- Home

- Christopher Moore

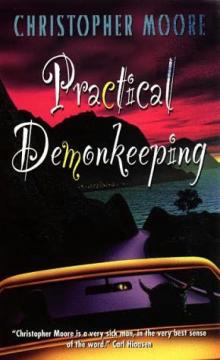

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1 Page 2

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1 Read online

Page 2

Again the village grew, populated by retirees and young couples who eschewed the hustle of the city to raise their children in a quiet coastal town. Harpooner’s Cove became a village of the newly wed and the nearly dead.

In the 1960s the young, environmentally conscious residents decided that the name Harpooner’s Cove hearkened back to a time of shame for the village and that the name Pine Cove was more appropriate to the quaint, bucolic image the town had come to depend on. And so, with the stroke of a pen and the posting of a sign — WELCOME TO PINE COVE, GATEWAY TO BIG SUR — history was whitewashed.

The business district was confined to an eight-block section of Cypress Street, which ran parallel to the coast highway. Most of the buildings on Cypress sported facades of English Tudor half-timbering, which made Pine Cove an anomaly among the coastal communities of California with their predominantly Spanish-Moorish architecture. A few of the original structures still stood, and these, with their raw timbers and feel of the Old West, were a thorn in the side of the Chamber of Commerce, who played on the village’s English look to promote tourism.

In a half-assed attempt at thematic consistency, several pseudo-authentic, Ole English restaurants opened along Cypress Street to lure tourists with the promise of tasteless English cuisine. (There had even been an attempt by one entrepreneur to establish an authentic English pizza place, but the enterprise was abandoned with the realization that boiled pizza lost most of its character.)

Pine Cove’s locals avoided patronage of these restaurants with the duplicity of a Hindu cattle rancher: willing to reap the profits without sampling the product. Locals dined at the few, out-of-the-way cafes that were content with carving a niche out of the hometown market with good food and service rather than gouging an eye out of the swollen skull of the tourist market with overpriced, pretentious charm.

The shops along Cypress Street were functional only in that they moved money from the pockets of the tourists into the local economy. From the standpoint of the villagers, there was nothing of practical use for sale in any of the stores. For the tourist, immersed in the oblivion of vacation spending, Cypress Street provided a bonanza of curious gifts to prove to the folks back home that they had been somewhere. Somewhere where they had obviously forgotten that soon they would return home to a mortgage, dental bills, and an American Express bill that would descend at the end of the month like a financial Angel of Death.

And they bought. They bought effigies of whales and sea otters carved in wood, cast in plastic, brass, or pewter, stamped on key chains, printed on postcards, posters, book covers, and condoms. They bought all sorts of useless junk imprinted with: Pine Cove, Gateway to Big Sur, from bookmarks to bath soap.

Over the years it became a challenge to the Pine Cove shopowners to come up with an item so tacky that it would not sell. Gus Brine, owner of the local general store, suggested once at a Chamber of Commerce meeting that the merchants, without compromising their high standards, might put cow manure into jars, imprint the label with Pine Cove, Gateway to Big Sur, and market it as authentic gray whale feces. As often happens with matters of money, the irony of Brine’s suggestion was lost, a motion was carried, a plan was laid, and if it had not been for a lack of volunteers to do the actual packaging, the shelves of Cypress Street would have displayed numbered, limited-edition jars of Genuine Whale Waste.

The residents of Pine Cove went about their work of fleecing the tourists with a slow, methodical resolve that involved more waiting than activity. Life, in general, was slow in Pine Cove. Even the wind that came in off the Pacific each evening crept slowly through the trees, allowing the villagers ample time to bring in wood and stoke their fires against the damp cold. In the morning, down on Cypress Street, the Open signs flipped with a languid disregard for the times posted on the doors. Some shops opened early, some late, and some not at all, especially if it was a nice day for a walk on the beach. It was as if the villagers, having found their little bit of peace, were waiting for something to happen.

And it did.

