- Home

- Christopher Moore

Fluke Or I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Page 3

Fluke Or I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Read online

Page 3

"So you ichiban big whale kahuna, like Clay say, hey?"

"Yeah," Nate said. "I'm the number-one whale kahuna. You're fired."

"Bummah, mon," The kid said. He shrugged again, turned, and started out the door. "Jah's love to ye, brah. Cool runnings," he sang over his shoulder.

"Wait," Nate said.

The kid spun around, his dreads enveloping his face like a furry octopus attacking a crab. He sputtered a dreadlock out of his mouth and was about to speak.

Quinn held up a finger to signal silence. "Not a word of pidgin, Hawaiian, or Rasta talk, or you're done."

"Okay." The kid waited.

Quinn composed himself and looked around at the mess, then at the kid. "There are papers strewn around all over outside, hanging in the fences, in the bushes. I need you to gather them up and stack them as neatly as you can. Bring them here. Can you do that?"

The kid nodded.

"Excellent. I'm Nathan Quinn." Nate extended his hand to shake.

The kid moved across the room and caught Nate's hand in a powerful grip. The scientist almost winced but instead returned the pressure and tried to smile.

"Pelekekona," said the kid. "Call me Kona."

"Welcome aboard, Kona."

The kid looked around now, looking as if by giving his name he had relinquished some of his power and was suddenly weak, despite the muscles that rippled across his chest and abdomen. "Who did this?"

"No idea." Nate picked up a cassette tape that had been pulled out of the spools and wadded into a bird's nest of brown plastic. "You go get those papers. I'm going to call the police. That a problem?"

Kona shook his head. "Why would it be?"

"No reason. Grab those papers now. Nothing is trash until I look at it, eh?"

"Overstood, brah," Kona said, grinning back at Nate as he headed out into sun. Once outside, he turned and called, "Hey, Kahuna Quinn."

"What?"

"How come them humpies sing like dat?"

"What do you think?" Nate asked, and in the asking there was hope. Despite the fact that the kid was young and irritating and probably stoned, the biologist truly hoped that Kona — unburdened by too much knowledge — would give him the answer. He didn't care where it came from or how it came (and it would still have to be proved); he just wanted to know, which is what set him apart from the hacks, the wannabes, the backstabbers, and the ego jockeys in the field. Nate just wanted to know.

"I think they trying to shout down Babylon, maybe."

"You'll have to explain to me what that means."

"We fix this fuckery, then we fire up a spliff and think over it, brah."

* * *

Five hours later Clay came through the door talking. "We got some amazing stuff today, Nate. Some of the best cow/calf stuff I've ever shot." Clay was still so excited he almost skipped into the room.

"Okay," Nate said with a zombielike lack of enthusiasm. He sat in front of his patched-together computer at one of the desks. The office was mostly put back in order, but the open computer case sitting on the desk with wires spread out to a diaspora of refugee drive units told a tale of data gone wild. "Someone broke in. Tore apart the office."

Clay didn't want to be concerned. He had great videotape to edit. Suddenly, looking at the fans and wires, it occurred to him that someone might have broken his editing setup. He whirled around to see his forty-two-inch flat-panel monitor leaning against the wall, a long diagonal crack bisected the glass. "Oh," he said. "Oh, jeez."

Amy walked in smiling, "Nate you won't believe the — " She pulled up, saw Clay staring at his broken monitor, the computer scattered over Nate's desk, files stacked here and there where they shouldn't be. "Oh," she said.

"Someone broke in," Clay said forlornly.

She put her hand on Clay's shoulder. "Today? In broad daylight?"

Nate swiveled around in his chair. "They went through our living quarters, too. The police have already been here." He saw Clay staring at his monitor. "Oh, and that. Sorry, Clay."

"You guys have insurance, right?" Amy said.

Clay didn't look away from his broken monitor. "Dr. Quinn, did you pay the insurance?" Clay called Nate «doctor» only when he wanted to remind him of just how official and absolutely professional they really ought to be.

"Last week. Went out with the boat insurance."

"Well, then, we're okay," Amy said, jostling Clay, squeezing his shoulder, punching his arm, pinching his butt. "We can order a new monitor tonight, ya big palooka." she chirped, looking like a goth version of the bluebird of happiness.

"Hey!" Clay grinned, "Yeah, we're okay." He turned to Nate, smiling. "Anything else broken? Anything missing?"

