, sectional equality had been an essential part of Britain’s plan to control and assimilate the French-speaking population. Francophone Lower Canada, despite its larger population, had been compelled to accept only the same number of assembly seats as Upper Canada, instead of the clear majority that “rep-by-pop” would have given it. But within a decade, constant immigration to Upper Canada – the Brown family was part of that migration – had reversed the proportions. Suddenly sectional equality became a protection for the French Canadians against their shrinking relative numbers. At just that point, Upper Canadian reformers began to campaign for rep-by-pop – more seats for Upper Canada, in effect, and probably more seats for Upper Canadian reformers.

It is easy – it was easy in the 1850s – to make sectional equality seem little more than cynical gerrymandering. Each section of the united Canadas, after all, had denounced sectional equality when its numbers were larger and embraced it when outnumbered. But the defence of sectional equality was, in its way, as principled as rep-by-pop. One of its great defenders was an old reform ally of George Brown, Francis Hincks.

Francis Hincks is mostly known to historians as a master financier. He could work out deals of astounding complexity, which usually proved to be of substantial benefit to his friends. The most notorious of these was “The Ten Thousand Pounds Job” of 1852, when his government guaranteed some previously risky private bonds. The bonds naturally jumped in value, enriching Hincks himself, at the expense of much of his reputation, and obliging his withdrawal from Canadian politics for more than a decade.

But deal-maker Hincks was also one of the architects of the politics of the union of the Canadas. He moved easily between Montreal and Toronto, and his legwork had fused the mutually suspicious blocs led by Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine into the reform majority that had secured responsible government. When reformers like Brown endangered that French-English alliance, Hincks stood by it. “The truth was,” said Hincks in 1853, as he demolished George Brown’s arguments for rep-by-pop, “that the people occupying Upper and Lower Canada were not homogeneous; but they differed in feelings, language, laws, religion and institutions, and therefore the union must be considered as between two distinct peoples, each returning an equal number of representatives.”6

Hincks understood – as all the really successful politicians of the union eventually did – that so long as Canada East and Canada West were joined together, Anglo–French alliances were the key to power. Alliances had to be built on trust, and trust was founded on an equality that would outlast any particular election or census. To give either side predominant influence over the politics of both could only destroy the other side’s trust in the union itself. Sectional equality had become the raison d’être of a state originally intended as a machine for assimilation. That was why reformer Hincks, the sectional-equality man, dismissed fellow reformer Brown, the apostle of rep-by-pop, as a governmental impossibility.

Yet it was not hard, at least in Canada West, to find justice in Brown’s principle, too. The Globe and George Brown exulted in Canada West’s size and prosperity, and at the same time they seethed with indignation that their region lacked the political clout to which its size and wealth and confidence made it feel entitled. It was no abstract indignation, either. Sectional equality meant that the cohesive bloc of French-Canadian legislators needed only a few supporters from Canada West to impose policies most of Canada West’s voters and their representatives might oppose. During the 1850s, George Brown had conceived a passion for rep-by-pop, and it was shared by masses of Upper Canadian voters.

Francis Hincks the reformer – apostate reformer, in Brown’s eyes – was not the only Upper Canadian ready to defend the union, even in the face of such consequences. Canada West’s conservatives, including John A. Macdonald, who was rising to leadership among them, were also willing to forsake Protestant solidarity for the sake of the French–English sectional alliance. Macdonald could justify that alliance as essential to racial harmony and to the preservation of the union, but it also put him and his tory colleagues into power for much of the 1850s and 1860s. As LaFontaine’s heir, Cartier led the big bloc of francophone legislators. As long as each section was equal in parliament, Macdonald needed only to deliver a handful of anglophone seats in order to give the Macdonald–Cartier partnership something close to a permanent majority.

Macdonald and his supporters saw themselves as adroit politicians, building the coalitions of interests that union politics demanded. Brown’s reformers drew a different lesson: “sectional equality” meant the imposition of French Canada’s agenda, no matter how unpopular, upon Canada West whenever Canada East got the support of a few western collaborationists, who would sacrifice western interests for the sake of the alliance that kept them in power. Brown concluded that “sectional equality” was a high-sounding phrase that masked an unscrupulous advantage for Canada East over Canada West. He had his own ugly phrase for it: “French domination,” and later simply “French Canadianism.”

The fight between sectional equality and rep-by-pop lasted for a decade, and the survival of the union was always at stake. If French Canada would not accept rep-by-pop, would Canada West’s reformers tolerate sectional equality for the sake of the union? Some would, to Brown’s fury and frustration. John A. Macdonald, embattled-but-ever-resourceful leader of the small band of Upper Canadian conservatives, gleefully built his “Liberal–Conservative” party by drawing union-minded reformers, like Francis Hincks, into his coalitions with Cartier’s Lower Canadian conservative bleus.

