- Home

- Christopher Moore

Shakespeare for Squirrels Page 4

Shakespeare for Squirrels Read online

Page 4

And thus I trudged through fern and forest for hours before I heard weeping in the distance, another lost soul, perhaps, who had met her mortality. Whence it came I could not say, for the woods had gone batshaggingly dark, and while the full moon cast a tattered lace of silver through the canopy, it was only enough light to allow a lonesome fool a few quick steps before running into the next tree trunk. I followed the sound, however, for as the eye was deprived, the forest served the ear a feast of menacing sounds, most made by scurrying creatures that wished me harm.

There, ahead, in a pool of moonlight, on a large rock, sat a rather tall young woman. Her hair was dark, pinned up, her dress white and light as summer, high necked, the collar and cuffs embroidered with small pink roses. She hugged herself and rocked, as if each heartbreaking sob wrenched out a bit of her soul, then she refilled her bellows in broken gasps with the world’s sorrow. The sound brought tears to my eyes and I would have embraced the poor creature, offered her comfort, had I been more than a spirit lost in the wood. Instead, weary, I sat down on the stone beside her.

She shrieked, high, shrill, and girlish, and jumped to her feet.

I shrieked, high, loud, and somewhat less girlish, and jumped to mine.

She wheeled on me, angry, her eyes still wet with tears. “Thou knave! Thou sneak! Back, villain!”

“You can see me?” said I.

“Of course I can bloody see you, despite your creeping up on me like some lurker in the dark!”

“I did not creep. I am a ghost, invisible to all but the magical forest people.”

“Well I can see you, and I’m not a bloody forest person.” She wiped her eyes and stepped back from me, looked me over in an overly personal way, as if trying to spot a burr snagged in my motley. “Say,” said she, “you used to be a monkey, didn’t you?”

“I did not. I was a fool. A charming, clever fool.”

“Well earlier there was a monkey dressed in that same fool’s outfit. Had his way with my hat and ran off. I’ve heard all manner of magical things happen in this wood. It would just be fitting that the only man who would deign to talk to me is a hat-shagging monkey.” She leaned in closely. “You, sir, have the look of a hat shagger.”

“I do not. But I know a monkey who is quite fond of hats. Called Jeff.”

“Good you specified,” said the puppet Jones. “Lest we blame some other monkey dressed in black and silver jester togs.”

“Quiet,” I told the puppet. Jeff? Alive? Why, I had barely had time to miss him.

“I’ll have my hat back now,” said the girl. “Or have you used it and cast it aside, too? You men are monsters, even those of you who used to be monkeys.”

“I am neither a monster nor a monkey, I am but a sullen newborn ghost, and I only stopped because I heard you weeping and thought I might help.”

“You may help, if you can lead me out of this sodding forest.”

“Me? I was going to ask you. Is this not your country? How is it that you find yourself lost in the forest of your own familiarity?”

“I followed my love, my handsome Demetrius, into the forest.”

“And he was eaten by a bear?”

“No, that’s horrible. Why would you say such a thing?”

“He’s not here, is he? And there you are, sobbing like you’ve been dirked in the dick by grief’s dark dagger. Ergo. Ursa. Arborem. Therefore, bear in the forest.”

“That means ‘bear in a tree,’ fool. And there was no sodding bear. Demetrius has run off after my used-to-be-friend Hermia, who is petite and beautiful, fair of hair, and sweet of voice. If you saw her you would love her too. All men do.”

“I would not. I am soured on love. Also, deceased.”

“Oh, you would dote upon her, make great cow eyes at her, and sing her your songs of woo.”

“I would not. I do not make cow eyes, nor do I moo woo.”

“You would. Just like Demetrius. Oh, he wooed me. Promised me future and family, but when Hermia’s father showed him favor, he forgot me and had only eyes for her and her fortune. She does not love him. She loves Lysander, a boy she has loved since school, but her father detests Lysander, and so commanded her to marry Demetrius on pain of death. The duke backed him but would condemn her to life as a nun, forever without the company of men. So she and Lysander ran off together to live under protection of Lysander’s maiden aunt. I told Demetrius of their plans, thinking he would forget her and love me again, but he did not. He ran after them.”

