- Home

- Christopher Moore

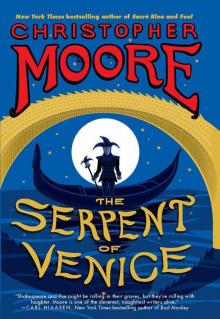

The Serpent of Venice Page 8

The Serpent of Venice Read online

Page 8

“No, what we learn is, do not fuck with Moses!” He patted my arm. “Come.”

I found that suddenly I quite liked the old Jew. I felt bad at the suffering that was about to befall him, even, perhaps, by my hand. By keeping it to myself, was I turning on my tribe?

A handsome young merchant wearing a purple cravat hailed Shylock, waved him to come into an archway where a group of men were gathered.

“Bassanio,” said Shylock. “He came to me as an agent for Antonio, who would borrow money. You know this Antonio, Lancelot?”

“I know of him.”

“Ah. Yes. Know this. I do hate him with all my being and I would have him undone. Does this shock you?”

“No, signor,” said I. “I am sure he has given you reason for your ire.” Having somewhat to do with his being a massive festering twat! I hastened to not add, lest I reveal my own substantial prejudice. Still, it appeared that Shylock and I were, indeed, brothers in arms, even if he did not know it.

We followed Bassanio into the arch, where Antonio held court with a group of young men. All seemed too tall or too light of hair to be Jessica’s Lorenzo. The merchant was dressed in higher finery than his companions, silks and damask—higher finery, I thought, than appropriate when about to ask an enemy for a loan. I kept my eyes to the ground, my hat covering most of my face. If discovered, I could make no escape on the chopines, and I’d never be out of them in time to elude Antonio’s entourage, but by God’s cloud-cushioned balls, I would slash the fish knife across the inside of Antonio’s thigh before I went down, and he would watch his fine hosiery spoilt as his life ran between the pavers in red rivulets. But there were three men to undo, three on whom to wreak revenge, so better the knife stay nested in its sheath of rags in Jessica’s boot, which I wore as well. (Yes, I have small feet. The rest is myth. No one finds you clever.)

“Antonio,” said Shylock, with a nod. “You do not borrow. I heard you say it when you denounced my business.”

“I never do, Shylock, for myself. But I break custom to supply the ripe wants of my friend. Did he tell you the amount?”

“Aye, three thousand ducats.”

“For three months,” marked Antonio.

“Yes, yes, for three months. I had forgotten. But word is on the Rialto that all of your fortunes are at sea. You have an argosy bound for Spain, another in the Black Sea, and a third bound for Egypt. All subject to the temper of the sea and attacks from Genoans and pirates. I should bear your risk without reward? Yet you have called my charging interest evil.”

“Charge what you will. My ships and fortunes shall all be returned within two months, a month before my bond is forfeited.”

“Three thousand ducats; tis a good round sum,” said Shylock, stroking his beard in thought.

“Tis a sick elephant’s shitload,” I whispered. “Are you daft?”

“Shhhhhh, boy,” said Shylock.

“Sorry,” said I. They’d all looked to me when I spoke, even Antonio, and there was no spark of recognition in his eye, nor did he see the fire in mine. His gaze stopped at the shore of my outfit and “Jew” was all he saw. Unworthy of a second look. I began to fancy my yellow hat.

Shylock said, “Signor Antonio, many a time in the Rialto you have berated me about my moneys and my usances. Still, have I born it with a patient shrug, for sufferance is the badge of all our tribe. You call me misbeliever and cutthroat dog, and spit upon my Jewish gabardine, and all because I use what is mine own.”

Shylock threw his arms out as if receiving a revelation and continued, “Well now—now it appears you need my help. You say, ‘Shylock, we would have moneys.’ You say this. You, that did spit upon my beard and kick me as you might kick a stray dog in your threshold. What should I say to you? Should I not say, ‘Hath a dog money? Is it possible a cur can lend three thousand ducats?’

“Or should I bend my knee, and with the bated breath of a slave, say to you, ‘Oh, fair sir, you spit on me Wednesday last. You spurned me another day. Another you call me dog, and for these courtesies, allow me to lend you moneys?’ Should this I say?”

Antonio had been backed against the wall as Shylock spoke, as if the old Jew was pissing on his shoes the whole time he spoke and the merchant avoiding the stream. Now he came forward.

