- Home

- Christopher Moore

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 Page 4

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 Read online

Page 4

“Let me worry about that. I’m quadrupling my sessions. I want to see these people get better, not mask their problems.”

“This is about Bess Leander’s suicide, isn’t it?”

“I’m not going to lose another one, Winston.”

“Antidepressants don’t increase the incidence of suicide or violence. Eli Lilly proved that in court.”

“Yes and O.J. walked. Court is one thing, Winston, the reality of losing a patient is another. I’m taking charge of my practice. Now order the pills. I’m sure the profit margin is going to be quite a bit higher on sugar pills than it is on Prozac.”

“I could go to the Florida Keys. There’s a place down there where they let you swim with bottlenose dolphins.”

“You can’t go, Winston. You can’t miss your therapy sessions. I want to see you at least once a week.”

“You bitch.”

“I’m trying to do the right thing. What day is good for you?”

“I’ll call you back.”

“Don’t push me, Winston.”

“I have to make this order,” he said. Then, after a second, he said, “Dr. Val?”

“What?”

“Do I have to go off the Serzone?”

“We’ll talk about it in therapy.” She hung up and pulled a Post-it out of Hippocrates’ chest.

“Now if I keep this oath, and break it not, may I enjoy honor, in my life and art, among all men for all time; but if I transgress and forswear myself, may the opposite befall me.”

Does that mean dishonor for all time? she wondered. I’m just trying to do the right thing here. Finally.

She made a note to call Winston back and schedule his appointments.

Four

Estelle Boyet

As September’s promise wound down, a strange unrest came over the people of Pine Cove, due in no small part to the fact that many of them were going into withdrawal from their medications. It didn’t happen all at once—the streets were not full of middle-class junkies rocking and sweating and begging for a fix—but slowly as the autumn days became shorter. And as far as they knew (because Val Riordan had called every one of them), they were experiencing the onset of a mild seasonal syndrome, sort of like spring fever. Call it autumn malaise.

The nature of the medications kept the symptoms spread out over the next few weeks. Prozac and some of the older antidepressants took almost a month to leave the system, so those people slipped into the fray more slowly than those on Zoloft or Paxil or Wellbutrin, which was flushed from the system in only a day or two, leaving the deprived with symptoms resembling a low-grade flu, then a scattered disorientation akin to a temporary case of attention deficit disorder, and, in some, a rebound of depression that dropped on them like a smoky curtain.

One of the first to feel the effects was Estelle Boyet, a local artist, successful and semifamous for her seascapes and idealized paintings of Pine Cove shore life. Her prescription had run out a day before Dr. Val had replaced the supply with sugar pills, so she was already in the midst of withdrawal when she took the first dose of the placebo.

Estelle was sixty, a stout, vital woman who wore brightly colored caftans and let her long gray hair fly around her shoulders as she moved through life with an energy and determination that inspired envy from women half her age. For thirty years she had been a teacher in the decaying and increasingly dangerous Los Angeles Unified School District, teaching eighth graders the difference between acrylics and oils, a brush and a pallet knife, Dali and Degas, and using her job and her marriage as a justification for never producing any art herself.

She had married right out of art school: Joe Boyet, a promising young businessman, the only man she had ever loved and only the third she had ever slept with. When Joe had died eight years ago, she had nearly lost her mind. She tried to throw herself into her teaching, hoping that by inspiring the children she might find some reason to go on herself. In the face of the escalating violence in her school, she resigned herself to wearing a bullet-proof vest under her artist smocks and even brought in some paintball guns to try to gain the pupils’ interest, but the latter only backfired into several incidents of drive-by abstract expressionism, and soon she received death threats for not allowing students to fashion crack pipes in ceramics class. Her students—children living in a hyperadult world where playground disputes were settled with 9 mms—eventually drove her out of teaching. Estelle lost her last reason to go on. The school psychologist referred her to a psychiatrist, who put her on antidepressants and recommended immediate retirement and relocation.