-=*=-

Around midnight on the night that The Breeze disappeared, every dog in Pine Cove began barking. During the following fifteen minutes, shoes were thrown, threats were made, and the sheriff was called and called again. Wives were beaten, pistols were loaded, pillows were pounded, and Mrs. Feldstein’s thirty-two cats simultaneously coughed up hairballs on her porch. Blood pressure went up, aspirin was opened, and Milo Tobin, the town’s evil developer, looked out the front window to see his young neighbor, Rosa Cruz, in the nude, chasing twin Pomeranians around her front yard. The strain was too much for his chain-smoker’s heart, and he flopped on the floor like a fish and died.

On another hill, Van Williams, the tree surgeon, had reached the limit of his patience with his neighbors, a family of born-again dog breeders whose six Labrador retrievers barked all night long with or without supernatural provocation. With his professional-model chain saw he dropped a hundred-foot Monterey pine tree on their new Dodge Evangeline van.

A few minutes later, a family of raccoons who normally roamed the streets of Pine Cove breaking into garbage cans, were taken, temporarily, with a strange sapience and ignored their normal activities to steal the stereo out of the ruined van and install it in their den that lay in the trunk of a hollow tree.

An hour after the cacophony began, it stopped. The dogs had delivered their message, and as it goes in cases where dogs warn of coming earthquakes, tornadoes, or volcanic eruptions, the message was completely misconstrued. What was left the next morning was a very sleepy, grumpy village brimming with lawsuits and insurance claims, but without a single clue that something was coming.

-=*=-

At six that morning a cadre of old men gathered outside the general store to discuss the events of the night before, never once letting their ignorance of what had happened interfere with a good bull session.

A new, four-wheel-drive pickup pulled into the small parking lot, and Augustus Brine crawled out, jangling his huge key ring as if it were a talisman of power sent down by the janitor god. He was a big man, sixty years old, white haired and bearded, with shoulders like a mountain gorilla. People alternately compared him to Santa Claus and the Norse god Odin.

“Morning, boys,” Brine grumbled to the old men, who gathered behind him as he unlocked the door and let them into the dark interior of Brine’s Bait, Tackle, and Fine Wines. As he switched on the lights and started brewing the first two pots of his special, secret, dark-roast coffee, Brine was assaulted by a salvo of questions.

“Gus, did you hear the dogs last night?”

“We heard a tree went down on your hill. You hear anything about it?”

“Can you brew some decaf? Doctor says I’ve got to cut the caffeine.”

“Bill thinks it was a bitch in heat started the barking, but it was all over town.”

“Did you get any sleep? I couldn’t get back to sleep.”

Brine raised a big paw to signal that he was going to speak, and the old men fell silent. It was like that every morning: Brine arrived in the middle of a discussion and was immediately elected to the role of expert and mediator.

“Gentlemen, the coffee’s on. In regard to the events of last night, I must claim ignorance.”

“You mean it didn’t wake you up?” Jim Whatley asked from under the brim of a Brooklyn Dodgers baseball cap.

“I retired early last night with two lovely teenage bottles of cabernet, Jim. Anything that happened after that did so without my knowledge or consent.”

Jim was miffed with Brine’s detachment. “Well, every goddamn dog in town started barking last night like the end of the world was coming.”

“Dogs bark,” Brine stated. He left off the “big deal” — it was understood from his tone.

“Not every dog in town. Not all at once. George thinks it’s supernatural or something.”

Brine raised a white eyebrow toward George Peters, who stood by the coffee machine sporting a dazz

ling denture grin. “And what, George, leads you to the conclusion that the cause of this disturbance was supernatural?”

“Woke up with a hard-on for the first time in twenty years. It got me right up. I thought I’d rolled over on the flashlight I keep by the bed for midnight emergencies.”

“How were the batteries, Georgie?” someone interjected.

“I tried to wake up the wife. Whacked her on the leg with it just to get her attention. I told her the bear was charging and I have one bullet left.”

“And?” Brine filled the pause.

“She told me to put some ice on it to make the swelling go down.”