“And I am likely to call thee dog again, to spit on thee again, to spurn thee again. If you will lend this money, lend it not as a friend, but to an enemy, and should I break my bond, take relish in exacting your penalty.”

Shylock smiled and waved his hand as if dismissing the whole exchange, even as if Antonio’s anger was a gnat born of imagination. “Listen to you, how you storm. I would be your friend, good Antonio.” Another smile, as if the hatred hurled between them had been but a vapor. I relaxed in my own anger for a moment, for it was apparent, even if only to me, that Shylock was the master of this deal. “I will loan you your three thousand ducats, for three months, and take no interest for my moneys, and you may say that I have forgiven your offenses and shown you kindness.”

“There is kindness in his offer,” said Bassanio.

“Yes,” said Shylock. “Now, go with me to a notary and there seal your bond. My servant has my papers here. And for merry sport, to mark our friendship, if you do not repay me on a certain day, let us say that you shall forfeit—”

“His Johnson!” said I, somewhat surprised I had spoken.

“A moment,” said Shylock, holding up a finger to mark his place. “I would have words with my servant.” He put his arm around me and walked me away.

“Are you mad?” whispered Shylock.

“Saw off his knob with a dull knife while he screams for mercy,” said I, rather more loudly than Shylock’s conspiratorial tone suggested was appropriate. This bit was not so surprising to me, but in for a penny . . .

“You, boy, will be silent and carry my papers and let me do my business.”

“But—”

“I know you are not who you say you are,” whispered Shylock. “Would you have me tell them?”

“Proceed,” said I, bowing and waving him back into the fray.

“Ha!” said Shylock, returning. “The boy can be simple. I employ him as a kindness to his poor blind father. Now, Antonio, as I was saying, my moneys, with no interest, for three months, but as a jest, should you not repay me upon the date, let us say that I, take, uh—” Shylock again spooled his hand as if trying to reel in an idea floating above. “A pound of flesh, cut from your body, from a place of my choosing.” The smile.

Antonio laughed, threw his head back. “Yes! I’ll seal such a bond, and say there is much kindness in the Jew.”

“No!” said Bassanio. “You shall not seal such a bond for me. I’d rather do without the lady.”

“Fear not, my good friend.” Antonio squeezed Bassanio’s shoulder and his hand lingered there as he whispered, but loudly enough for us all to hear. “I will repay the debt a month before the bond is due and we shall all have a good laugh at the Jew’s frivolity.”

“Yes, boy,” said Shylock. “What value is a man’s flesh to me? Surely not that of a beef, or goat, or mutton. There is no profit in this for me, but only a gesture of good faith from Antonio. How say you, good Antonio?”

“Yes, Shylock, I will seal unto this bond. Lead on.”

Shylock grinned, then quickly assumed his visage of serious business and trudged away, Antonio behind him. The entourage moved away from the wall in turn and I fell in beside the tallest.

“Tell me, friend. Is one of you gentlemen called Lorenzo?”

“No, Jew, but Lorenzo is a friend of ours. Why do you seek him?”

“I have a message for him.”

“We are meeting him tonight at Signora Veronica’s. You can tell me.”

“Oh no, I couldn’t,” said I. “I must give the message only to Lorenzo in person.”

“I am Gratiano, close friend of Lorenzo. Ask anyone, they will tell you that we are as brothers.”

“I cannot,” said I.

>

Gratiano bent in closely and whispered, “I know about Lorenzo and the Jew’s daughter.”

I nearly stumbled and fell off my chopines. “Fuckstockings, can no one keep a bloody secret in this steaming piss pot of a city?”

Jessica was not going to be at all pleased with her new slave.

*This actually happened in York in 1190.

†Clueless.

‡Great Britain.

NINE

Two Thousand Nine Hundred and Ninety-nine Golden Ducats

I followed Shylock down walkways along narrow canals to the landing at St. Mark’s Square, where we would catch a ferry home, across the tronchetto. Since we’d left the notary with Antonio’s signed bond, Shylock had not said a word about knowing who I was. I was carrying a small cask of wine, and although it was not terribly heavy, keeping balanced on Jessica’s platforms was some challenge.

“So,” said I. “Just chopping random bits off a bloke, something you Jews do a lot then?”

