- Home

- Christopher Moore

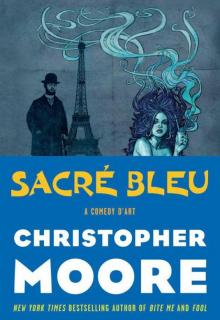

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Read online

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Part I: Sacred Blue

One: Wheat Field with Crows

Interlude in Blue #1: Sacré Bleu

Two: The Women, They Come and Go

Three: The Wrestling Dogs of Montmartre, Paris

Four: Pentimento

Five: Gentlemen with Paint Under Their Nails

Interlude in Blue #2: Making the Blue

Six: Portrait of a Rat Catcher

Part II: The Blue Nude

Seven: Form, Line, Light, Shadow

Interlude in Blue #3: A Frog in Time

Eight: Aphrodite Waving Like a Lunatic

Nine: Nocturne In Black and Gold

Ten: Rescue

Eleven: Camera Obscura—

Twelve: Le Professeur Deux

Thirteen: The Woman in The Storeroom

Fourteen: We Are Painters, and Therefore Somewhat Useless

Fifteen: The Little Gentleman

Sixteen: It’s Pronounced Bas’Tahrd

Seventeen: In The Latin Quarter

Eighteen: Trains in Time

Nineteen: The Dark Carp of Giverny

Twenty: Breakfast at The Black Cat

Twenty-one: A Sudden Illness

Twenty-two: The End of The Master

Part III: Amused

Twenty-three: Closed Due to Death

Twenty-four: The Architecture of Amusement

Twenty-five: The Painted People

Interlude in Blue #4: A Brief History of the Nude in Art

Twenty-six: The The, The The, and the Color Theorist

Twenty-seven: The Case of The Smoldering Shoes

Twenty-eight: Regarding Maman

Twenty-nine: Two Grunts Rising

Thirty: The Last Seurat

Epilogue in Blue: Then There Was Bleu, Cher

Afterword: So, Now You’ve Ruined Art

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Christopher Moore

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Part I

Sacred Blue

I always feel like a traveler, going somewhere, toward some

destination. If I sense that this destination doesn’t in fact

exist, that seems to me quite reasonable and very likely true.

—VINCENT VAN GOGH, JULY 22, 1888

Well, I have risked my life for my work, and it has cost me

half my reason—

—VINCENT VAN GOGH, JULY 23, 1890

Prelude in Blue

This is a story about the color blue. It may dodge and weave, hide and deceive, take you down paths of love and history and inspiration, but it’s always about blue.

How do you know, when you think blue—when you say blue—that you are talking about the same blue as anyone else?

You cannot get a grip on blue.

Blue is the sky, the sea, a god’s eye, a devil’s tail, a birth, a strangulation, a virgin’s cloak, a monkey’s ass. It’s a butterfly, a bird, a spicy joke, the saddest song, the brightest day.

Blue is sly, slick, it slides into the room sideways, a slippery trickster.

This is a story about the color blue, and like blue, there’s nothing true about it. Blue is beauty, not truth. “True blue” is a ruse, a rhyme; it’s there, then it’s not. Blue is a deeply sneaky color.

Even deep blue is shallow.

Blue is glory and power, a wave, a particle, a vibration, a resonance, a spirit, a passion, a memory, a vanity, a metaphor, a dream.

Blue is a simile.

Blue, she is like a woman.

One

WHEAT FIELD WITH CROWS

Auvers, France, July 1890

ON THE DAY HE WAS TO BE MURDERED, VINCENT VAN GOGH ENCOUNTERED a Gypsy on the cobbles outside the inn where he’d just eaten lunch.

“Big hat,” said the Gypsy.

Vincent paused and slung the easel from his shoulder. He tipped his yellow straw hat back. It was, indeed, big.

“Yes, madame,” he said. “It serves to keep the sun out of my eyes while I work.”

