- Home

- Christopher Moore

Noir Page 17

Noir Read online

Page 17

Butch moved through the club like a shark patrolling a reef, which is to say, with the smooth grace of knowing no one dares fuck with you. Sammy thought that Jimmy must be good at spotting talent and he doubled down on the thought when Mel, the bartender, came over. She was a stunner—tall, angular, and androgynous. Short blonde hair brushed up into a pompadour. She’d be a knockout in an evening dress at a cocktail party and look just as good in a tux escorting a Nob Hill broad to the opera. Tonight she was in the same togs Sammy wore to work, black-and-whites, vest, garters on the sleeves, except she wore a pearl choker with an onyx teardrop under her open collar instead of a tie.

“Butch says to set you up,” she said. “On the house. What can I get you?”

“Gimlet,” Sammy said, then cringed a little, like he was ordering up a memory—that first night at Stilton’s when they drank gimlets mixed right in the bottle . . . “Beefeater’s if you got it, but well gin’s fine, too.”

“Got it,” said Mel. As she made his drink, Sammy looked around. The place was dark now, smoky, but it was a big room with a runway stage—lots of tinsel and shine on it. When the show was on, probably all you could see were the entertainers and the stage lights, but now he could see through the crepuscular haze where this was still a seaside warehouse—ductwork and wiring painted black to disappear, heavy pulleys and hooks hiding in the rafters. The carpet was dark red, matted with years of traffic and a thousand sloshed drinks. At the tables were mostly couples, talking soft, heads close together, dressed in suits and dresses, some wound up in each other’s arms, others smoking and listening and staring into each other’s eyes over dying candles and half-finished cocktails. All women.

One dame at a table by the stage, dressed like a guy, looked up from her girly partner to Sammy and gave him an are you lookin’ for trouble? glare. Sammy looked away. Not only was he not looking for trouble, but he did not know how to proceed with a dame if he found it, as his pop taught him that you must never hit a girl, especially your sister, even if she was being a pest.

Butch returned from the back at the same time Sammy’s drink arrived.

“Come with me,” Butch said. “You can bring your drink.”

Sammy flipped a tip on the bar with a toast to Mel over his shoulder as he followed Butch through the club to a discreet door behind a screen, down a short hallway made of rough lumber painted blood-red, to a black lacquered door marked private. Butch held the door for Sammy. He entered, found himself standing before an aircraft carrier desk made of some dark wood, walnut maybe—streamlined and trimmed out with bits of brass set into the wood—the finish around the rounded corners showing wear from countless thighs brushing past. Sammy figured the desk was about as old as he was, the dame behind it, somewhat older.

Jimmy Vasco stood up as Sammy entered. She was exactly as described by Milo and the Russian granny, except she was not wearing lipstick or a tailcoat—but the tux shirt was there, with French cuffs held closed with diamond-studded initials: J.V. She was shorter and older than Sammy expected—five two, maybe forty years old—but she could pass for a younger guy.

“Jimmy, Jimmy Vasco,” she said, offering her hand.

“Sammy Tiffin,” Sammy said, shaking, looking her in the eye the way his dad taught him, man-to-man. She smiled, a crooked smile, like she had something up her sleeve.

She gestured for him to sit. He sat. She sat. She said, “So how do you know Myrtle?” Down to business right away.

“I don’t, really, Mr.—” He caught himself.

Jimmy threw her head back and laughed, a full guffaw, then snorted and dismissed his discomfort with a wave. “It’s okay. Just Jimmy. Go on.”

Sammy liked her on the spot. Since he had come to the city he had become used to being the odd one out, but never was he put at ease so quickly. The thing Milo didn’t tell him? Jimmy Vasco was a stand-up guy—kind of. He could see her sharing lies over spiked coffee and meat loaf with the guys at Cookie’s.

“I barely know Myrtle,” Sammy said. “Met her once. She works at the five-and-dime with a gal I’ve kind of been seeing, and they’re both missing. As far as anyone can tell, anyway. I figure maybe they’re together. I’m worried sick.”

“And what brings you here?”

“Myrtle’s neighbor lady sees someone looks a lot like you through the peephole, picking up clothes and whatnot. I asked around.”

Jimmy nodded, fit a Pall Mall into a holder, and offered one to Sammy. He shook it off. She lit hers.