“It was your idea to take his manhood, Lancelot Gobbo. No man would agree to such a bargain. An arm, a leg, a random pound of flesh, yes. I merely made salvage of your folly. I am surprised that Antonio would put his bond to it. His need exceeds appearances.”

“Why does he need to borrow funds from you? He said it is for his friend?”

“For the young man Bassanio, who proposed such a loan to me on the Rialto this morning. He says he would use it as a bride price for the lady Portia of Belmont, and Antonio staked him to it. I do not care about Antonio’s reasons, only that they have put me at advantage over him.”

“Portia? Brabantio’s daughter Portia? Brabantio is one of the richest senators in Venice, and Antonio is his partner in most heinous ventures. He would give him three thousand ducats for the asking?”

“You have not heard, then? The Montressor is dead.”

I meant to inquire when? How? But Shylock held his finger to his lips to signal silence. We had reached the ferry, which was fitted out to carry narrow handcarts across the channel. It was clear that Shylock did not know the ferryman as he had the gondolier from earlier, whom we were spurning by walking in the heat and taking this shit flat boat.

As we crossed the wide green channel, I looked for the dark shadow I had seen beneath the water before, but there were only little silver fishes, wetly doing fish things near the surface.

Shylock did not speak again until we were across the channel and in the narrow alley that would take us to the seaside of La Giudecca.

“So, what is your grudge with Antonio, little one?”

“Little one? I’m taller than you are.”

“I saw you were wearing Jessica’s boots and platforms when we were crossing in the gondola.”

“Well, this is a rubbish disguise.” I balanced the cask on my shoulder with one hand and ripped off my stupid yellow hat with my other and cast it to the ground.

Shylock put down his box of papers and quills, picked up my hat and fitted it back on my head, then picked up his box and stood there, blocking the alley, which was only a bit wider than a man’s shoulders. He raised a grizzled eyebrow at me. “What is your grudge with Antonio?”

“No,” said I. “What is your grudge with Antonio, and how do you think it will be settled by giving him three thousand ducats?”

“I am your employer, and I did not reveal you to Antonio and his friends,” said Shylock.

“Well, I have your wine and your daughter’s shoes.”

“I am a man of means and can buy more wine and shoes, but if you do not tell me, you will have no place to sleep tonight and no food to eat.”

“Well, I’ll have a bloody hogshead of wine to myself,” said I.

“Fine, as the tailor said to the broke and naked knight, suit yourself.” He turned and strode off down the alley.

Is that where that saying comes from? Seems I should have known that. Shylock receded down the alley. As he was about to go around the corner I blurted, “He killed my wife and he tried to kill me—left me chained in a dungeon to die. He does not know I survived.”

Shylock looked over his shoulder. “Antonio did this?”

“He and two others.”

Shylock nodded. “Come. Bring my wine.”

“Now you.”

“We don’t call it a hogshead,” said Shylock.

“What does it matter?”

“A Jew would not call it a hogshead. Mind your disguise.”

“Why do you risk your ducats?”

“They are not my ducats. My friend Tubal will supply the loan.”

“But to the point, your grudge with Antonio?”

“If I tell you that Antonio has earned my hatred, would you be satisfied?”

“It strains not my imagination that Antonio earns your hate, but for three thousand ducats you could hire a choir of cutthroats to remove him.”

“Antonio hates me for my ancient faith, yet his pope makes wars to take Jerusalem from the Saracens. He makes profit on these holy wars, yet calls my thrift a sin. He mocks me for my interest, yet the law forbids me from owning property on which to collect rents. He laughs at me that I must pay to be ferried to and from the Rialto, because the law allows my people to live only on this island. He berates me for this yellow hat I must wear, because the law of his city dictates it. His city, Venice, that makes nothing, grows nothing but salt, does no other thing than trade, and is said to be the glory of the world because her laws treat all fairly. His Venice that has no king, has no lords, but is a republic, a city of laws, a city of the people, says he. A city built on justice, says he! Well, I will have my justice by way of the law. I will see Antonio’s Venice condemn him, sentence him to pour his blood into the canals for his beloved laws. I would have my revenge by way of this so-just law.”

Shylock’s shoulders were heaving with breath, with his anger. I had been pummeled by the blundering angels of false justice as both slave and sovereign; I knew his fire.