The Gypsy, who was old and broken, but younger and less broken than she played—because no one gives a centime to a fresh, unbroken beggar—rolled an umber eye to the sky over the Oise River Valley, where storm clouds boiled above the tile roofs of Pontoise, then spat at the painter’s feet.

“There’s no sun, Dutchman. It’s going to rain.”

“Well, it will keep the rain out of my eyes just as well.” Vincent studied the Gypsy’s scarf, yellow with a border of green vines embroidered upon it. Her shawl and skirts, each a different color, spilled in a tattered rainbow to be muted under a layer of dust at her feet. He should paint her, perhaps. Like Millet’s peasants, but with a brighter palette. Have the figure stand out against the field.

“Monsieur Vincent.” A young girl’s voice. “You should get to your painting before the storm comes.” Adeline Ravoux, the innkeeper’s daughter, stood in the doorway of the inn, holding a broom poised not for sweeping but for shooing troublesome Gypsies. She was thirteen, blond, and though she would be a beauty one day, now she was gloriously, heartbreakingly plain. Vincent had painted her portrait three times since he’d arrived in May, and the whole time she had flirted with him in the clumsy, awkward manner of a kitten batting at yarn before learning that its claws may actually draw blood. Just practicing, unless poor, tormented painters with one earlobe were suddenly becoming the rage among young girls.

Vincent smiled, nodded to Adeline, picked up his easel and canvas, and walked around the corner, away from the river. The Gypsy fell in beside him as he trudged up the hill past the walled gardens, toward the forest and fields above the village.

“I’m sorry, old mother, but I’ve not a sou to spare,” he said to the Gypsy.

“I’ll take the hat,” said the Gypsy. “And you can go back to your room, out of the storm, and make a picture of a vase of flowers.”

“And what will I get for my hat? Will you tell my future?”

“I’m not that kind of Gypsy,” said the Gypsy.

“Will you pose for a picture if I give you my hat?”

“I’m not that kind of Gypsy either.”

Vincent paused at the base of the steps that had been built into the hillside.

“What kind of Gypsy are you, then?” he asked.

“The kind that needs a big yellow hat,” said the Gypsy. She cackled, flashing her three teeth.

Vincent smiled at the notion of anyone wanting anything that he had. He took off his hat and handed it to the old woman. He would buy another at market tomorrow. Theo had enclosed a fifty-franc note in his last letter, and there was some left. He wanted—no, needed to paint these storm clouds before they dropped their burden.

The Gypsy examined the hat, plucked a strand of Vincent’s red hair from the straw, and tucked it away into her skirts. She pulled the hat on right over her scarf and struck a pose, her hunchback suddenly straightening.

“Beautiful, no?” she said.

“Perhaps some flowers in the band,” said Vincent, thinking only of color. “Or a blue ribbon.”

The Gypsy grinned. No, there was a fourth tooth there that he’d missed before.

“Au revoir, Madame.” He picked up his canvas and started up the stairs. “I must paint while I can. It is all I have.”

“I’m not giving your hat back.”

“Go with God, old mother.”

“What happened to your ear, Dutchman, a woman bite it off?”

“Something like that,” said Vincent. He was halfway up the first of three flights of steps.

“An ear won’t

be enough for her. Go back to your room and paint a vase of flowers today.”

“I thought you didn’t tell futures.”

“I didn’t say I don’t see futures,” said the Gypsy. “I just don’t tell them.”

“And what will I get for my hat? Will you tell my future?” Self-Portrait—Vincent van Gogh, 1887

HE SET HIS EASEL AT THE PITCHFORK JUNCTION OF THREE DIRT ROADS. Three wheat fields lay before him and a cornfield behind. He was nearly finished with the painting, the golden wheat under an angry blue-black sky swirling with storm clouds. He loaded his brush with ivory black and painted a murder of crows rising from the center of the picture into an inverted funnel to the right corner of the canvas. For perspective, so the painting wasn’t entirely about color on canvas, although many in Paris were beginning to argue that all painting was just color, nothing more.