She said, “You know, Sammy, most of the time a guy shows up here looking for his girl, he’s in store for a big surprise. Sometimes the girls go away with the guy, claim it was all a big mistake, they was just here for the show. Sometimes they stay, and sometimes it gets unpleasant and the gentleman is persuaded to leave.”

“That’s not me,” Sammy said.

“So you got it bad for Stilton, do you?”

“You could say,” he said.

Jimmy nodded, smoked thoughtfully—blew a stream of smoke to the corner.

“Myrt, you wanna come in here, help this poor mope out?”

A louvered door over by some file cabinets opened and out stepped the gangly redhead that was Myrtle, gray slacks and a white silk blouse—heels. She kept her eyes to the floor and moved in tiny sidesteps over behind the desk, next to Jimmy. Jimmy put a protective hand on her waist.

“Hi, Sammy,” Myrtle said, still not looking up.

Sammy looked from the door, which he hadn’t noticed before, to Myrtle, to the door.

“Hi, Myrtle.” Then, to Jimmy, “Is that a closet?”

Jimmy burst out laughing, blasting a cloud of smoke and spittle over the desk—the laugh broke down into a cough. She gasped. After a second she regained her composure, butted her cigarette in a marble ashtray, wiped a tear from her eye, and pulled Myrtle close, hugged her hip.

“Why yes, Sammy, in a manner of speaking, I guess it is, but it is also my dressing room, and there’s a bed and a shower back there. You know, club hours—you bunk where you can. But for Myrt, right now, that would be what we call the closet.” She gave Myrtle an affectionate squeeze at the waist. Myrtle looked down at the desk, mortified.

“You gotta promise not to tell Tilly,” Myrtle said to Sammy. “She’d just shit.”

“She’s not here, then?” Sammy said. When he saw Myrtle he’d really hoped he’d found them both.

“No,” said Myrtle. “I’m not sure where she is.”

“But you’ve seen her?” The tone of her voice gave him a chill.

“Tell him,” Jimmy said.

Myrtle came around the desk like she was pleading a case to Sammy. “Tilly ain’t no floozie, you shouldn’t oughta think that. We was just trying to pick up a little folding money. And that douche bag guy, Sal, offered us a hundred bucks for one night. Actually fifty bucks, but Tilly talked him up.”

“Sal Gabelli?”

“Yeah, guy that owns that bar you work in. He comes on to me and Tilly last week at Vanessi’s, says if we go on this campout up in Sonoma, he’ll give us a hundred bucks apiece. All we have to do is be nice to some rich guys, maybe a little dancing. Nothing else. So we think, why not?”

“This is the Bohemian Club thing?” Sammy asked. It was all falling into place. Fucking Sal. He had thought the campout was another of Sal’s goofball plans, like the dog pizza.

“Yeah, that’s them. So Sal calls me, tells me he’ll pick us up at my place. We’re expecting a car, but what shows up is a bus, like a little bus, and there’s a bunch of other girls on it—I don’t know, eighteen–twenty, all of them are scrubbed up like farm girls. No makeup or lipstick. Me and Tilly were just in our on-the-town duds and I’ll tell you, when we saw this bunch, we both felt like tramps. A lot of them were dressed like Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz, I don’t know why. But then, on the drive up, which takes an hour and a half, we find out that they aren’t farm girls at all—they are all working girls, from Mabel’s.”

Sammy rai

sed a hand to stop her. “Myrtle, where is Stilton?”

“I’m getting to that. Give me a second. So we get to this camp, and I gotta tell you, these guys have got to have some serious cheddar, because they have some of the biggest trees I ever seen.”

“Doll face,” Jimmy interjected. “Strictly speaking, I don’t think the size of their trees has anything to do with their income.” Jimmy gave Sammy a roll of the eyes: Dames, whadda ya gonna do?

“Stilton?” Sammy said, bringing Myrtle back to the point.

“So the bus driver gets stopped at the gate, and the guys at the gate get very stern about no dames in the camp. But the driver says, ‘Alton Stoddard the Third,’ and I remember the name because it is like magic words, and the guys at the gate waved us through. Then the driver just dumps us off in this dirt parking lot in the woods. Don’t get me wrong, they’re nice woods, but all of a sudden we’re just a bunch of girls standing around waiting to get raped and murdered and whatnot.”