“And you after him?”

“Well, obviously. But he pushed me down and ran off, faster than I could follow. Skirts are shit for running in the woods.” She waved to the skirt of her long white gown, the hem was stained green and brown, snagged with nettles and foxtails.

“Forget this Demetrius, he sounds to be an opportunist fuckweasel,” said I with a wave of dismissal I reserve for such creatures. “Look at you . . . What is your name?”

“Helena.”

“Look at you, Helena, you are fairly fit and probably not entirely unpleasant when you are not shouting. You can do better.”

“But Demetrius has touched my soul and fired my heart.”

“Has anyone else touched your soul? I mean, if you’ve only had one soul-touch you might not be as on fire as you think. You might just need a raucous, all-night drunken soul-touching that leaves you a puddle of soggy embers in the morning. Then you’ll forget all about him.” I bounced my eyebrows at the prospect, then winced, as the bruise on my forehead was still tender and bright. I swooned a bit with the pain and sat again upon the rock.

“No,” said Helena, sitting down beside me. “I shall become a nun, and forever eschew the company of men. Loneliness shall be my lot, and I shall dwell in quiet contemplation of my misery.” And she began to weep again.

“Cheer up, lass,” said the puppet Jones. “You’ll probably starve to death in the forest first.”

“Shut up, Jones!” said I.

“Or be eaten by elves . . . ,” the puppet added.

“Oh woe!” the girl cried, and buried her face in my shoulder.

I wrapped a tentative arm around her shoulders. “I know, lamb, love is a besquished toad ripening in the sun. But despair not, life in the nunnery is not completely devoid of joy. I was raised by nuns. Once a week you’ll be able to share a sumptuous raisin with your sisters, and then there’s the perpetual flicking of the bean in the dark, for which you’ll have ongoing guilt and repentance during the day, so you’ll stay busy.”

“But I don’t want to be a nun, I want to go home. Take me home, fool, please. It’s dark, and you know what happens when it gets dark in the forest?”

I had spent more than a few nights in the forests of Britain in my youth and I remembered little to fear in the forest dark beyond the cold and damp, which, to be fair, was often the case any place or time in Old Blighty. “Supper?” I ventured hopefully.

“Not supper! Creatures of the dark! Evil ravening creatures that rend the flesh from your bones and eat it while you watch. Some say it’s the forest people themselves, transformed into night beasts. They are demons, sir. No one who has seen them has lived to tell the tale.” She flinched, startled by a noise in the bushes. She dug her nails into my arm and pulled me tight, as if to use me as a shield against the stirring. “Alas, it is too late. They are upon us.”

“Unhand her, you rogue,” said a male voice from the bushes, and then an entirely unremarkable yellow-haired bloke stepped out of the bushes. He was dressed in a belted jerkin, leggings, and tall boots, so not at all how I had been led to believe proper Greeks dressed from the vases I’d seen, which was a nappy and a sword.

“Demetrius!” said Helena. She moved to rise but I held her fast.

“Oh, that scoundrel,” said I. “Shall I purple up his eyes, milady? Shall I relieve him of his teeth so he may send his stuttered lies through broken bleeding lips? Give the command, milady.”

“You can’t say that,” said Demetrius. “S

he is . . . I am . . . You are . . . Helena followed me into the forest.”

“And you did not want her. Used her. Spurned her. Pushed her down and ran after another.”

“Well, yes, but I don’t want anyone else to have her.”

“And you have come back to me,” said Helena. She stood and rushed to him, her arms wide to receive his embrace. He stepped aside and she tumbled headlong into the shrubbery.

“I’m lost,” said Demetrius. “I heard voices and ended up here.”

Helena climbed out of the bushes. Her hair had shed some of its pins and hung in tendrils in her face. She spat out a leaf. “And you returned to rescue me,” she said with entirely too much hope.

“I was hoping someone would know the way back to town,” said Demetrius, ignoring the girl.

“You don’t know the way to Athens and you’re not wearing your nappy and sword. You are a shit Greek, Demetrius.”

“Sir, count yourself lucky that I have left my bow and sword at home, for on my honor, if I were armed, I would make you pay for your words.”

