- Home

- Christopher Moore

1867 Page 5

1867 Read online

Page 5

CHAPTER TWO

Charles Tupper Goes to Charlottetown

SIR CHARLES TUPPER died in 1915, in his ninety-fifth year. In his final years, he made periodic excursions to the Vancouver home of his son Charles Hibbert Tupper, but his residence at the end was an English country estate with the Wodehousian name of Bexleyheath. It is an enormous leap – almost too much for one life to contain – from the young political scrapper who entered Nova Scotia’s colonial assembly in 1855 to this ancient baronet of Bexley. It seems odd to us, now, how so many Canadian nation-builders, even those born and raised in Canada, took themselves off to Britain in retirement, preferring to die in the “old country,” even if, like Tupper, they had never been young there. The last Canadian political leader to choose a British deathbed was R. B. Bennett, child of Hopewell Hill, New Brunswick, who in 1938 removed himself to an English village called Mickleham, wangled himself a viscountcy, and died impersonating an English gentleman. Today, of course, Tupper and Bennett would be more apt to die in Palm Beach or Lyford Cay, which at least have weather to commend them. As the natural refuge of superannuated Canadian leaders, Britain has become unimaginable.

So Tupper at the end of his life cuts an incomprehensible figure. The last of the thirty-six fathers of confederation, all his contemporaries long dead, sits, a huge old ruin in a fur collar with a blanket over his knees, chauffeured about the damp English countryside in some clanking black motor car, doubtless trying to comprehend the horribly modern slaughter of young Canadians at Ypres and Festhubert, gradually letting it go.

That unedifying twilight makes it hard to recapture the energetic nation-building young Tupper of the 1860s. And Tupper himself does not help us. He left two volumes of memoirs and an authorized Life and Letters – all so bland, superficial, and sanitized that they tell us little of his achievements and almost nothing about him. His personal papers were, in historian Peter Waite’s phrase, “not so much laundered as starched.” The destruction of most of what was worthwhile in them has made it almost impossible to flesh out the stiff cardboard of his public image with anything human and tangible.

He had his admirers. There are many reports of the Tupper who always overflowed with energy and enthusiasm, who kept his black medical bag under his parliamentary desk and would offer medical help at any time. Those who liked him said he was bluff and four-square and immovable in his determination. He was full of “a characteristic which may be defined in a favourable sense as audacity,” as one journalist put it. “In repose, even, he looked as if he had a blizzard secreted somewhere about his person,” said a fellow MP. With the wives of his friends and colleagues, he was said to be gallant and flirtatious, never too busy to hear some medical confidence, organize an outing, or simply present a flower from the garden.1

Those who liked him said he was dogged in adversity. Actually he was a bully. When he had power, he was constantly eager not merely to defeat but to humiliate his rivals. Historian Waite, who made a wonderful biography from the well-preserved papers of Tupper’s fellow Nova Scotian John Thompson, notes in it the legend that “Tupper” arose from the French tu perds, “you lose.” For the weak or dependent, Tupper was hardly the trusted companion his more secure friends imagined. He was married for sixty-five years, and friends insisted the marriage was happy and close, but letters – vanished from Tupper’s papers but preserved in Thompson’s – suggest a Tupper who was aggressively sexual. Waite reports how Tupper, a Baptist and a minister’s son, once bullied Thompson into taking him to mass, simply to pursue a young Catholic woman he was attracted to. That and a hundred other incidents might have been simply flirtatious, but Waite also cites the Washington typist who alleged in a legal action that Tupper got her pregnant, talked her into an abortion, and vanished. Her complaint was unproven, and her court case, denounced as a blackmail, was either abandoned or privately settled. Still, such stray details give an unpleasant inkling of the kind of bullying endured, if half the rumours are true, by vulnerable citizens upon whom Tupper forced his attentions.2