Sammy cringed and Myrtle dismissed his concern with a wave.

“But it’s fine. Pretty soon some guys in ranger shirts or something come down and they go on about it being strictly ‘no dames.’ Then one of the working girls, a tall, skinny gal like me, only blonde, called Pearl, says ‘Alton Stoddard the Third.’ Again with the magic words. Suddenly the ranger guys lead us up this little road to a dining hall with a kitchen and there’s chili cooking and other snacks and guys bartending in white coats and so forth. The bartenders and the guys serving are from the city. The guys in the ranger shirts are country guys that live in those little towns up there in the redwoods. But these local guys skedaddle and the bartenders are very nervous about breaking the no-dames policy, even when Pearl says ‘Alton Stoddard the Third,’ they hustle us into a room behind the kitchen which is their dining room. Suddenly Tilly and I are happy we took our hundred bucks up front, which sets off the working girls when we mention it because they are not paid up front or anywhere near a hundred bucks.

“So we are peeking through the crack in the door when the Bohemians start coming in, and most of them are older guys, like banker types, but you can’t tell, because they are wearing work pants and stuff, although none of them looks like he has done a day of work in his life.

“Pretty soon they have all split up and taken off into campsites, and the bartenders tell us we should just relax until they consult with whoever brings us here. Well, none of them have ever heard of Sal, but they have heard of Alton Stoddard the Third, and Tilly says that it’s a good thing because she thinks if they don’t we might all be buried in a trench somewhere. She’s a hoot. What a joker that girl is.” Here Myrtle leaned over the desk, so her face was even with Sammy’s, and she said, “At least that is what I think at the time!”

“Oh hell,” said Sammy, hopeless.

“Baby, don’t do that,” said Jimmy.

“What?”

“The drama, doll. Don’t add the drama.”

“It’s how I tell a story.”

“But Sammy here does not need the extra drama. Look at the poor guy, he’s dramatized already. Also, he has probably already figured out that you do not end up buried in a trench in this story.”

“Sorry, Sammy,” Myrtle said, demurely. She came around the desk, sat in the chair next to him, patted his arm. “There, there, sweetheart, Tilly is probably not dead in a trench.”

“But you never know,” said Jimmy, like a little ray of sunshine.

15

Let’s Say, Tax Guys

Because he was a higher rank, Bailey got to take the feet and Hatch had to take the shoulders. When you’re loading a cold, wet, dead Italian onto an airplane, the guy with the shoulders is going to get a lot wetter. Rank has its privileges. The only thing Bailey knew about Hatch, other than that they were roughly the same size physically, was that Hatch held a lower rank. He didn’t know his real name, where he was from, or even if he was married, and he wasn’t supposed to know. They belonged to an agency that was so new, and so secret, that it had failed its basic mission the day the second guy joined, so, except for the immediate instructions for the mission, which they received from a monotone voice at the other end of a long-distance phone number, they knew nothing about each other. Until tonight, when they were instructed to meet two other agents and drop off the Italian, Bailey and Hatch thought they were the only members of the agency.

Bailey was nervous about it. He didn’t trust these other agents. He wasn’t supposed to.

The Chrysler was parked at the end of a deserted runway that was the Santa Rosa airport, about twenty yards from a DC-10 with air force markings, which was where they were taking the dead Italian. Sal Gabelli was frozen in a sitting position and had little chunks of ice clinging to his clothing. He streamed meltage on the runway as they carried him.

“I can’t wait until this is over and we can go back to hunting Nazis,” Hatch said.

“Commies,” said Bailey.

“Yeah. That’s what I meant. Commies. Sorry. Old habits.”

“Down,” Bailey said, when they were under the left wing. They lowered the corpsicle to the ground.

Hatch rubbed his hands together for warmth and tried to look through the passenger windows of the airplane. “I can’t see anything. Are they in there?”

Bailey looked over the top of his sunglasses. They had been issued the glasses and told to wear them at all times. Evidently, the subject might be capable of producing some kind of radiation that would burn the retina and the glasses would protect them. Bailey sometimes took them off to sleep, which made him feel quite the rebel. Over the sunglasses he could see the beam of a flashlight playing around the inside of the airplane. They were in there.