Nate pointed to the wastebasket where a virtual haystack of audiotape was spilling over in tangles. "That was spread all over the compound along with all the files. We lost most of the tape, going back two years."

Amy stopped being cheerful and looked appropriately concerned. "What about the digitals?" She elbowed Clay, who was still grinning, and he joined her in gravity. They frowned. (Nate recorded all the audio on analog tape, then transferred it to the computer for analysis. Theoretically, there should be digital copies of everything.)

"These hard drives have been erased. I can't pull up anything from them." Nate took a deep breath, sighed, then spun back around in his chair and let his forehead fall against the desk with a thud that shook the whole bungalow.

Amy and Clay winced. There were a lot of screws on that desk. Clay said, "Well, it couldn't have been that bad, Nate. You got it all cleaned up pretty quickly."

"The guy you hired showed up late and helped me." Nate was speaking into the desk, his face right where it had landed.

"Kona? Where is he?"

"I sent him to the lab. I had some film I want to see right away."

"I knew he wouldn't stand us up on his first day."

"Clay, I need to talk to you. Amy, could you excuse us a minute, please?"

"Sure," Amy said. "I'll go see if anything's missing from my cabin." She left.

Clay said, "You going to look up? Or should I get down on the floor so I can see your face?"

"Could you grab the first-aid kit while we talk?"

"Screws embedded in your forehead?"

"Feels like four, maybe five."

"They're small, though, those little drive-mount screws."

"Clay, you're always trying to cheer me up."

"It's who I am," Clay said.

CHAPTER FOUR

Whale Men of Maui

Who Clay was, was a guy who liked things — liked people, liked animals, liked cars, liked boats — who had an almost supernatural ability to spot the likability in almost anyone or anything. When he walked down the streets of Lahaina, he would nod and say hello to sunburned tourist couples in matching aloha wear (people generally considered to be a waste of humanity by most locals), but by the same token he would trade a backhanded hang-loose shaka (thumb and fingers extended, three middle fingers tucked, always backhand if you're a local) with a crash of native bruddahs in the parking lot of the ABC Store and get no scowls or pidgin curses, as would most haoles. People could sense that Clay liked them, as could animals, which was probably why Clay was still alive. Twenty-five years in the water with hunters and giants, and the worst he'd come out of it was to get a close tail-wash from a southern right whale that tumbled him like a cartoon into the idling prop of a Zodiac. (Oh, there were the two times he was drowned and the hypothermia, but that stuff wasn't caused by the animals; that was the sea, and she'll kill you whether you liked her or not, which Clay did.) Doing what he wanted to do and his boundless affinity for everything made Clay Demodocus a happy guy, but he was also shrewd enough not to be too open about his happiness. Animals might put up with that smiley shit, but people will eventually kill you for it.

"How's the new kid?" Clay said, trying to distract from the iodine he was applying to Nate's forehead while simultaneously calculating the time to ship his new monitor over to Maui from the discount house in Seattle. Clay liked gadgets.

"He's a criminal," Nate said.

"He'll come around. He's a water guy." For Clay this said it all. You were a water guy or you weren't. If you weren't… well, you were pretty much useless, weren't you?

"He was an hour late, and he showed up in the wrong place."

"He's a native. He'll help us deal with the whale cops."

"He's not a native, he's blond, Clay. He's more of a haole than you are, for Christ's sake."

"He'll come around. I was right about Amy, wasn't I?" Clay said. He liked the new kid, Kona, despite the employment interview, which had gone like this:

Clay sat with the forty-two-inch monitor at his back, his world-famous photographs of whales and pinnipeds playing in a slide show behind him. Since he was conducting a job interview, he had put on his very best $5.99 ABC Store flip-flops. Kona stood in the middle of the office wearing sunglasses, his baggies, and, since he was applying for a job, a red-dirt-dyed shirt.

"Your application says that your name is Pelke — ah, Pelekekona Ke — " Clay threw his hands up in surrender.

"I be called Pelekekona Keohokalole — da warrior kine — Lion of Zion, brah."

"Can I call you Pele?"

"Kona," Kona said.

"It says on your driver's license that your name is Preston Applebaum and you're from New Jersey."

"I be one hundred percent Hawaiian. Kona the best boat hand in the Island, yeah. I figga I be number-one good man for to keep track haole science boss's isms and skisms while he out oppressing the native bruddahs and stealing our land and the best wahines. Sovereignty now, but after a bruddah make his rent, don't you know?"

Clay grinned at the blond kid. "You're just a mess, aren't you?"