Estelle moved to Pine Cove, where she began to paint and where she fell under the wing of Dr. Valerie Riordan. No wonder then that Estelle’s painting had taken a dark turn over the last few weeks. She painted the ocean. Every day. Waves and spray, rocks and serpentine strands of kelp on the beach, otters and seals and pelicans and gulls. Her canvases sold in the local galleries as fast as she could paint them. But lately the inner light at the heart of her waves, titanium white and aquamarine, had taken on a dark shadow. Every beach scene spoke of desolation and dead fish. She dreamed of leviathan shadows stalking her under the waves and she woke shivering and afraid. It was getting more difficult to get her paints and easel to the shore each day. The open ocean and the blank canvas were just too frightening.

Joe is gone, she thought. I have no career and no friends and I produce nothing but kitschy seascapes as flat and soulless as a velvet Elvis. I’m afraid of everything.

Val Riordan had called her, insisting that she come to a group therapy session for widows, but Estelle had said no. Instead, one evening, after finishing a tormented painting of a beached dolphin, she left her brushes to harden with acrylic and headed downtown—anywhere where she didn’t have to look at this shit she’d been calling art. She ended up at the Head of the Slug Saloon—the first bar she’d set foot in since college.

The Slug was full of Blues and smoke and people chasing shots and running from sadness. If they’d been dogs, they would have all been in the yard eating grass and trying to yak up whatever was making them feel so lousy. Not a bone gnawed, not a ball chased—all tails went unwagged. Oh, life is a fast cat, a short leash, a flea in that place where you just can’t scratch. It was dog sad in there, and Catfish Jefferson was the designated howler. The moon was in his eye and he was singing up the sum of human suffering in A-minor, while he worked that bottleneck slide on the National guitar until it sounded like a slow wind through heartstrings. He was grinning.

Of the hundred or so people in the Slug, half were experiencing some sort of withdrawal from their medications. There was a self-pity contingent at the bar, staring into their drinks and rocking back and forth to the Delta rhythms. At the tables, the more social of the depressed were whining and slurring their problems into each other’s ears and occasionally trading hugs or curses. Over by the pool table stood the agitated and the aggressive, the people looking for someone to blame. These were mostly men, and Theophilus Crowe was keeping an eye on them from his spot at the bar.

Since the death of Bess Leander, there had been a fight in the Slug almost every night. In addition, there were more pukers, more screamers, more criers, and more unwanted advances stifled with slaps. Theo had been very busy. So had Mavis Sand. Mavis was happy about it.

Estelle came through the doors in her paint-spattered overalls and Shetland sweater, her hair pulled back in a long gray braid. Just inside, she paused as the music and the smoke washed over her. Some Mexican laborers were standing there in a group, drinking Budweisers, and one of them whistled at her.

“I’m an old lady,” Estelle said. “Shame on you.” She pushed her way through the crowd to the bar and ordered a white wine. Mavis served it in a plastic beer cup. (She was serving everything in plastic lately. Evidently, the Blues made people want to break glass—on each other.)

“Busy?” Estelle said, although she had nothing to compare it to.

“The Blues sure packs ‘em in,�

�� Mavis said.

“I don’t much care for the Blues,” said Estelle. “I enjoy Classical music.”

“Three bucks,” said Mavis. She took Estelle’s money and moved to the other end of the bar.

Estelle felt as if she’d been slapped in the face.

“Don’t mind Mavis,” a man’s voice said. “She’s always cranky.”

Estelle looked up, caught a shirt button, then looked up farther to find Theo’s smile. She had never met the constable, but she knew who he was.

“I don’t even know why I came in here. I’m not a drinker.”

“Something going around,” Theo said. “I think maybe we’re going to have a stormy winter or something. People are coming out of the woodwork.”

They exchanged introductions and Theo complimented Estelle on her paintings, which he’d seen in the local galleries. Estelle dismissed the compliment.

“This seems like a strange place to find the constable,” Estelle said.

Theo showed her the cell phone on his belt. “Base of operations,” he said. “Most of the trouble has been starting in here anyway. If I’m here already, I can stop it before it escalates.”

“Very conscientious of you.”

