- Home

- Christopher Moore

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Page 20

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Read online

Page 20

He’d found her the morning before, squatting beneath a cow, squirting a stream of milk into her mouth from the udder. There’d been a wooden pail there, ready for the morning milking, but she’d never gotten to it, as the Colorman had lured her away from her task with a bright red apple and a shiny piece of silver dangling from a string.

“Come along, now. Come on.”

He backed his way across the village, leading her to a stable he’d rented, where he’d given her the apple, and beer, and wine spiced with a narcotic mushroom that made her sleep until he’d awakened her today. The promise of another apple lured her to the riverbank.

“Take that off. Off,” said the Colorman, showing her the gesture of lifting her frock over her head.

She made the same gesture but failed to grasp the idea she was supposed to actually remove her dress, a grimy, woven wool arrangement that was tattered at every seam.

The Colorman held the apple up in one hand, then tugged at the cord tied at her waist as a belt.

“Off. Take it off. Apple,” said the Colorman.

The girl giggled at his touch, but what concentration she had was trained on the apple.

The Colorman uncinched her belt with his free hand, then held the apple just out of her reach as he alternately tickled her and worked her dress up to her shoulders and her arms out of the sleeves as she flinched and giggled. Finally he put the apple in her mouth and yanked her dress over her head with both hands as her full being seemed to fold over and around the apple. She stood in the mud, completely naked, except for the small silver coin suspended from a string around her neck.

She was laughing as she gnawed into the apple, and from the noises she was making the Colorman feared that she might choke before he finished his work.

“You like apples, huh?” he said. “I have another one for you after that one.”

He unslung a leather satchel from his back and removed the materials he would need. The blue was in an earthenware jar no bigger than his fist, still in the dry, powdered form, as it had to be for the glassmakers. For this, since it didn’t need to dry, or last very long, he would bind the color in olive oil, which he poured from a bottle into a shallow wooden cup to mix with the Sacré Bleu.

He stirred the mixture with a stick, until it was a smooth, shiny paste, then, with the distraction of another apple and another piece of silver, he applied the blue to the girl’s body as she squirmed and giggled and crunched away on her apple.

“She is going to be angry when she sees you,” said the Colorman, stepping back from the girl and checking over his work. “Very angry, I think.”

There was a large, flat stone tied at the end of the wooden crane, just at the level of the Colorman’s chest, and he pressed down on it the best he could, but the end of the crane in the water remained there. He grunted and hopped and swung back and forth, and still the crane only lifted a few inches.

“Girl, come here,” he said to the simple girl, who was watching him with the fascination of a cat regarding the workings of a clock.

He trudged over to her, took her by the hand, then led her to the large stone.

“Now, help me push.” He mimed pushing down on the stone. The girl watched him, having returned both her hands to guiding the apple into her mouth. Nothing.

He tried to get her to jump up on the stone, but there was no strategic placement of the apple that could get her to do that, and finally, when he couldn’t get her to grasp the concept of boosting him up onto the stone, he lashed her to it with her belt slung under her arms, then scrambled up her body and knelt on the stone as he used the girl for leverage while she made a distressed mooing sound approximating the call of a calf caught in a thicket of thorns.

But the wooden crane moved, and its far end lifted out of the water a charred, twisted mass that looked like a statue of a suffering saint fashioned in pitch. It streamed soot and muddy water back into the river. Here in Chartres, it was the tradition to both burn and drown the witches, so at least he wasn’t sifting bones out of an ash pile, as had been the case in the past.

The Colorman cringed, then chanted something that sounded more like a grunt than a prayer, repeating it until the black mass at the end of the crane cracked, showing pink, burned flesh beneath the surface.

The simple girl stopped mooing, took a great gasping breath, and stepped away from the stone counterbalance, slipping out of her rope belt as she moved. The Colorman was catapulted upward, his twisted form describing a gentle arch in the air before he plopped, ass first, onto the muddy riverbank.

“Oh for fuck’s sake,” said the simple girl, backing away from the whole apparatus.

“I knew you’d be angry,” said the Colorman.