Kona lost his Rastafarian, laid-backness. "Look, I was born here when my parents were on vacation. I really am Hawaiian, kinda, and I really need this job. I'm going to lose my place to live if I don't make some money this week. I can't live on the beach in Paia again. All my shit got stolen last time."

"It says here that you last worked as a forensic calligrapher. What's that, handwriting analysis?"

"Uh, no, actually, it was a business I started where I would write people's suicide notes for them." Not a hint of pidgin in his speech, not a skankin' smidgen of reggae. "It didn't do that well. No one wants to kill himself in Hawaii. I think if I'd started it back in New Jersey, or maybe Portland, it would have gone over really well. You know business: location, location, location."

"I thought that was real estate." Clay actually felt a twinge of missed opportunity, here, for although he had spent his life having adventures, doing exactly what he wanted to do, and although he often felt like the dumbest guy in the room (because he'd surrounded himself with scientists), now, talking to Kona, he realized that he had never realized his full potential as a self-deluded blockhead. Ahhh… wistful regrets. Clay liked this kid.

"Look, I'm a water guy," Kona said. "I know boats, I know tides, I know waves, I love the ocean."

"You afraid of it?" Clay asked.

"Terrified."

"Good. Meet me at the dock tomorrow morning at eight-thirty."

* * *

Now Nate rubbed at the crisscrrossed band-aids on his forehead as Clay went through the Pelican cases of camera equipment under the table across the room. The break-in and subsequent shit storm of activity had sidetracked him from what he'd seen this morning. It started to settle on him again like a black cloud of self-doubt, and he wondered whether he should even mention what he saw to Clay. In the world of behavioral biology, nothing existed until it was published. It didn't matter how much you knew — it wasn't real if it didn't appear in a scientific journal. But when it came to day-to-day life, publication was secondary. If he told Clay what he'd seen, it would suddenly become real. As with his attraction for Amy and the realization that years' worth of research was gone, he wasn't sure he wanted it to be real.

"So why did you need to send Amy out?" Clay asked.

"Clay, I don't see things I don't see, right? I mean, in all the time we've worked together, I haven't called something before the data backed it up, right?"

Clay looked up from his inventory to see the expression of consternation on his friend's face. "Look, Nate, if the kid bothers you that much, we can find someone else —»

"It's not the kid." Nate seemed to be weighing what he was going to say, not sure if he should say it, then blurted out, "Clay, I think I saw writing on the tail flukes of that singer this morning."

"What, like a pattern of scars that look like letters? I've seen that. I have a dolphin shot that shows tooth rakings on the animal's side that appear to spell out the word 'zap. »

"No it was different. Not scars. It said, 'Bite me. "

"Uh-huh," Clay said, trying not to make it sound as if he thought his friend was nuts. "Well, this break-in, Nate, it's shaken us all up."

"This was before that. Oh, I don't know. Look, I think it's on the film I shot. That's why I came in to take the film to the lab. Then I found this mess, so I sent the kid to the lab with my truck, even though I'm pretty sure he's a criminal. Let's table it until he gets back with the film, okay?" Nate turned and stared at the deskful of wires and parts, as if he'd quickly floated off into his own thoughts.

Clay nodded. He'd spent whole days in the same twenty-three-foot boat with the lanky scientist, and nothing more had passed between the two than the exchange of "Sandwich?" "Thanks."

When Nate was ready to tell him more, he would. In the meantime he would not press. You don't hurry a thinker, and you don't talk to him when he's thinking. It's just inconsiderate.

"What are you thinking?" Clay asked. Okay, he could be inconsiderate sometimes. His giant monitor was broken, and he was traumatized.

"I'm thinking that we're going to have to start over on a lot of these studies. Every piece of magnetic media in this place has been scrambled, but as far as I can tell, nothing is missing. Why would someone do that, Clay?"

"Kids," Clay said, inspecting a Nikon lens for damage. "None of my stuff is missing, and except for the monitor it seems okay."

"Right, your stuff."

"Yeah, my stuff."

"Your stuff is worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, Clay. Why wouldn't kids take your stuff? No one doesn't know that Nikon equipment is expensive, and no one on the island doesn't know that underwater housings are expensive, so who would just destroy the tapes and disks and leave everything?"

Clay put down the lens and stood up. "Wrong question."

"How is that the wrong question?"