But other reformers were actually more radical than Brown in their attack on sectional equality and on other institutions of the union. Brown himself had dubbed them the “Clear Grits.” If the union itself had to be sacrificed in order to bring in the rep-by-pop principle, the Clear Grits were ready to kill the union.

Even more than George Brown and his fierce parliamentary liberalism, the Clear Grits constitute a demolition of the legend that “democracy” was unknown to mid

-nineteenth-century Canadians. Even today, enacting their platform would constitute a radical remaking of Canadian politics. In the 1850s, their victory would have produced a constitutional earthquake. The Clear Grits – “all sand and no gravel, clear grit all the way through” – intended to scrape away all the undemocratic and unegalitarian elements of their society to produce a pure democracy in Upper Canada. Like George Brown, they were eager to sweep away religious privilege and the injustices suffered by Canada West in the union. But they went much farther than Brown.

The Clear Grits attacked privilege of every other kind, too. Brown wanted the Queen to be a symbolic ruler, but still a revered one. The Clear Grits would replace the monarchy with a directly elected head of government. Brown had extolled parliamentary rule. Clear Grits proposed that every public official, from the governor down to local judges and officials, should be directly elected and wield power directly. They believed public institutions must be cheap, simple, efficient, and as local as possible: every man should be his own lawyer as well as his own political representative. They wanted legislators limited to fixed two-year terms. They had not brought themselves to admit the equality of women, but they would give a vote (and a secret ballot) to every adult male.

Of course, Clear Grits were rep-by-pop campaigners, for they were fierce partisans of the unfettered rule of the majority. Indeed, they were ready to be western separatists rather than compromise with the French Canadians of Canada East. Ready to junk British parliamentary traditions, they were also willing to consider annexation to the United States more favourably than dependence upon Catholic Quebec. But the radicalism of the Clear Grits did not mean they were fanciful, impractical theorists. They drew on close-by examples from the United States, but they also reflected British radicalism. Many British emigrants who had gladly left behind a Britain of privilege and inequality were ready to listen.

Clear Grits celebrated the sturdy self-reliance and innate egalitarianism of the farmers who had been the main supporters of rebellion in 1837, and the romance of 1837’s lost cause became part of Clear Grit appeal. Upper Canada was a land of farmers, and farmers’ votes were the essential source of electoral success. If the farmers of Upper Canada drifted into Clear Grit thinking, reform-minded politicians would have to consider drifting with them.

Brown had a moment when the constitutional dynamite of the Clear Grits – “organic change” was his shorthand for it – did attract him. His temptation began when the parliamentary system he had always extolled delivered him his most humiliating setback. George Brown tasted power in 1858 – for two days. Then he fell victim to the double shuffle.

The double shuffle of August 1858 is the kind of event that persuades historians not to write about nineteenth-century politics. It depends on such an accumulation of period detail and constitutional arcana that making it plausible is like trying to explain the notwithstanding clause to a visiting Martian. Nevertheless, the effort may be worthwhile. The obscurities of the double shuffle can help to suggest constitutional choices of the 1860s that echoed in the 1990s.

The fundamental fact of union politics was the diversity of political faiths and factions. The split between reformers and conservatives, compounded by regional and linguistic divisions, resulted in two sets of reform and tory caucuses, one each for Canada West and Canada East. Those blocs often divided into the alliance-minded (Hincks, the reformer, for instance) and the no-compromisers (the Clear Grits, for example). In addition, there were independents, who joined parties or followed leaders only on their own terms and schedules. Such diversity made for lively politics, frequent crises, and endless jockeying (sometimes subtle, sometimes startlingly ruthless) to make parliamentary coalitions and to build voter loyalties. If deal-making is the essence of politics, then the politics of the union of the Canadas was second to none in the world.

Brown’s moment of power in the summer of 1858 began with the fall of one coalition ministry and the fight to build another. Macdonald and Cartier’s government, caught in a compromise that had managed to alienate supporters on both edges of the coalition, had lost its majority and decided to resign. Barely six months had passed since a general election, and Brown seized his chance by offering to avert an election. He offered to see if he could assemble a legislative majority where Macdonald and Cartier had just failed. In association with Antoine-Aimé Dorion, leader of the French-Canadian reformers called the rouges, Brown went to see the governor general, a scholarly Englishman named Sir Edmund Walker Head.