“Of course I’m angry,” said the girl. “I’ve been burnt up.” There was light in the girl’s eyes now, the dullness gone. She wiped the drool from her lips with her arm and spit out the blue pigment.

“I brought you an apple,” said the Colorman, pulling the last apple from his satchel.

The girl looked at him, smeared with the oily blue, then at her own body, covered head to toe in blue, then at him. “Why are you all covered in the blue? You better not have bonked me before you brought me back.”

“Accident,” said the Colorman. “Couldn’t be helped.”

“Oh, what is that?” She crinkled her nose and held her arms out from her sides as if they were foreign, foul things and she could actually escape them if she showed enough disgust. “I smell of shit? Why do I smell of shit?”

“I found you under a cow.”

“Under a cow? What was she doing under a cow?”

“She’s a little slow.”

“You mean I’m an imbecile?”

“Not anymore,” said the Colorman cheerily, holding out the apple, wishing that it would work on Bleu the way it had worked on the slow girl. But no.

“You painted the village idiot blue and bonked her before you pulled me up?”

“Being burned up makes you cranky.”

The filthy, naked blue girl stomped into the muddy river with a growl. When she got to waist level she began to scrub herself and a blue stain floated on the water around her. “Why don’t they ever burn you? You’re involved. You’re part of it. You’re the one making the fucking color.” She punctuated every sentence by splashing a great swan of muddy-blue water at the Colorman.

They had been working around the cathedral glassmakers for two hundred years now, moving from camp to camp with them, from Venice to London, as they built their furnaces and made the glass for the windows at each cathedral site. The Colorman provided the pigment to make a unique hue of blue, the Sacré Bleu, and she seduced the glassmakers. Unfortunately, the furnaces were usually built out in the open, or near a forest where wood could be easily harvested, and the glass, too, was stored either in the open or in makeshift tents, forcing them to make the blue in the open as well, where people could stumble upon them in the process. It was a disturbing process to watch. Medieval people reacted badly to the sight.

“You’re the blue one,” said the Colorman.

“You could have rescued me.”

“I just did.”

“Before the burning.”

“I was busy. Couldn’t be helped. I rescued you that time in Paris. At Notre-Dame.”

“Once! Out of how many times? Peasants have no imagination. No other solutions.” She splashed her point home. “Crops fail? Burn the blue girl. Fever in the village? Burn the blue girl. Badgers ate the miller? Burn the blue girl.”

“When did badgers eat the miller?”

“They didn’t. I’m just using that as an example. But if they did, you know the villagers would burn the bloody blue girl as a remedy. ‘Witch’ this and ‘witch’ that? It’s not like it’s easy seducing a glassmaker into thinking you’re the Virgin bloody Mary and then screwing him into inspiration. I’m telling you, Poopstick, this guilt strategy the Church is working is not good for art.”

“Maybe we s

hould find a new camp of glassmakers,” said the Colorman.

She ducked under the water, scrubbed her hair as long as she could hold her breath, then surfaced with a shudder. “Oh, you think? I don’t guess we can stay here, can we, since everyone knows me as the village idiot? Not much I can do except eat dirt in the square and bonk the sodding priest, is there?”

“You can change.”

“No, I refuse to be burned more than once in the same village; find me a clean frock and we’ll go.”

And so they did.

For eight hundred years, it was thought that the formula for making the blue glass in the windows of the cathedral Notre-Dame de Chartres was lost, when it had simply moved on. For Bleu, the burnings had more or less taken the charm out of Gothic cathedrals.

THE SAYING GOES, “THE MIND OF PARIS IS ON THE LEFT BANK, THE MONEY IS on the Right,” and the mind of the Left Bank was the Latin Quarter, so called because the common language spoken by the university students was Latin and had been for eight hundred years.

“I don’t like the Latin Quarter,” Juliette said. She took a carrot from the Colorman’s bag and crunched off the tip. Étienne made a move to bite the carrot greens and she nudged his nose away with her elbow. “All the students are annoying, with their brooding and their spotty faces. And the good painters are all over on Montmartre or in the Batignolles.”