“Well,” Brine said, stroking his beard, “that certainly sounds like a supernatural experience to me.” He turned to the rest of the group and announced his judgment. “Gents, I agree with George. As with Lazarus rising from the dead, this unexplained erection is hard evidence of the supernatural at work. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have cash customers to attend to.”

The last remark was not meant as a dig toward the old men, whom Brine allowed to drink coffee all day free of charge. Augustus Brine had long ago won their loyalty, and it would have been absurd for any one of them to think of going anywhere else to purchase wine, or cheese, or bait, or gasoline, even though Brine’s prices were a good thirty percent higher than the Thrifty-Mart down the street.

Could the pimple-faced clerks at the Thrifty-Mart give advice on which bait was best for rock cod, a recipe for an elegant dill sauce for that same fish, recommend a fine wine to complement the meal, and at the same time ask after the well-being of every family member for three generations by name? They could not! And therein lay the secret of Augustus Brine’s ability to run a successful business based entirely on the patronage of locals in an economy catering to tourists.

Brine made his way to the counter, where an attractive woman in a waitress apron awaited, impatiently worrying a five-dollar bill.

“Five dollars worth of unleaded, Gus.” She thrust the bill at Brine.

“Rough night, Jenny?”

“Does it show?” Jenny made a show of fixing her shoulder-length auburn hair and smoothing her apron.

“A safe assumption, only,” Brine said with a smile that revealed teeth permanently stained by years of coffee and pipe smoke. “The boys tell me there was a citywide disturbance last night.”

“Oh, the dogs. I thought it was just my neighborhood. I didn’t get to sleep until four in the morning, then the phone rang and woke me up.”

“I heard about you and Robert splitting up,” Brine said.

“Did someone send out a newsletter or something? We’ve only been separated a few days.” Irritation put an unattractive rasp in her voice.

“It’s a small town,” Brine said softly. “I wasn’t trying to be nosy.”

“I’m sorry, Gus. It’s just the lack of sleep. I’m so tired I was hallucinating on the way down here. I thought I heard Wayne Newton singing ‘What a Friend We Have in Jesus.’”

“Maybe you did.”

“The music was coming from a pine tree. I’m telling you, I’ve been a basket case all week.”

Brine reached across the counter and patted her hand. “The only constant in this life is change, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Give yourself a break.”

Just then Vance McNally, the local ambulance driver, burst through the door. The radio on his belt made a sizzling sound as if he’d just stepped out of a deep fryer. “Guess who vapor locked last night?” he said, obviously hoping that no one would know.

Everyone turned and waited for his announcement. Vance basked in their attention for a moment to confirm his self-importance. “Milo Tobin,” he said, finally.

“The evil developer?” George asked.

“That’s him. Sometime around midnight. We just bagged him,” Vance said to the group. Then to Brine, “Can I get a pack of Marlboros?”

The old men searched each other’s faces for the right reaction to Vance’s news. Each was waiting for another to say what they were all thinking, which was, “It couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy,” or even, “Good riddance,” but as they were all aware that Vance’s next rude announcement could be about them, they tried to think of something nice to say. You don’t park in the handicapped space lest the forces of irony give you a reason to, and you don’t speak ill of the dead unless you want to get bagged next.

Jenny saved them. “He sure kept that Chrysler of his clean, didn’t he?”

“Sure did.”

“The thing sparkled.”

“He kept it like new, he did.”

Vance smiled at the discomfort he had caused. “See you boys later.” He turned to leave and bumped straight into the little man standing behind him.

“Excuse me, fella,” Vance said.

No one had seen him come in or had heard the bell over the door. He was an Arab, dark, with a long, hooked nose and old; his skin hung around his piercing gray-blue eyes in folds. He wore a wrinkled, gray flannel suit that was at least two sizes too big. A red stocking cap rode high on the back of his bald head. His rumpled appearance combined with this diminutive size made him look like a ventriloquist’s dummy that had spent a long time in a small suitcase.