He painted a final crow, just four brushstrokes to imply wings, then stepped back. There were crows, of course, just not compositionally convenient ones. The few he could see had landed in the field, sheltering against the storm, like the field workers, who had all gone to shelter since Vincent had started to paint.

“Paint only what you see,” his hero Millet had admonished.

“Imagination is a burden to a painter,” Auguste Renoir had told him. “Painters are craftsmen, not storytellers. Paint what you see.”

Ah, but what they hadn’t said, hadn’t warned him about, was how much you could see.

There was a rustling behind him, and not just the soft applause of the cornstalks in the breeze. Vincent turned to see a twisted little man stepping out of the corn.

The Colorman.

Vincent stopped breathing and shuddered, feeling in every muscle a vibration, his body betraying him, reacting to the sight of the little man as a recovered addict might convulse with cravings upon the first sight of the drug of his downfall.

“You ran from Saint-Rémy,” said the Colorman. His accent was strange, indistinct, the influence of a dozen languages poorly pronounced. He was round-bellied and slope-shouldered, his arms and legs a bit too thin for his torso. With his little cane, he moved along like a damaged spider. His face was wide, flat, and brown; his brow protruded as if to keep the rain out of the black beads of his eyes. His nose was wide, his nostrils flared, reminding Vincent of the Shinto demons in the Japanese prints his brother sold. He wore a bowler hat and a leather vest over a tattered linen shirt and pants.

“I was ill,” said Vincent. “I didn’t run. Dr. Gachet is treating me here.”

“You owe me a picture. You ran and you took my picture.”

“I’ve no need of you. Theo sent me two tubes of lemon yellow just yesterday.”

“The picture, Dutchman, or no more blue for you.”

“I burned it. I burned the picture. I don’t want the blue.”

The wind tumbled Vincent’s painting off the easel. It landed faceup on grass between the ruts in the road. Vincent turned to pick it up and when he turned back, the Colorman was holding a small revolver.

“You didn’t burn it, Dutchman. Now, tell me where the painting is or I’ll shoot you and find it myself.”

“The church,” Vincent said. “There’s a painting of the church in my room at the inn. You can see, the church is not blue in life, but I painted it blue. I wanted to commune with God.”

“You lie! I have been to the inn and seen your church. She is not in that painting.”

The first fat raindrop plopped on the little man’s bowler, and when he looked up, Vincent snapped his paintbrush, sending a spray of ivory black into the Colorman’s face. The Colorman’s gun fired and Vincent felt the wind knocked out of him. He grabbed his chest and watched as the Colorman threw his gun to the ground and ran into the corn, chanting, “No! No! No! No!”

Vincent left the painting and the easel, picked a single, crushed tube of paint from his paint box and put it in his pocket, then, holding his chest, he trudged down the road that ran along the ridge above town a mile to Dr. Gachet’s house. He fell as he opened the iron gate at the foot of the stone steps that led through the terraced garden, then crawled to his feet and climbed, pausing at each step, leaning on the cool limestone, trying to catch his breath before taking the next. At the front door he struggled with the latch, and when Madame Gachet opened it, he fell into her arms.

“You’re bleeding,” said Madame Gachet.

Vincent looked at the red on his hands. Crimson, really. Not red. A bit of brown and violet. There weren’t enough words for the colors. Colors needed to be free of the constraint of words.

“Crimson, I think,” said Vincent. “This is my doing. This is mine.”

VINCENT AWOKE WITH A START, GASPING FOR BREATH. THEO WAS THERE. He’d arrived from Paris on the first train after word came from Dr. Gachet.

“Calm, Vincent,” said Theo in Dutch. “Why this? Why this, brother? I thought you were better.”

