- Home

- Christopher Moore

1867 Page 2

1867 Read online

Page 2

Brown talked of union, but his career had flourished amid poisonous hatreds. For all his talk of building a nation, he was a fervent southern-Ontario patriot, and the fierce pride he took in his own fast-growing, prosperous region dismayed all the other regions. He resented French-Canadian and Roman Catholic influence over the union that already existed between the future Ontario, then Canada West, and the future Quebec, then Canada East. Catholic Canada East mostly loathed him as a bigot. He talked of federation with the Maritime colonies and expansion to the West, but he hardly knew the East, and his interest in the prairie West was frankly imperial. He talked of co-operation – but he had helped provoke endless splits in his own reform coalition. With his great conservative rival, John A. Macdonald, he nursed a venomous mutual hatred. The two men had not spoken in years, unless they were hurling invective at each other in the legislature.

Brown was good at invective. He liked polemics, and he was always ready to assume he knew just what Canada West required. That kind of thing had made him a success in the newspaper business almost from the moment he founded the Globe in March 1844. Young Brown, not yet twenty-five and an immigrant newcomer when he started the paper, quickly proved himself as a publisher and as a hard-headed businessman. The Globe began as a weekly, moved to two, and then three, issues a week, and became a daily in its tenth year. Brown marketed his paper energetically, taking advantage of the new railroads to offer same-day delivery in Hamilton and London and other centres all over the province. As circulation grew, he poured money into better presses, larger premises, new wire services, and a widening network of correspondents.

It was a good time for Brown to offer himself as the tribune of Canada West, a good time for a vigorous, useful newspaper. What had been Upper Canada was putting aside the homespun days of being Montreal’s up-country frontier dependency. It was beginning to display the strengths that would make it the powerhouse of the new confederation. The population, swelled by constant immigration from Britain, was surging past a million. The farmlands were filling up. The commercial towns were prospering. Railroads now linked them to each other and to their markets.

The busy, prosperous, proud people of Canada West read the Globe for its news, its advertising, and its features – in its second year it ran a new Dickens novel as a serial – and many who abhorred Brown’s politics read the Globe for those qualities. But Brown’s Globe was above all pungently political. Its creed was the political faith Brown had absorbed and made his own in his family’s literate, well-informed, politically active milieu in Scotland. That faith was classical British constitutionalism, which rooted the liberties of Englishmen (and Scotsmen, and potentially colonials, too) in parliamentary government under the Crown. British constitutionalism had seemed backward and out-of-touch in the republican climate of New York City, where Brown and his father lived for five years after they first crossed the Atlantic in 1837. In Canada, however, such views put Brown firmly on the progressive side of the key political battles. It is difficult, at this remove, to imagine that parliamentary government could be controversial and could make Brown hated or loved or dismissed as impossible, but it is worth the effort.

The first controversial cause Brown championed in the Globe was the thing called responsible government. To state Brown’s position today is to provoke wonder as to what could have been controversial. Simply, Brown believed that politicians elected by the voters, not a governor appointed from Britain, must control the making of domestic policy. Specifically, the governor should defer in policy matters to his executive committee – the cabinet, as it was already being called. And the cabinet in turn should be selected from, and responsible to, the elected legislature. It is now hard to imagine the Canadian governor general being descended from powerful, policy-making autocrats. But in 1845 there were such governors, and the curbing of their authority was the hottest of political issues.

The British North American colonies of 1845 were emphatically not self-governing. Most men, though no women, voted, and they had been electing assemblies since 1792 in “the Canadas,” as far back as 1758 in Nova Scotia. The assemblies they elected had some real power, including powers of taxation. But the governor in each colony had powers too, including control of revenues that often left him in little need of the tax monies that only the legislature could provide.

The governor answered to Britain’s government, not to the colony’s voters. He was usually an aristocrat experienced in colonial administration or in service in the British cabinet itself, and the British government intended him to carry out its colonial policy. He also represented, at least in theory, a firm personal authority. Buttressed by the prestige of Britain and his own aristocratic standing, he could expect to be honoured as a figure worthy of respect and deference from all, immune to the factional strife of petty locals. In 1845, the governor in each British North American colony still appointed his own cabinet (it was then called his council) to run the departments of government under his direction.

This system had worked badly. For all the governor’s personal authority, his broad powers seemed arbitrary instead of dignified – and the elected assembly had enough sense of its own importance to resent the limitations upon it. So governors and assemblies fought, and in the Canadas the fight veered outside the confines of legitimate government. In 1837, rebellions against arbitrary government had exploded in both Upper and Lower Canada. When the rebellions were crushed, the governors emerged stronger than ever. When the two troublesome colonies were stuck together in the united Province of Canada, the intention was as much to buttress British authority as to yield power to either of them.

After the rebellions, however, the governors – and the British government – wanted to avoid the confrontations between assemblies and governors that had plagued the 1830s. Governors tried to find supportive assemblymen, and they sought cabinet members acceptable to the assembly. In effect, governors found themselves trying to win elective support without actually becoming bound to any party line. They proposed a compromise: they would co-operate with elected representatives without entirely yielding to them.