The little man brandished a craggy hand under Vance’s nose and let loose with a string of angry Arabic that swirled through the air like blue on a Damascus blade. Vance backed out the door, jumped into his ambulance, and motored away.

Everyone stood stunned by the ferocity of the little man’s anger. Had they really seen blue swirls? Were the Arab’s teeth really filed to points? Were, for that moment, his eyes glowing white-hot? It would never be discussed.

Augustus Brine was the first to recover. “Can I help you with something, sir?”

The unnatural light in the Arab’s eyes dimmed, and in a humble, obsequious manner he said, “Excuse me, please, but could I trouble you for a small quantity of salt?”

3

TRAVIS

Travis O’Hearn was driving a fifteen-year-old Chevy Impala he had bought in L.A. with money the demon had taken from a pimp. The demon was standing on the passenger seat with his head out the window, panting into the rushing coastal wind with the slobbering exuberance of an Irish setter. From time to time he pulled his head inside the car, looked at Travis, and sang, “Your mother sucks cocks in he-ell, Your mother sucks cocks in he-ell,” in a teasing, childlike way. Then he would spin his head around several times for effect.

They had spent the night in a cheap motel north of San Junipero, and the demon had tuned the television to a cable channel that played an uncut version of The Exorcist. It was the demon’s favorite movie. At least, Travis thought, it was better than the last time, when the demon had seen The Wizard of Oz and had spent an entire day pretending to be a flying monkey, or screaming, “And that goes for your little dog, too.”

“Sit still, Catch,” Travis said. “I’m trying to drive.”

The demon had been wired since he had eaten the hitchhiker the night before. The guy must have been on cocaine or speed. Why did drugs affect the demon when poisons did not phase him? It was a mystery.

The demon tapped Travis on the shoulder with a long reptilian claw. “I want to ride on the hood,” he said. His voice was like rusty nails rattling in a can.

“Enjoy,” Travis said, waving across the dashboard.

The demon climbed out the window and across the front, where he perched like a hood ornament from hell, his forked tongue flying in the wind like a storm-swept pennon, spattering the windshield with saliva. Travis turned on the wipers and was grateful to find that the Chevy was equipped with an interval delay feature.

It had taken him a full day in Los Angeles to find a pimp who looked as if he were carrying enough cash to get them a car, and another day for the demon to catch the guy in a place isolated enough to eat him. Travis insisted that the demon eat in private. When he was eating he became visible to other people. He also tripled in size.

<

br /> Travis had a recurring nightmare about being asked to explain the eating habits of his traveling companion.

In the dream Travis is walking down the street when a policeman taps him on the shoulder.

“Excuse me, sir,” the policeman says.

Travis does a slow-mo Sam Peckenpah turn. “Yes,” he says.

The policeman says, “I don’t mean to bother you — but that large, scaly fellow over there munching on the mayor — do you know him?” The policeman points toward the demon, who is biting off the head of a man in a pinstriped polyester suit.

“Why, yes, I do,” Travis says. “That’s Catch, he’s a demon. He has to eat someone every couple of days or he gets cranky. I’ve known him for seventy years. I’ll vouch for his lack of character.”

The policeman, who has heard it all before, says, “There’s a city ordinance against eating an elected official without a permit. May I see your permit, please?”

“I’m sorry,” Travis says, “I don’t have a permit, but I’ll be glad to get one if you’ll tell me where to go.”

The cop sighs and begins writing on a ticket pad. “You can only get a permit from the mayor, and your friend seems to be finishing him off now. We don’t like strangers eating our mayor around here. I’m afraid I’ll have to cite you.”

Travis protests, “But if I get another ticket, they’ll cancel my insurance.” He always wondered about this part of the dream; he’d never carried insurance. The cop ignores him and continues to write out the ticket. Even in a dream, he is only doing his job.

Travis thought it terribly unfair that Catch even invaded his dreams. Sleep, at least, should provide some escape from the demon, who had been with him for seventy years, and would be with him forever unless he could find a way to send him back to hell.

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1