“The blue!” Vincent grabbed his brother’s arm. “You must hide it, Theo. The blue one I sent from Saint-Rémy, the dark one. Hide her. Let no one know you have her. Keep her from him. The little man.”

“Her? The painting?” Theo blinked tears out of his eyes. Poor, mad, brilliant Vincent. He would not be consoled. Not ever.

“You can show it to no one, Theo.” Vincent convulsed with pain and sat upright in the bed.

“Your paintings will all be shown, Vincent. Of course they will be shown.”

Vincent fell back and coughed, a wet, jarring cough. He clawed at his trousers.

“Give it. Give it, please. The tube of blue.”

Theo saw a crushed tin tube of paint on the bedside table and placed it in Vincent’s hand.

“Here, is this what you want?”

Vincent took the tube and squeezed the last little bit of ultramarine blue out onto his finger.

“Vincent—” Theo tried to take his brother’s hand, but Vincent took the blue and smeared it across the white bandages around his chest, then fell back again, letting out a long rattling breath.

“This is how I want to go,” Vincent said in a whisper. Then he died.

Interlude in Blue #1: Sacré Bleu

The cloak of the Virgin Mary is blue. Sacred blue. It was not always so, but beginning in the thirteenth century, the Church dictated that in paintings, frescoes, mosaics, stained glass windows, icons, and altarpieces, Mary’s cloak was to be colored blue, and not just any blue, but ultramarine blue, the rarest and most expensive color in the medieval painter’s palette, the source mineral, more valuable than gold. Strangely enough, in the eleven hundred years prior to the rise of the cult of the Virgin, there is no mention in Church liturgy of the color blue, none, as if it had been deliberately avoided. Prior to the thirteenth century, the Virgin’s cloak was to be depicted in red—color of the sacred blood.

Medieval color merchants and dyers, who had been geared up for red since the time of the Roman Empire, but had no established natural source for blue, were hard-pressed to meet the demand that rose from the color’s association with the Virgin. They tried to bribe glass-makers at the great cathedrals to portray the Devil in blue in their windows, in hope of changing the mind-set of the faithful, but the Virgin and Sacré Bleu prevailed.

The cult of the Virgin itself may have risen out of an effort of the Church to absorb the last few pagan goddess-worshippers in Europe, some of those the remnants of worshippers of the Roman goddess Venus, and her Greek analogue Aphrodite, and the Norse, Freya. The ancients did not associate the color, blue with their goddesses. To them, blue was not even a real color but a shade of night, a derivative of black.

In the ancient world, blue was a breed of darkness.

Two

THE WOMEN, THEY COME AND GO

Paris, July 1890

LUCIEN LESSARD WAS HELPING OUT IN THE FAMILY BAKERY ON MONTMARTRE when the news came of Vincent’s death. A shopgirl who worked near Theo van Gogh’s gallery Boussod et Valadon had come into the bakery to put together her l

unch and dropped the news as blithely as if commenting on the weather.

“Shot himself. Right there in a cornfield,” said the girl. “Oh, one of those lamb pasties, please.”

She was surprised when Lucien lost his breath and had to steady himself on the counter.

“I’m sorry, Monsieur Lessard,” said the girl. “I didn’t know you knew him.”

Lucien waved to dismiss her concern and composed himself. He was twenty-seven, thin, clean-shaven, with a shock of dark hair that swept across his forehead and dark eyes so deeply brown that they seemed to draw light from a room. “We studied together. He was a friend.”

Lucien forced a smile at the girl, then turned to his sister Régine, six years his senior, a fine, high-cheeked woman with the same dark hair and eyes, who was working down the counter.

“Régine, I must go tell Henri.” He was already untying his apron.

Régine nodded and turned away quickly. “You must,” she said. “Go, go, go.” She waved him off over her shoulder and he could see that she was hiding tears. They weren’t tears for Vincent—she had barely known him—but for the death of another mad painter, which was the Lessard legacy.

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1