“No, I’m just lazy,” Theo said. “And tired. In the last three weeks I’ve been called to five domestic disputes, ten fights, two people who barricaded themselves in the bathroom and threatened suicide, a guy who was going house to house knocking the heads off garden gnomes with a sledgehammer, and a woman who tried to take her husband’s eye out with a spoon.”

“Oh my. Sounds like one day in the life of an L.A. cop.”

“This isn’t L.A.,” Theo said. “I don’t mean to complain, but I’m not really prepared for a crime wave.”

“And there’s nowhere left to run,” Estelle said.

“Pardon?”

“People come here to run away from conflict, don’t you think? Come to a small town to get out of the violence and the competition in the city. If you can’t handle it here, there’s nowhere else to go. You might as well give up.”

“Well, that’s a little cynical. I thought artists were supposed to be idealists.”

“Scratch a cynic and you’ll find a disappointed romantic,” Estelle said.

“That’s you?” Theo asked. “A disappointed romantic?”

“The only man I ever loved died.”

“I’m sorry,” Theo said.

“Me too.” She drained her cup of wine.

“Easy on that, Estelle. It doesn’t help.”

“I’m not a drinker. I just had to get out of the house.”

There was some shouting over by the pool table. “My presence is required,” Theo said. “Excuse me.” He made his way through the crowd to where two men were squaring off to fight.

Estelle signaled Mavis for a refill and turned to watch Theo try to make peace. Catfish Jefferson sang a sad song about a mean old woman doing him wrong. That’s me, Estelle thought. A mean old worthless woman.

Self-medication was working by midnight. Most of the customers at the Slug had given in and started clapping and wailing along with Catfish’s Blues. Quite a few had given up and gone home. By closing time, there were only five people left in the Slug and Mavis was cackling over a drawer full of money. Catfish Jefferson put down his National steel guitar and picked up the two-gallon pickle jar that held his tips. Dollar bills spilled over the top, change skated in the bottom, and here and there in the middle fives and tens struggled for air. There was even a twenty down there, and Catfish dug in after it like a kid going for a Cracker Jack prize. He carried the jar to the bar and plopped down next to Estelle, who was gloriously, eloquently crocked.

“Hey, baby,” Catfish said. “You like the Blues?”

Estelle searched the air for the source of the question, as if it might have come from a moth spiraling around one of the lights behind the bar. Her gaze finally settled on the Bluesman and she said, “You’re very good. I was going to leave, but I liked the music.”

“Well, you done stayed now,” Catfish said. “Look at this.” He shook the money jar. “I got me upward o‘ two hundred dollar here, and that mean old woman owe me least that much too. What you say we take a pint and my guitar and go down to the beach, have us a party?”

“I’d better get home,” Estelle said. “I have to paint in the morning.”

“You a painter? I never knowed me a painter. What you say we go down to the beach and watch us a sunrise?”

“Wrong coast,” Estelle said. “The sun comes up over the mountains.”

Catfish laughed. “See, you done saved me a heap of waiting already. Let’s you and me go down to the beach.”

“No, I can’t.”

“It ‘cause I’m Black, ain’t it?”

“No.”

“‘Cause I’m old, right?”

“No.”

“‘Cause I’m bald. You don’t like old bald men, right?”

“No!” Estelle said.

“‘Cause I’m a musician. You heard we irresponsible?”

“No.”

“‘Cause I’m hung like a bull, right?”

“No!” Estelle said.

Catfish laughed again. “Well, you wouldn’t mind spreadin that one around town just the same, would you?”

“How would I know how you’re hung?”

“Well,” Catfish said, pausing and grinning, “you could go to the beach with me.”

“You are a nasty and persistent old man, aren’t you, Mr. Jefferson?” Estelle asked.

Catfish bowed his shining head, “I truly am, miss. I truly am nasty and persistent. And I am too old to be trouble. I admits it.” He held out a long, thin hand. “Let’s have us a party on the beach.”

Estelle felt like she’d just been bamboozled by the devil. Something smooth and vibrant under that gritty old down-home shuck. Was this the dark shadow her paintings kept finding in the surf?