Tupper’s public record was long and distinguished. After the great editor and statesman Joseph Howe brought Nova Scotia responsible government in 1847 by welding supporters of reform into a disciplined party with broad electoral support, Tupper helped bring the conservative party back into contention by transforming it from an aristocratic Anglican clique into a broad coalition of middle-class Protestants and Catholics. He personally came to public attention by unseating Howe himself in a head-to-head contest. Howe acknowledged Tupper as a worthy foe, both as a campaigner and a strategist – though he regretted that young Tupper, for all his talents, could never simply argue a principle; he had to attack the good name of his opponents, too. As premier of Nova Scotia, Tupper led the confederation negotiations, and against deep opposition he brought his province into confederation. Moving to the federal stage, he became an indefatigable cabinet minister, ambassador, and political fixer, and finally prime minister of Canada.

Two deep scars flaw the record of nearly fifty years in public life. The more visible of the two was inflicted in 1896, after Tupper returned from nearly a decade as Canadian High Commissioner to Britain to become party leader and prime minister. He had to face the voters at once, and was swept from office. Defeat left him the shortest-serving prime minister ever. With fewer days in office than Kim Campbell or John Turner, Tupper the prime minister ranks merely as one of the four hapless Conservatives – Waite’s Thompson was another – who briefly held the office after the death of Sir John A. All have been totally eclipsed by Macdonald’s halo and by the bright light of Wilfrid Laurier’s sunny ways, which flared out upon Tupper’s rout and outshone all rivals for fifteen years. Tupper, the last of the futile four and the only one to face election, seems now diminished rather than elevated by having held the office, an asterisk prime minister, a trivia question.

The other deep flaw in Tupper’s record is the nasty business of Nova Scotia’s entry into confederation in 1867. At the very end of his term of office, Premier Tupper got confederation through without an electoral mandate and over the protests of many Nova Scotians. The unwilling province responded with fury, driving his party from office provincially and electing anti-confederates to eighteen of Nova Scotia’s nineteen seats in the first Canadian House of Commons. Tupper’s bullying of his province remains a complaint in Nova Scotia, part of the black legend of Maritime grievance against the Canadian union. Neither 1896 nor 1867 lends lustre to Charles Tupper’s political reputation.

But something Tupper did in 1864 deserves to loom large. Eighteen sixty-four was, like 1992, a summer of constitutional accord at Charlottetown. But the first constitutional Charlottetown was as much a success as the second was an embarrassment and a failure. The 1864 conference at Charlottetown transformed the pious, impractical ideal of confederation into a political program to be taken seriously. Charles Tupper more than anyone put in place the crucial factor that made success at Charlottetown possible in 1864. So it is worth giving some attention to how Charlottetown came to be and how Charles Tupper came to Charlottetown.

“It was the enthusiasm of Gordon of New Brunswick that gave the movement its real start,” reads the opening sentence of The Road to Confederation, Donald Creighton’s 1964 book about the shaping of the nation. Creighton was the pre-eminent Canadian historian of the 1950s and 1960s. His Road to Confederation, written just after his magisterial biography of John A. Macdonald, is a marvellous book, with wonderful detailing, strong ideas, and an unrelenting narrative drive to catch and carry the reader along. It’s much the most readable account of the confederation process. A reader comes away thinking that Creighton knew a lot about his subjects, and wondering why historians don’t often write like that.

For all the authority and readability of his work, however, historians began to react against Creighton even before his long life ended in 1979. His late-in-life role as a national scold, inveighing against bilingualism, liberals, women, the American empire, an

d the modern world in general, certainly diminished his stature. His dismissive contempt for anyone who resisted or questioned John A. Macdonald’s view of Canada (or was it Creighton’s own) provoked resistance as confederation itself ran into trouble. But historians were also made suspicious by his wonderful prose. Creighton’s narratives are so rhetorical, so persuasive, so dismissive of even the possibility of any other interpretation of events, that any critically attuned reader must suspect that many noteworthy alternates are being buried and denied. “The prince of pattern makers,” an historian recently called him, with just a hint that the pattern was as much imposed as discovered.