“Then go find a new painter and live with him,” said the Colorman.

It was her fault he’d had to take an apartment in the Latin Quarter, where he had cached secrets and power she didn’t know about. He wanted to tell her that it was her fault for not getting the Dutchman’s painting, and it was her fault for leaving the baker’s painting behind, and if she hadn’t done that, they might have gotten a nice place in the First Arrondissement, with better shops, Les Halles market, and the Louvre nearby, but she was in that mood she got in sometimes, the mood where heat and memories of playing the Mother of God annoyed her so that she would stab you in the eye with a walking stick, and he didn’t want to press her.

“If we have no blue, what good is a new painter?” Juliette said.

“And the Dutchman’s brother. You don’t think he has our paintings? You know if the Dutchman told the dwarf about us, he told his brother.”

“If he has it, he wouldn’t show it to me. I looked at a hundred of Vincent’s canvases. None painted with Sacré Bleu.”

“You need to fix the brother’s memory.”

“I can’t go back to Montmartre looking like this anymore. When the family starts conking you on the head, it’s time to change strategies. If you want me to go back, I need the blue.”

“If we can get the color, you need to clean this up.” The Colorman took off his hat and scratched his head, a patchy carpet of coarse black hair. He could, perhaps, get the color, but he didn’t want her to know the source, which was going to be awkward, since he’d need her to help him make it. Maybe he should just buy a new gun and start shooting painters. It was much simpler that way. “If you can’t make them forget, the baker and the dwarf, the Dutchman’s brother, then you need to finish them.”

“I know.” She pulled her carrot greens away from Étienne, who snapped at her in protest. Then she noticed that his great erect donkey dick was jutting damply out from under him and off the edge of the sofa. She smacked its tip with her carrot and the donkey brayed like a broken bellows in protest.

“He missed you,” explained the Colorman.

Eighteen

TRAINS IN TIME

IT’S TWO THIRTY. IT’S TWO THIRTY. IT’S TWO THIRTY.”

“You’re supposed to use the watch as a point on which to focus,” said the Professeur, who was swinging his pocket watch by the chain in front of Lucien’s face. “Not to continually check the time.”

“You didn’t say that.” Lucien squinted at the watch. They’d been at this for a half an hour, trying to access Lucien’s earliest memories of the Colorman, but all they’d discovered was the time. “You just said concentrate on the watch. I thought you’d want to know what time it was.”

“When does he start to behave like a chicken?” asked Henri. “I need to get to the printers.”

“A subject for hypnosis must be suggestible,” said the Professeur. “Perhaps we should try it on you, Monsieur Lautrec.”

“And waste the thousands of francs I’ve spent on alcohol trying to destroy the very memories you are trying to raise? I think not. I have an idea, though, that may work on Lucien. Could we try an experiment?”

“Of course,” said the Professeur.

“I’ll need what is left of the blue oil color I gave you for analysis.”

The Professeur retrieved the color from the bedroom/laboratory and gave it to Lautrec, who uncapped the tube.

“I’m not eating paint,” said Lucien.

“You don’t have to eat it,” said Henri. “You merely have to look at it.” And with that, he squeezed a dollop of paint out onto the Professeur’s watch and smeared it around on the face.

“This was my father’s watch,” said the Professeur, frowning at his newly painted timepiece.

“In the name of science!” pronounced Toulouse-Lautrec. “Now try it.” He limped off to the kitchen. “Don’t you at least keep some sherry for cooking?”

The Professeur dangled the watch in front of Lucien’s face. “Now, if you just concentrate on the watch, on the blue.”

Lucien sat bolt upright on the couch. “I don’t see the point of this. What am I going to remember?”

Henri was returning to the parlor with a very dusty bottle of brandy in hand. “We don’t know what you’re going to remember until you remember it.”

“You think it will help me find Juliette?” And therein lay the resistance. Lucien was afraid that the Professeur might, indeed, be able to conjure up lost memories, but what if Lucien remembered that his Juliette was some sort of villain? He couldn’t bear it.