She took his hand. “Let’s go to the beach.”

“Ha!” Catfish said.

Mavis pulled a Louisville Slugger from behind the bar and held it out to Estelle. “Here, you wanna borrow this?”

They found a niche in the rocks that sheltered them from the wind. Catfish dumped sand from his wing tips and shook his socks out before laying them out to dry.

“That was a sneaky old wave.”

“I told you to take off your shoes,” Estelle said. She was more amused than she felt she had a right to be. A few sips from Catfish’s pint had kept the cheap white wine from going sour in her stomach. She was warm, despite the chill wind. Catfish, on the other hand, looked miserable.

“Never did like the ocean much,” Catfish said. “Too many sneaky things down there. Give a man the creeps, that’s what it does.”

“If you don’t like the ocean, then why did you ask me to come to the beach?”

“The tall man said you like to paint pictures of the beach.”

“Lately, the ocean’s been giving me a bit of the creeps too. My paintings have gone dark.”

Catfish wiped sand from between his toes with a long finger. “You think you can paint the Blues?”

“You ever seen Van Gogh?”

Catfish looked out to sea. A three-quarter moon was pooling like mercury out there. “Van Gogh…Van Gogh…fiddle player outta St. Louis?”

“That’s him,” Estelle said.

Catfish snatched the pint out of her hand and grinned. “Girl, you drink a man’s liquor and lie to him too. I know who Vincent Van Gogh is.”

Estelle couldn’t remember the last time she’d been called a girl, but she was pretty sure she hadn’t liked hearing it as much as she did now. She said, “Who’s lying now? Girl?”

“You know, under that big sweater and them overalls, they might be a girl. Then again, I could be wrong.”

“You’ll never know.”

“I won’t? Now that is some sad stuff there.” He picked up his guitar, which had been leaning on a rock, and b

egan playing softly, using the surf as a backbeat. He sang about wet shoes, running low on liquor, and a wind that chilled right to the bone. Estelle closed her eyes and swayed to the music. She realized that this was the first time she’d felt good in weeks.

He stopped abruptly. “I’ll be damned. Look at that.”

Estelle opened her eyes and looked toward the waterline where Catfish was pointing. Some fish had run up on the beach and were flopping around in the sand.

“You ever see anything like that?”

Estelle shook her head. More fish were coming out of the surf. Beyond the breakers, the water was boiling with fish jumping and thrashing. A wave rose up as if being pushed from underneath. “There’s something moving out there.”

Catfish picked up his shoes. “We gots to go.”

Estelle didn’t even think of protesting. “Yes. Now.”

She thought about the huge shadows that kept appearing under the waves in her paintings. She grabbed Catfish’s shoes, jumped off the rock, and started down the beach to the stairs that led up to a bluff where Catfish’s station wagon waited. “Come on.”

“I’m comin‘.” Catfish spidered down the rock and stepped after her.

At the car, both of them winded and leaning on the fenders, Catfish was digging in his pocket for the keys when they heard the roar. The roar of a thousand phlegmy lions—equal amounts of wetness, fury, and volume. Estelle felt her ribs vibrate with the noise.

“Jesus! What was that?”

“Get in the car, girl.”

Estelle climbed into the station wagon. Catfish was already fumbling the key into the ignition. The car fired up and he threw it into drive, kicking up gravel as he pulled away.

“Wait, your shoes are on the roof.”

“He can have them,” Catfish said. “They better than the ones he ate last time.”

“He? What the hell was that? You know what that was?”

“I’ll tell you soon as I’m done havin this heart attack.”

Five

The Sea Beast

The great Sea Beast paused in his pursuit of the delicious radioactive aroma and sent a subsonic message out to a gray whale passing several miles ahead of him. Roughly translated, it said, “Hey, baby, how’s about you and I eat a few plankton and do the wild thing.”

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

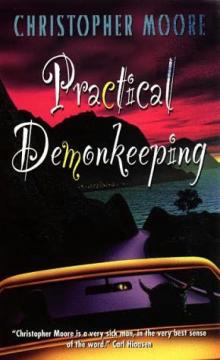

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1