"The question is, who could possibly care about our research other than us, the Old Broad, and a dozen or so biologists and whale huggers in the entire world? Face it, Nate, no one gives a damn about singing whales. There's no motive. The question is, who cares?"

Nate slumped in his chair. Clay was right. No one did care. People, the world, cared about the numbers of whales, so the survey guys, the whale counters, they actually collected data that people cared about. Why? Because if you knew how many whales you had, you knew how many you could or could not kill. People loved and understood and thought they could prove points and make money with the numbers. Behavior… well, behavior was squishy stuff used to entertain fourth-graders on Cable in the Classroom.

"We were really close, Clay," Nate said. "There's something in the song that we're missing. But without the tapes…"

Clay shrugged. "You heard one song, you heard 'em all." Which was also true. All the males sang the same song each season. The song might change from season to season, or even evolve through the season somewhat, but in any given population of humpbacks, they were all singing the same tune. No one had figured out exactly why.

"We'll get new samples."

"I'd already cleaned up the spectrographs, filtered them, analyzed them. It was all on the hard disks. That work was for specific samples."

"We'll do it again, Nate. We have time. No one is waiting. No one cares."

"You don't have to keep saying that."

"Well, it's starting to bother me, too, now," Clay said. "Who in the hell cares whether you figure out what's going on with humpback song?"

A kicked-off flip-flop flew into the room followed by the singsong Rastafarian-bruddah pomp of Kona returning, "Irie, Clay, me dready. I be bringing films and herb for the evening to welcome to Jah's mercy, mon. Peace."

Kona stood there, an envelope of negatives and contact sheet in one hand, a film can held high above his head in the other. He was looking up to it as if it held the elixir of life.

"You have any idea what he said?" Nate asked. He quickly crossed the room and snatched the negatives away from Kona.

"I think it's from the 'Jabberwocky, " Clay replied. "You gave him cash to get the film processed? You can't give him cash."

"And this lonely stash can to fill with the sacred herb," Kona said. "I'll find me papers, and we can take the ship home to Zion, mon."

"You can't give him money and an empty film can, Nate. He sees it as a religious duty to fill it up."

Nate had pulled the contact sheet out of the envelope and was examining it with a loupe. He checked it twice, counting each frame, checking the registry numbers along the edge. Frame twenty-six wasn't there. He held the plastic page of negatives up to the light, looked through the images twice and the registry numbers on the edges three times before he threw them down, checked the earlier frames that Amy had shot of the whale tail, then crossed the room and grabbed Kona by the shoulders. "Where's frame twenty-six, goddamn it? What did you do with it?"

"This just like I get it, mon. I didn't do nothing."

"He's a criminal, Clay," Nate said. Then he grabbed the phone and called the lab.

All they could tell him was that the film had been processed normally and picked up from the bin in front. A machine cut the negatives before they went into the sleeves — perhaps it had snipped off the frame. They'd be happy to give Nate a fresh roll of film for his trouble.

* * *

Two hours later Nate sat at the desk, holding a pen and looking at a sheet of paper. Just looking at it. The room was dark except for the desk lamp, which reached out just far enough to leave darkness in all the corners where the unknown could hide. There was a nightstand, the desk, the chair, and a single bed with a trunk set at its end, a blanket on top as a cushion. Nathan Quinn was a tall man, and his feet hung off the end of the bed. He found that if he removed the supporting trunk, he dreamed of foundering in blue-water ocean and woke up gasping. The trunk was full of books, journals, and blankets, none of which had ever been removed since he'd shipped them to the island nine years ago. A centipede the size of a Pontiac had once lived in the bottom-right corner of the trunk but had long since moved on once he realized that no one was ever going to bother him, so he could stand up on his hind hundred feet, hiss like a pissed cat, and deliver a deadly bite to a naked foot. There was a small television, a clock radio, a small kitchenette with two burners and a microwave, two full bookshelves under the window that looked out onto the compound, and a yellowed print of two of Gauguin's Tahitian girls between the windows over the bed. At one time, before the plantations had been automated, ten people probably slept in this room. In grad school at UC Santa Cruz, Nathan Quinn had lived in quarters about this same size. Progress.

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

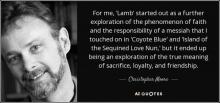

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

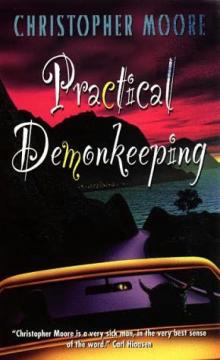

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1