“Wait. Henri, you said that Carmen didn’t remember you, but she wasn’t unkind to you, right? She didn’t seem to be trying to hide from you? Perhaps she was an unwilling participant in the Colorman’s scheme. Perhaps she loved you deeply and he made her forget. Perhaps Juliette, too, is being manipulated against her will.”

“Perhaps,” said Lautrec absentmindedly, “but she is too beautiful, I think, to not be inherently evil.”

Henri was ambling around the room looking in various nooks and crannies, moving different machines and instruments, and finally settled on a small graduated cylinder. He began to pour brandy into it.

“Monsieur,” said the Professeur, shaking his head. “That was last used for a substance that is quite poisonous.”

“Oh balls,” said Lautrec. He snatched the skull of a small animal, a monkey, it appeared, from the Professeur’s desk and poured a dollop of brandy into it, then slurped off the top.

“Henri!” scolded Lucien.

“May I suggest a demitasse from the kitchen,” said the Professeur. “I prepare my own coffee in the morning.”

“Oh, right,” said Henri, draining the monkey skull and replacing it on the desk, then limping back to the kitchen.

“Why don’t you just drink out of the bottle?” Lucien called after him.

Henri’s head popped back around the corner. “Please, monsieur, what am I, a barbarian?”

When they were all settled again in the parlor, Henri with his brandy, the Professeur with his watch, Lucien with his foreboding, the process began again. This time the Professeur spun the watch slowly on its chain while he recited the litany of relaxation, concentration, and sleep to Lucien.

“Your eyelids will feel heavy, Lucien, and you may close them when you wish. When you do, you will fall into a deep sleep. You will still be able to hear me, and answer me, but you will be asleep.”

Lucien closed his eyes and his head slumped forward onto his chest.

“You are completely safe here,” said the Professeur. “Nothing can harm you.”

“If you feel you need to scratch around looking for worms, we will understand,” said Henri.

The Professeur shushed the painter with a finger to his lips, then whispered, “Please, monsieur, I am not going to make him think he is a chicken.” To Lucien he said, “How are you, Lucien?”

“I am completely safe and nothing can harm me.”

“That’s right. Now I’d like you to go back, travel back, back in time. Imagine you are going down a flight of steps, and with each step you take, you go back another year. You will see your past go by, and remember all the pleasant moments, but keep moving until you first encounter this Colorman.”

“I see him,” said Lucien. “I’m with Juliette. We are drinking wine at the Lapin Agile. I can see him out the window. He is standing across the street with his donkey.”

“And how far back have you traveled?”

“Perhaps three years. Yes, three years. Juliette is radiant.”

“Of course she is,” said the Professeur. “But now you need to continue your journey, down the stairs, until you see the Colorman again. Down, down, back through time.”

“I see him!”

“And how far have you gone?”

“I’m young. Maybe fourteen.”

“Are you secretly aroused by the nuns at school?” asked Henri.

“No, there are no nuns,” said Lucien.

“Perhaps it was just me,” Henri said.

“No, it wasn’t just you,” said the Professeur, with no further explanation. “Go on, Lucien, what do you see?”

“It is early morning, and it is raining. I have been out in the rain, but now I’m under a roof. A very high glass roof.”

“And where is this roof?”

“It is a train station. It’s Gare Saint-Lazare. I have been carrying three easels and a paint box for Monsieur Monet. He is still standing out in the rain, talking to the Colorman. The Colorman can’t get his donkey to come under the awning of the station. Monsieur Monet says he has no money for color. He says he is going to capture the fury of smoke and steam. The Colorman hands him a tube of ultramarine. He says this is the only way, and Monet can pay him later. I can’t hear what the Colorman says next, but Monsieur Monet laughs at him and takes the paint.”

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

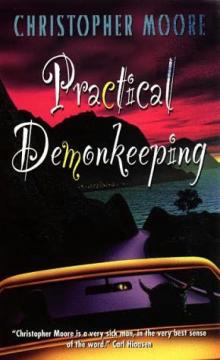

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1