They had to have heard the Chrysler pull up, the trunk open, Hatch yammering on like an auctioneer on truth serum about Nazis and sunglasses. Why didn’t they come out? He fished a quarter out of his pocket and tapped it on the wing. The latch on the small door behind the wing turned and the door swung open. A man in a black fedora knelt in the doorway and lowered a small set of stairs, then came down them and joined them beside the melting Italian.

“Clarence,” said the new agent. He didn’t offer his hand. He wore a black suit, a white shirt, a thin black tie, and sunglasses.

“Bailey,” Bailey said. “Hatch,” he said, pointing to Hatch.

Hatch touched the brim of his hat. Vestigial salute instinct. Bailey frowned at him.

“Everything in order?” Bailey asked Clarence.

“Two on board.”

“Dead?”

“Soon. Ether and Pentothal. Enough fuel to get it to altitude. Just need to get this one aboard.”

“Just two?”

“The others are yours,” said Clarence.

“Nothing else. They give you anything?”

“Nothing. The general denied it all. He was indignant. The woman knew nothing.”

Bailey was at an impasse. Clarence hadn’t mentioned the subject. Did he not know that was what he was looking for—why they were there? He could ask him what he knew, but then that would be tipping his hand that he knew more. Of course, he could lie, but was he supposed to? He didn’t even know if Clarence outranked him.

“You have any leads on the others?” Clarence asked.

“They may be holed up with a club owner named Jimmy Vasco,” Bailey said. “We were on our way there when we called for orders at zero-zero hours.”

“What about the subject?” Hatch asked. Bailey wanted to draw his .45 and shoot his partner on the spot. Blabbermouth!

“No word,” said Clarence. “The general claims he was knocked out. When he came to, the subject was gone.”

“Taken?” said Bailey.

“Well, presumably,” said Clarence, with much more sarcasm than Bailey cared for.

“After?”

“Pick up my partner, then back to the Grove,” said Clarence. “Mop up and stand down until orders at zero eight hundred.”

There were footst

eps from the plane and Bailey turned to see another agent coming down the stairs. “Potter,” said the new man. “Let’s get this one on board so I can get in the air.” Potter wore sunglasses, a black fedora, and a parachute pack. Over a blue suit.

A blue suit.

Bailey felt the order in his world spin into chaos.

* * *

It was getting late, and Sammy needed to call Bennie at the saloon before the place shut down, but first he had to keep from strangling Myrtle for not getting to the point on the whereabouts of the Cheese.

Myrtle said, “Anyway, all us girls are in the room behind the kitchen enjoying cocktails and filing our nails and talking about the pictures and stuff, and after it gets dark, we start to hear music coming from farther back in the woods. And Tilly says she’s going to go see what’s shakin’, even though the bartender told us to stay put. Well, the rest of the girls could care less, they just want to do what they were brought up for and go back to the city and get paid, but Tilly is not having it. We have had a few cocktails, and I don’t know if you’ve been around her when she gets a little hooted, but she can be a firecracker. You tell her the sky is blue and she will fight you about it. So Tilly and I excuse ourselves to go to the little girls’ room, which there aren’t any, and Pearl wants to tag along, so she does. Anyway, Tilly finds a back door through the kitchen and out we go. Up into the woods.

“There is a path, with gravel and everything, but I am a city girl, and it is the woods, at night, so naturally I am thinking, Lions and tigers and bears, oh my! Right? I want to head back out to the gate, but there is a Benny Goodman song playing in the distance, and Tilly says lions and tigers and bears do not go for swing music in the least, so I go along with her and Pearl, who is turning out to be a pretty savvy broad, because as we come up on this big clearing with a lot of torches and chairs arranged like a theater, she pulls a camera out of her pocketbook. One of those little German jobs, like you see in the pictures.

“So we creep up on this clearing that is a little lake with about a thousand guys sitting around it in folding chairs, and in the middle of this lake is a big giant owl. Like five stories tall, which is large, in my book, for an owl. But this one is made of stone or cement or something, and they’ve got it lit up all spooky with torches and whatnot. And the band starts playing this spooky music, just drums and tubas and so forth, and these guys come out from behind the owl in red robes, with hoods covering their faces.

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

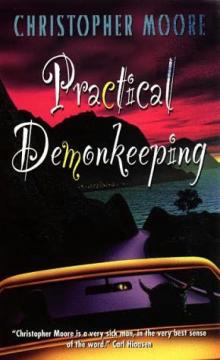

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1