The sceptics are right enough. Much of Creighton’s steamroller version of confederation urgently needs to be reconsidered. Still, giving the storyteller his due, we have to inquire: who was this “Gordon of New Brunswick” to be honoured with the master storyteller’s first line? What could he have done to have given confederation “its real start”?

Gordon of New Brunswick was Arthur Gordon, lieutenant-governor of the province. Obviously we have come a long way, if an office now so wrapped and bound in absolute irrelevance could be the springboard of confederation. Creighton opened with Gordon for one reason. Gordon had provoked the Charlottetown conference into being.

Creighton, however, was not out to make Arthur Gordon a hero. He wanted Gordon for comic relief, a foil for his real heroes. In Creighton’s sketch, Gordon was the Bertie Woosterish son of an earl, just thirty-five in 1864 and unshakeably certain that he was meant to rule New Brunswick as an Imperial potentate. He had taken the job on the assumption that New Brunswick was meant to be ruled by expatriate autocrats, like any other corner of the British Empire, and he found responsible government a rude shock. Gordon thought it beneath his dignity to do anything but dictate to colonial politicians, whom he characterized as the “ignorant lumberer,” the “petty attorney,” and the “keeper of a village grog shop.”3

Gordon proposed a conference at Charlottetown because he wanted to unite Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, not British North America at large. Given his high opinion of the importance his office should have, he naturally assumed that the governors of the three provinces would take the lead in securing the union, and that he would govern it. He could not entirely ignore the people’s elected representatives, but what he proposed was an executive conference, a meeting of the three governors and their premiers. When that cosy conclave had approved the union, the dutiful premiers would be sent to secure the consent of their legislatures, while the governors arranged with the Colonial Office to have the change made. Gordon set about organizing a meeting of six, the three governors and their three premiers.

Charles Tupper killed that. He was not even premier when Gordon’s proposal for an intercolonial conference reached Halifax in the fall of 1863. After eight years in politics, Tupper still deferred to his party’s titular leader, his father’s old Baptist colleague, James Johnston, who had brought him into politics. The recent elections had made Johnston premier, at least in name; Tupper did not succeed him until May 1864. But Tupper’s influence on party policy was already substantial. When Gordon’s proposal came to Nova Scotia, Tupper declared that the government of Nova Scotia would not attend the conference unless delegates from the opposition went with them.

In March 1864, the Nova Scotia legislature approved a resolution by Tupper for an all-party delegation to attend the conference on Maritime union. When the premiers of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island followed Tupper’s lead, Arthur Gordon found, to his fury, that the small executive conclave he had planned had become a much larger legislative conference, and politicians from all parties would participate. Tupper had hijacked his plan, cutting out the governors and handing the conference over to the politicians Gordon despised. Gordon promptly denounced him as a man of limited ability “and considerable obstinacy.”4

From the perspective of the 1990s, Tupper’s position was riveting, for it was almost inexplicable. A premier who insisted on taking members of the opposition to a first ministers’ conference confounded everything the late twentieth century knew of politics. Through all the constitutional discussions from the Confederation of Tomorrow conference of 1967, through the Victoria conference of 1971, the patriation round of 1981-2, the Meech Lake talks of 1987-90, and the Charlottetown accord of 1992, participation was exclusively an executive prerogative. In the late twentieth century, six successive prime ministers and scores of provincial premiers preferred Arthur Gordon’s executive model to Charles Tupper’s representative one. Premiers and political analysts alike declared that to let anyone else participate in constitution-drafting would be an insult to government as it was practised in the 1990s.

Rivers of historical ink have flowed over the forces that persuaded George Brown, John A. Macdonald, and George-Étienne Cartier to sink their deep animosities and form the Canadian coalition of June 1864. By comparison, the constitutional armistice into which the politicians of the Maritime colonies entered voluntarily, shortly before their Canadian counterparts, has interested hardly anyone. Donald Creighton and his fellow historians made little of the reasons why the politicians transformed Gordon’s autocratic plan into an all-party parliamentary conference. Writing of triumphal nation-building, they had little incentive to dwell on such arcana as the proper quorum for constitutional meetings. Yet, in its way, the Maritimers’ choice to co-operate on the constitution was even more extraordinary than the Canadian coalition, since no political deadlock forced co-existence upon them.