“A shit Greek, I say. Everyone knows that you always go about with a sword, maybe even a shield if you’re out walking your three-headed dog.” I have read the classics. “I, too, am unarmed, but just as well, that I might box your ears until you beg for mercy, then slay you later at my own convenience.”

Of course I lied about being unarmed. I’m not mad, the Greek was a foot taller than I, two stone heavier, and had probably eaten more than a handful of nuts and berries over the last week.

“Lay on, thou piss-haired spunk-whistle!” I should probably have stood up at that point, but truth be told, I was feeling weak and thought if I stood up quickly I might faint.

The Greek looked confused. He had stumbled into a fight he did not want over a girl he did not fancy, and even in the moonlight I could see his eyes darting around in search of an exit like flies buzzing in a jar. And an exit was granted, as from the other side of the clearing a great roar sounded out of the bushes, and a figure rose tall in the darkness, thrashing in the undergrowth as it charged.

“Bear!” cried the puppet Jones.

“Did that puppet just talk?” asked Demetrius.

“Run,” said Helena, grabbing Demetrius’s hand and dragging him off into the forest, both of their voices rising in high terror as they went.

I stood, then, and reached into the small of my back for a dagger, which I drew and held before me, but I swooned and fell back onto my bottom on the rock. “Oh balls,” said I as the moonlight-laced clearing began to spin. As I dropped my dagger and as I sank into the darkness I heard high, happy giggling.

“Haw, haw,” sang Cobweb. “They thought I was a bear!” She danced a jig before me, hopping from foot to foot, as if some piper were trilling a shanty only she could hear. “Haw, haw. Cobweb the scary bear. Did I scare you?”

I shook my head, more to clear the haze in my vision than as an answer. “Most excellent bear, Cobweb. And well done on the timing, as well.”

She giggled, clapped, and hopped, delighted with herself. “I saw you was going to fight that straw-haired bloke and you didn’t look up to the task.”

“Well, I was murdered at lunchtime, so I’m not at my best.”

“Where’s your big friend?” She picked up my dagger and handed it to me. When she bent before me I got a good look at her right ear, which tapered to a gentle point, like the Puck’s. So.

“Taken by the watch,” I said, sheathing the dagger. “And the blackguard captain who killed me. I reckon I am doomed to walk among the living until I rescue the great ninny, and only then will I find eternal rest.”

Cobweb tilted her head as if examining a spot between my eyes, like a cat might consider a dragonfly before dashing it to bits with a quick claw. “You’re daft and you stink of rotting fish. You didn’t wash your clothes in the stream like I told you, did you?”

“It was on the agenda, but then I was murdered.”

“No you weren’t. Now shed your shabby husks and I’ll give them a slosh while you eat.” She turned and marched to the edge of the clearing.

My stomach lurched at the mention of eating. “Where are you going?”

“To build you a nest to lie in so you don’t fall against the rock and dash out what’s left of your brains. Now off with your kit, fool.”

“I’m fine,” I said, standing up to show I was, but stumbled a bit to catch my balance. “Bit dead, but for a ghost, fine.”

“Pocket!” she said, using my name for the first time, wheeling on a heel. She strode back across the clearing and stepped up to me until her nose near touched my chin. “You are not dead. You may be a bloody loon, but you are not dead.”

“I am. Slain this very day by Blacktooth.”

“Are you hungry?” she inquired, stepping again so close she might have rung the bells on my toes if the pirates had not stolen them.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Are you thirsty?”

“Well, yes.”

“Does this hurt?” And at that she viciously pinched and twisted my starboard nipple.

“Ouch!” I pushed her away, resisting the urge to return a twist of the tit, as I am a fucking gentleman. “That is no proof—”

“Does it hurt?” she snapped.

“Yes! Yes it hurts, thou venomous mouse.”

“Then you’re not bloody dead, are you?”

I rubbed my offended man-pap and considered her thesis. The eternal sleep did seem rather uncomfortable, itchy even, although not so much as to constitute hellish torment. “Well, I was dead. Blacktooth and the guard could not see me, even as I passed not an arm’s length before them. Explain that.”