“There is risk,” said I. “What if he repays you in good time?”

“If any one of his three ships runs afoul, his fate is mine, and I will weigh his flesh on those same scales that Venice says do stand for justice. God will see to it.”

“Well, I wouldn’t wager a jolly jar of Jew toss for the God nonsense, but I’m in for three-to-one odds of undoing Antonio.”

“Then you will not interfere with my plan?”

“Your revenge shall be my revenge,” said I. Unless it fails, then I will sculpt my own mayhem for Antonio, I thought.

“Then home, and we shall drink to it,” said Shylock. “But no word of this in front of Jessica. She is of a sweet and delicate disposition; I would not have her poisoned by her father’s hateful strategies.”

“Jessica pulled me from the sea—saved me,” said I. “A right love, is your Jessica. If up to me, she shall never hear so much as the whisper of an unkind word.”

But she would, she had, and I, undrowned for only days, was torn now by opposing loyalties.

“You scheming duplicitous harpy, why didn’t you tell me?” said I to the gentle Jessica. “Your father says Brabantio was eaten by rats?”

“You didn’t ask, oh troubadour who was shipwrecked on the way to England and therefore would have no interest in the politics of Venice.” She sang the last bit, just to be annoying.

Shylock had gone to Tubal’s house to assure that he could secure the ducats for Antonio’s loan, leaving Jessica and me alone in the house.

“Making a point will not return you to my good graces.” I could have crushed her paltry argument if I revealed that I knew the contents of her note to Lorenzo, although that would have somewhat undermined my own trustworthiness.

“You are the one who didn’t do his job, slave.”

“Lorenzo was not with Antonio. Would you have had me give your note to another of Antonio’s scoundrels and hope he delivered it to your beloved? Gratiano wanted it, that egregious weasel—may as well give it to old blind Gobbo and have him

orbit the island with it for eternity.”

“Well, you must go back, then. Tonight. Papa and Tubal are sending a chest with the ducats to Antonio this evening. You will go with them and deliver my note to Lorenzo then. And wait for a reply.”

“I will,” said I, head bowed. And I would. And from there go to my old apartments to inquire after my monkey, Jeff, and my apprentice, Drool. I can’t imagine the great ninny making do on his own for a month. True, he had nothing of value except for his great size and a preternatural gift for mimicry, but fate does not favor the dim, and I worried about him wandering around unprotected in a city whose streets were filled with water. He swims like a stone.

“Tell me, now,” said I. “What do you know of this favor Antonio does for his friend Bassanio that would require he risk his very life for a loan? Do you know of it?”

“Oh, yes, Lorenzo told me of it. Bragged to his friends that he was so clever as to capture his lady love without risking his fortune like Bassanio. You know of the contest for Portia’s hand and estate?”

“Contest?”

She explained the bizarre lottery Brabantio had left his younger daughter to be prize for: three caskets, sealed with wax and watched over by lawyers, three thousand ducats for the mere chance at the lady’s hand. Oh, Othello, what a bitter mess you made of Brabantio when you married Desdemona. I thought that my murder was the limit of Brabantio’s hatred for Othello, but apparently he was reaching out from the grave to torment his younger daughter as punishment to the elder.

Shylock had not known the circumstances preceding Brabantio having been eaten by rats. Perhaps his heart gave out while he was carrying away his bucket of mortar. The scream that night—I had some hope that his last thoughts might have been of me. Now, with my terror tamed, seems ’twas a sweet scream indeed, although not nearly long enough. But now, to have Brabantio’s hatred spill out onto Antonio, well, perhaps the Fates were turning to favor a fool . . .

The Greeks believe the Fates are three sisters: one is Order, who spins out the linear thread of a life from the beginning; another is Irony, who gently cocks up the thread, marking it with some peculiar sense of balance, like justice, only blind drunk with a scale that’s been bunged into the street so it never quite settles; and the third, Inevitability, simply sits in the corner taking notes and criticizing the other two for being shameless slags until she cuts life’s thread, leaving everyone miffed at the timing. It seems to me that a nimble fool, possessed of a quick wit and passionate provocation, might have two sisters at once, and thus bring the third in to serve her purpose on his enemies as well. I would find my way to be fate’s tool.

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1