Many politicians and voters were ready to accept the governors’ olive branch – and the governors’ patronage, since they remained the font of honours, favours, and jobs. The governors’ commonsense request to be allowed to run administrations composed of the best-qualified men, “above mere faction,” convinced many British North Americans. It was, after all, an appeal to good will, a plea for accommodation among reasonable men who shared the goal of good government.

George Brown was among those who would have nothing to do with this half-measure. Characteristically, it was for him a matter of absolute principle. As long as the governor preserved the power to “take steps” on his own, parliamentary government was compromised. Brown would tolerate no compromise of a fundamental rule: “The executive cannot take a step without the advice of his council – his council must be chosen from the representatives of the people and have their confidence.”2 This was the nub of responsible government: an executive constantly answerable as a group to the people’s elected representatives. A cabinet would be put into office by the legislature whether the governor liked its members or not, and the cabinet would be bounced from office the moment a majority of the legislators turned against it, even if it held the governor’s confidence. Brown insisted on parliamentary government. British North Americans in their internal affairs must have all the powers of British citizens.

Indeed, Brown was more radical than the British example he constantly cited. Giving power to parliamentarians meant empowering those who elected them. In British North America as in Britain in the 1840s, property owners alone could vote. But in the colonies (unlike Britain), property ownership was widespread, and most Canadian men voted. Not only would a properly constituted Canadian government be controlled by the representatives of the people, trumpeted Brown in the Globe, but “in the election of those representatives, so low is the qualification that no man

need be without a vote if he chooses to have one.”3 Brown’s government would be not only responsible, but also representative. In the British North America of the early 1840s, Brown’s position was controversial, reformist, and democratic. He never deviated from it.* 4

In 1845, just after George Brown launched the Globe in Toronto, Governor General Lord Metcalfe, architect of the “governor-above-party” line, retired home to Britain. Metcalfe had recently helped to bring about the defeat of the reformers in a general election, but he was battered from the endless political strife. Metcalfe was also dying; facial cancer had already blinded and disfigured him. Yet, when his retirement was announced, Brown showed no sympathy. He promptly produced a special celebratory issue of the Globe. “We heartily congratulate the country on the departure of Lord Metcalfe,” he wrote.

Brown abominated the policies Metcalfe had pursued; everyone knew that. Still, the attack suggested why many would see George Brown as a political “impossibility.” His attack on the aging, sickly governor could seem not only vindictive, but also tinged with disloyalty. Metcalfe, after all, represented the natural authority of the British aristocracy, the majesty of the Queen, and all the glory of Britain and its Empire. These had no small attraction in Britain’s North American colonies. The colonies needed Britain, and loyalty meant a lot. Criticism of a governor, even when voiced in constitutional terms by a loyal Briton, still smacked of lèse-majesté.

Yet the principle championed by the reformers whom Brown supported in his paper (and would soon join in the legislature) triumphed. The Metcalfe policy, which had obliged the governor’s picked team to win every election and every legislative vote, never was feasible. In 1847, after a change in government in Britain itself, the Colonial Office accepted that its governors in British North America must appoint as their ministers whomever could command support in the elected legislature – and no one else.

No act of Parliament, no notable ceremony, marked the transition, and in the various colonies it took effect over several years. But it was momentous. Henceforth British North America’s internal affairs would be directed by politicians who could command the support of its elected legislatures. Canadian politics assumed a form still familiar at the end of the twentieth century. Lieutenant-governors and governors general suddenly became ceremonial. They would entrust the government to the leaders of the dominant party. They would appoint friends of that party to all the jobs and posts that had previously been the governor’s patronage, and they would sign into law whatever bills the governing party could get through the elected legislature.

“Under British responsible government as now in operation in Canada,” wrote George Brown a couple of years later, “the people of Canada have entire control over their public affairs.”5 Within about a decade, the British government would acknowledge that the British North American colonies had the right even to decide whether they would remain part of the British Empire. In effect, the Canadian colonies had secured sovereign authority over their own affairs. Responsible government had created the conditions under which confederation would be made and ratified less than twenty years later. All the makers of confederation were children of that moment.

Brown had been on the winning side on responsible government in the late 1840s, though he was only a fledgling journalist and held no elective office. By the 1860s, responsible government was no longer controversial. Its former opponents had adapted to the new facts of political power so successfully that they had defeated and replaced the reform ministries in several of the British North American provinces. Ironically, another of George Brown’s great principles had helped doom the reformers to minority status in the united Canadas – and had made him the voice of western alienation and anger.

George Brown believed fiercely in the separation of church and state. Not because he was irreligious or anti-religious. Brown was a devout, God-fearing Scots Presbyterian, an heir to those early Protestants who had first condemned the worldly power and worldly corruption of the Church of Rome. His “voluntaryism” – the conviction that churches should be supported by their believers, not by the state – was deeply rooted in his family. An invitation to his father to edit a Toronto Presbyterian newspaper “on the voluntary principle” had helped bring the Browns to Canada. As true Scots Presbyterians, the Browns would have no bishops, no popes, and no elaborate worldly institutions standing between a man and his God.