“Trickery,” said the puppet Jones. “Or more likely you’re bloody barking and you imagined the whole thing.”

“That’s quite clever,” said Cobweb, looking at Jones, who leaned against the stone. “I didn’t even see your mouth move.”

“I didn’t do it. Since I died this wooden-headed ninny has been babbling away on his own.”

“Then I’d have to agree with him,” said Cobweb. “You’re barking.”

She skipped to the edge of the clearing, where she began collecting leaves and branches and arranging them in a circle with practiced alacrity. She gamboled in the forest like a purposeful butterfly, barely stirring a stem or making a sound. In no time she had constructed a nest of soft ferns with pine boughs woven over it. “Here you go,” she said, patting a bed of silvery leaves. “Hop in and get your kit off. I’ll fetch some nuts and berries.”

I thought to argue, but it was an excellent nest, so I climbed defiantly under the entry boughs, plopped down, and removed my boots without another word. Cobweb was laying a fire not six feet away from the nest. I got a good glimpse of her ears again as she struck steel on flint. I rolled up one of my stockings and tossed it so it passed in front of her.

“What’s that?” she said, looking at me as if I might be daft.

“Nothing,” said I. “Thought you wanted my clothes. For washing.”

“Right,” she said.

I rolled up the other stocking and tossed it by her.

“No elves,” she said, without looking from her labors.

“Sorry?”

“There are no bloody elves here, so stop throwing your socks at me.”

“‘The stockings of the dead run far,’ we say in England.” I stripped off the rest of my kit and handed it through the arch of branches, keeping my sheath of daggers in my lap to cover my man bits, and I settled into the nest. The leaves lining the floor were as soft as lambs’ ears against my bare bottom.

“I’ll wager no one in England or anywhere else has ever said that. And you’re not bloody dead. Do I have to prove that again?” She made a pincher movement with her fingers and grinned malevolently.

“Translated from the French,” I added for flavor. “Smashing nest though.”

“They’re usually built up a tree, out of reach of bear

s, but I can’t have you falling on your head again, can I?” She gathered my kit into a bundle.

“Bears?” I inquired.

“I’m off to wash these and gather some food.” She unslung a water skin from her shoulder and tossed it into the nest. Drool had been arrested with the previous one she’d given me. “Do try not to be eaten while I’m gone.”

“Bears?” I inquired further.

“No, the fire will keep bears away.” And with that she was gone into the night.

“Bloody elfs,” said the puppet Jones.

I sat, I drank water, and being again among the quick, I had a wee at the edge of the firelight and contemplated my resurrection and responsibility. At some point I curled into a ball on the leaves and dozed off.

* * *

I awoke to a wet whisper in my ear and a warm body pressed to my back.

“There’s food, when it suits you,” she said.

I moaned, stubborn to stay drifting among my dreams. “In the morning,” I said.

She snuggled against me, her fingertips danced over my brow, down my back, over my ribs, as soft as a sigh. I felt I might melt into the touch, so long had it been since I’d been touched without anger or utility. A delicate hand slid over my hip and down over my manhood.

I rolled away, wide awake. Her eyes were black with orange specters in the dim firelight, surprised but not alarmed. “Friends?” she said, with a bit of a pout.

“Knackered,” I replied. “Perhaps just a cuddle, for warmth. And put your frock back on, love. A fresh young thing like yourself, defenseless before my wisdom and charm, well, I would not take advantage, it would be unseemly.”

“I am nine hundred years old, sprout.”

“You are not.”

“I am.”

“Elf!” cried the puppet Jones.

“You said there were no elves here,” said I.

“There are no elves,” she said.

“Liar!” said the puppet Jones.

“Fuckload of fairies,” she said, “but no elves.”

“You’re a fairy?”

“Aye, since the blossom first opened to reveal me curled inside it.”

“A fucking fairy?”

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

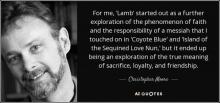

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

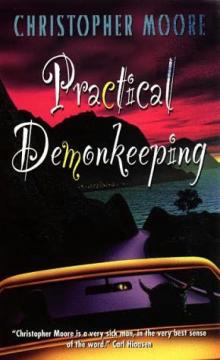

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1