We will see more of Antoine-Aimé Dorion and the rouges in another chapter. Suffice it here to acknowledge that French-Canadian politics was not monolithic. George-Étienne Cartier, secure in the approval of the church, a spokesman for conservative French-Canadian opinion, and approved by the tycoons of English Montreal’s Square Mile, might dominate politics in Canada East, but the rouges had inherited a minority tradition that was reformist and frequently secular-minded, if not actually anti-clerical, when such positions exposed them to fiercer attack in Catholic Canada East than Brown’s voluntaryism had to endure in Protestant Canada West.

As reformers, the rouges had some common ground with the western reformers, but only some. The rouges expressed anti-English grievances as vigorously as the reformers expressed anti-French ones, and the coalition was risky for both partners. Dorion and his group were to join George Brown, universally condemned in Canada East as a bigot, an anti-Catholic, and an Upper Canadian imperialist. For his part, Brown, the scourge of French domination and sectional equality, was proposing to lead his reformers into a government as dependent on the votes of Canada East as any of John A. Macdonald’s.

Brown saw this as his moment to show he was not merely a sectional protest leader – or a bigot either. He and Dorion promised a government that would prove reform ideas were not impossible, and that they could save the union rather than destroy it. Brown and Dorion promised to introduce rep-by-pop while safeguarding the position of Canada East, to build a secular education policy without threatening Catholic education, and generally to advance Canada West’s interests without damaging Canada East’s.

Governor Head seems to have shared the widespread suspicion that both Brown and Dorion were dangerously radical and their principles a threat to the union, but they were entitled to form a government. They assembled a cabinet and thrashed out the basis of an agreement between their parties.

Brown and Dorion never had a chance to flesh out their promises or test them in action. Their new government had to meet the legislature and win a vote of confidence. Under the custom then still prevailing, politicians who accepted public office were obliged to resign their seats and seek the approval of their constituents for their decision to serve in the Crown’s administration. So Brown, Dorion, and all the members who had become cabinet ministers had to resign and watch from the gallery as their government faced its first legislative test one day after they took office.* Their absence ensured the defeat of their government.

At this point, Brown and Dorion wanted a general election, in which they could run as a government seeking a mandate rather than as a collection of opposition members. They asked Governor Head to dissolve the legislature. But Sir Edmund refused. In the 1850s, as in the 1990s, granting or refusing dissolution of the legislature was one of the few enduring powers of a governor general. Head used his authority to snub Brown and Dorion’s advice about a new election. Already he had an alternative government at hand.

The ever-inventive Macdonald and Cartier had put their problems behind them, rebuilt their coalition, and recruited some new supporters. They were ready to try again, and Governor Head was ready to let them. He invited Macdonald and Cartier back into power. In just three days, Macdonald and Cartier had resigned, been replaced, defeated their successors in the House, built a new coalition, and regained office. Once again they were in and Brown was out.

Even after going back through the revolving door on the cabinet room, Macdonald and Cartier had to pull one more

rabbit from their top hat of parliamentary skills, for they had to evade the problem that had beaten Brown and Dorion: the need to resign their seats and seek personal re-election upon accepting office. Macdonald and Cartier proved equal to the challenge by inventing the double shuffle.

Ministers who merely changed cabinet posts did not need to be re-elected. So, as if they had never left office, Macdonald and Cartier and their ministers solemnly shuffled the cabinet offices amongst themselves, and then after a day reshuffled them. Each minister recovered his old position, and Macdonald blithely told the House the law had been satisfied. While the Brown–Dorion team was still out seeking re-election to validate its members’ right to offices that had already been taken away from them, the Cartier–Macdonald team reoccupied its old cabinet posts and held on to its legislative seats. After two days in opposition, Cartier and Macdonald would stay in office for two more years – an eternity in the union’s lively politics.

Those two days were the only days George Brown would ever run a government. (Dorion had another brief stint in power in 1863–4.) His “short administration” was a humiliating failure. Opponents rejoiced that the disaster of a Brown government had been avoided, and happily denounced his greedy, short-sighted lust for power. They mocked him for abandoning his principles for office and then losing the office as well, proving he was not merely unworthy of political office, but also too inept to get it. More than ever, they said, George Brown had proved himself a governmental impossibility.

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

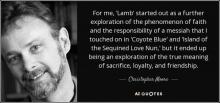

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

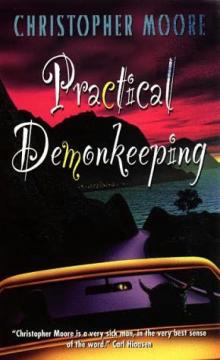

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1