Today, separation of church and state seems as much a political platitude as responsible government. Even in the 1860s, church and state were separate; there were no longer any “established” churches in the colonies. But it was an age of faith, and everywhere religion impinged on politics. The split between tories and reformers over responsible government could still be found mirrored in tension between high-church Anglicans and evangelical-minded dissenters like the Presbyterians. It was Catholics, however, not Protestants, who felt most threatened by the voluntaryism that was part of George Brown’s religion and his politics. And in the union of the Canadas, what threatened Catholics threatened the union itself, for Canada East was as staunchly Catholic as Canada West was Protestant.

As a Scotsman, a Briton, and a Protestant, Brown had been brought up to cherish deep suspicions of the Roman Catholic Church. Any Presbyterian minister could thunder for hours about the Church of Rome’s worldly pomp, its idolatry, its support for superstition and ignorance, and its malevolent efforts to inject popish power into civil society. The historical pageant of British liberty and parliamentary government, which Brown loved and sought to extend to British North America, was also a story of English resistance to the pope, to absolutist and Catholic powers in Spain and France, and to the Catholic Stuarts, who had been deposed from the English throne in 1688. Brown could not help but look with scepticism and alarm at the Catholic Church, wherever it was found. And in British North America, Catholicism was as fundamental as the French language to the identity of the majority population of Canada East.

Brown respected the right of all people to worship as they pleased. Individual liberties and freedom of conscience were touchstones of his politics, amply demonstrated in his support of anti-slavery movements and of American slaves who had escaped to Upper Canada. He believed in economic freedom too: freedom of trade, freedom of contract, unfettered competition of the kind the Globe had with many rival newspapers. But the kind of religious freedom Brown ringingly defended was not the kind most Roman Catholics wanted.

In the 1850s, the Catholic Church was on the move. In Lower Canada, dynamic bishops, supported by energetic priests from newly founded seminaries, had shored up the church’s institutions and extended its moral influence. The church no longer needed to curry the support or tolerance of powerful governors. As political power shifted from royal governors to elected parliamentarians, bishops and priests could influence Catholic voters directly, and they did so openly and willingly. Few politicians seeking election in Catholic communities cared to provoke the disapproval of the church.

The church’s social role and political power were most evident in francophone Lower Canada. But as Irish Catholics poured into Upper Canada, the church was eager to acquire the same place there for its bishops, its separate schools, and its social message. No admirer of the church’s social and political sway in Lower Canada, George Brown was all the more alarmed to sense Catholicism on the march in Upper Canada.

Brown’s opposition to separate schools, to the extension of Catholic dioceses, to the political influence of priests and bishops – to what he called “priestcraft and statechurchism” – all flowed from his voluntaryist principles. And they tended to alienate every Catholic who heard them. It made little difference to faithful Catholics whether Brown was in his heart a principled voluntaryist or simply an anti-Catholic fanatic. They understood he was no friend to them or to their religion as it was practised.

Whether voluntaryism or bigotry, Brown’s campaign to separate church from state was no friend to his own political ambitions eit

her. In the union of Canada East and Canada West, where the East was heavily Catholic and the West mostly Protestant, anything that raised Catholic–Protestant tensions was hotly political. Catholic legislators wanted nothing to do with Brown, and voluntaryism as Brown espoused it played a vital role in keeping his reform cause out of power for a generation. Voluntaryism cemented his reputation as an anti-French politician at a time when the first requirement for political success was the building of French–English alliances.

Britain had forged the Province of Canada in 1841 amidst ringing declarations that its purpose was to absorb and assimilate French Canada into a properly British colony. In renaming Lower and Upper Canada as Canada East and Canada West and fusing them together under a single parliament, the Colonial Office hoped to see the anglophone majority take firm control. It did not happen. Under responsible government, the provincial Parliament became the forum in which the political power of the francophone minority of what is now Canada was permanently established. In retrospect, the reason seemed obvious to anyone who could count votes: Canada East had half the seats in the assembly of the new union, and most of those depended on francophone votes. Minority status encouraged the francophones, much more than their anglophone neighbours, to vote as a cohesive bloc. As a result, Canada East was never much more than one vote away from a working majority.

As soon as the union of the Canadas was formed in 1841, reform strategists in Canada West grasped that an alliance with Canada East was their sure and only route to power, and the man they had to talk to was Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine. LaFontaine had seen in the assembly a forum in which to defend the French-Canadian community – if the assembly achieved its potential through responsible government. On that basis, he secured massive support from the francophone electorate for the policy of responsible government. In the 1840s, responsible government produced an alliance between Catholic francophones (otherwise suspicious of English Protestant power) and Protestant anglophones (otherwise rather anti-Catholic and anti-French). That alliance put the reformers in power in 1848, under the joint leadership of LaFontaine and his partner from Canada West, Robert Baldwin.

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

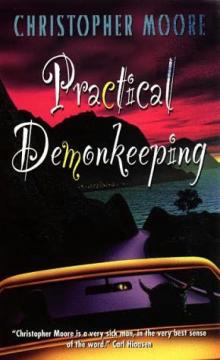

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1