Tupper’s sanitized memoirs are useless on this point, and the testimony of other contemporaries is not much more enlightening. D’Arcy McGee mentioned the inter-party consensus on confederation as “an extraordinary armistice in political warfare,” but did not dwell on its causes. John Hamilton Gray, who was one of New Brunswick’s delegates at Charlottetown and Quebec, said blandly that it was done to remove “the question of the union … beyond the pale of party conflict,” but he did not inquire why there should have been such a dispensation from the fierce partisanship that had long been the norm.5

The man who initiated this armistice was “Tu perds.” Charles Tupper was never magnanimous towards his rivals or gentle with those in weaker positions. His ruthlessness in the use of patronage would shock even John A. Macdonald, and he never lightly threw away the advantages of office. And Tupper’s partisanship typified mid-Victorian politics in Canada. The conservative and reform tendencies were generations old by the 1860s. Both parties understood the value of party loyalty and the uses of power and patronage. Each side had its talismans and its martyrs, and passionate hatreds had long been nursed on both sides. Tupper himself had done much to build Nova Scotia’s conservatives into a disciplined party, and he had not done it by kindness to his rivals. This sudden outbreak of bipartisan courtesy was something rare and strange.

The power of Gordon and the other governors may provide some explanation for it. After the great change of 1847, governors of British North American colonies had to accept the advice (at least on local matters) that they received from ministers chosen by elected legislatures. But in the 1860s, governors were still powerful men, not to be disdained by any politician. If they were not earls’ sons, the governors were often generals or ex-cabinet ministers. In the era when being a “gentleman” signified much more than merely polite behaviour, they were all British gentlemen, imbued with an easy, instinctive sense of natural superiority over the colonials they ruled. Even with their powers curtailed by responsible government, governors remained intimidating.

In Gordon’s small conclave of governors and premiers, the three governors, wrapped in the mantle of social precedence as well as the delegated authority of the British Crown and cabinet, would have been in the best possible position to compel consent from three over-awed colonial premiers. Invited into Gordon’s web, then, Tupper may have recruited his fellow legislators, even those from the opposition benches, as allies against the dangerous co

ercive power of the governors.

But that cannot be the whole explanation. Gordon had been right to complain of Tupper’s special obstinacy, but colonial politicians had to be able to stand up to even the most august governors if they hoped to prosper. Indeed, for the country lawyers, small-town journalists, and local merchants who won office in the Canada of the 1860s, the governors’ obligation to take advice must have been one of the pleasures of responsible government. Politicians now made policy, and some dignified baron or imperious general, fresh from the British court or cabinet room, had to dignify it with his approval and signature, no matter what his personal opinion of it or of the people who gave it to him as their “advice.” From Baldwin’s and LaFontaine’s government in the 1840s to Mackenzie King’s in the 1940s, a century of Canadian politicians loved to wrap themselves and their policies in all the pomp and prestige an aristocratic governor could provide, combining fawning deference to the viceregal office with a cold determination to ensure that it served their own will and purpose. Arthur Gordon found himself helpless – “and that helplessness felt to be a triumph over the past by the people,” as he wailed to the colonial secretary in London. Tupper could not afford to be trapped by Gordon on the union issue, but he had never been trapped before, and he had not previously needed the opposition members to save him.6

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

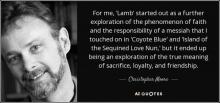

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

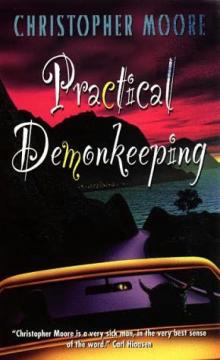

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1