- Home

- Christopher Moore

Noir Page 11

Noir Read online

Page 11

“Thanks, folks,” the counter guy said, but they were already out the door—Sammy, with a hand on her hip, was steering Stilton toward a ride called the Ship of Joy.

“You’re not even limping,” Stilton said. “Guess you were right about the cane.”

“I’m right about most stuff,” Sammy said. “It’s a curse.” He gave her hip a little squeeze to mark the nonsense he was talking.

The Ship of Joy was two ship-shaped gondolas, each seating twelve people, that swung on long pendulums and approximated the experience of being on a big playground swing with a bunch of strangers. They swung and they laughed, mostly at some kids who whooped like they were going over a cliff with every swing, but also at a dad who had lost his hat on the first swing, then stared forlornly for the rest of the ride at the spot over the shooting gallery where it had drifted.

As they were stumbling off the Ship of Joy, arm in arm, Stilton said, “I was expecting more joy.”

“Kind of a phonus bolognus in the ship department as well,” Sammy said.

“Ooh, I love it when you speak Latin. You been to sea?”

Sammy hoped she didn’t see panic on his face. “Just transport,” he lied.

“My husband was on a ship. Heavy cruiser. Went down with all hands near Savo Island, August ’42. They never found him. Uncle Sam sent me a flag.”

Casual as you please, like that first day in the saloon when she’d mentioned her husband. And, like then, he didn’t know what to say. He said, “Sorry, kid.” He pulled her close.

She pushed him away, took his hand, and pulled him toward the games of chance. “Come on, win me something.”

Sammy threw some baseballs at milk bottles filled with concrete and threatened them not at all, although Stilton cheered him on and cursed the bottles’ stubborn ways. At a shooting gallery he downed a few metal ducks with a .22, because his father had given him and his brothers BB guns as boys and he was not a bad shot, although not good enough to win a prize.

“C’mon, let’s kill some clowns,” she suggested, pointing toward a booth where you could throw darts to pop the balloon bodies of painted-on clowns.

“How ’bout you, little lady?” called a barker as they passed. “Guess your weight for a nickel! I get it wrong and you win a teddy bear.”

“And you get it right and I’ll rip your lips off and stomp them like slugs,” replied the Cheese. Sammy nodded earnestly to the barker to confirm her conviction. Stilton’s weight went unguessed.

Sammy finally won her a prize when a ping-pong ball he tossed settled into one of a hundred baseball-size goldfish bowls, startling the fish inside somewhat, but which it soon forgot.

Stilton held the bowl aloft and looked at the perky orange occupant against the lights of the Ferris wheel. “He looks so lonely, Sammy. Win me another one so they can both be in the same bowl and have a little goldfish razzmatazz.”

“I don’t think goldfish have razzmatazz,” said Sammy.

“Well, then how do they have little goldfish?”

“Far as I know, the female lays her eggs on the bottom, then later on the male comes along and fertilizes them.”

“Really?”

“Not exactly sure with goldfish, but that’s how it works for trout. We had trout in Idaho. I read a book on them when I was a kid.”

“Yeah,” said the scruffy guy working the goldfish booth. (You could have sanded the varnish off a coffee table on his five o’clock shadow.) “He’s got it right.”

Stilton handed the fish back to Five O’Clock Shadow. “Take this sad fish. Give him to a kid. Come, Sammy, I need fun.” She took his arm and led him toward the funhouse with the great yellow letters painted across the red façade reading laff in the dark. Sammy bought two tickets and they entered through a giant clown’s mouth, stepping through baffles of black fabric until they were stumbling inside a ten-foot-high, rotating drum. It wasn’t dark yet, but they were laughing and stumbling until they stepped out onto a very mushy field of what must have been black foam rubber.

“It’s like walking on meat loaf,” said the Cheese, giggling, as a skeleton dropped from above them and was caught by a red spotlight. Stilton yipped and jumped into Sammy’s arms. He carried her through another set of black fabric draperies and into complete darkness.

“Should be called Pee in the Dark,” said Stilton.

“Really?”

“Nah. Close, though.”

“C’mere, ’fraidy cat,” said Sammy. He smooched her perhaps a little too zealously for someone who was laughing and they banged their teeth. Then they separated and felt for chipped teeth with their tongues.

People, mostly teenagers, pushed past them in the dark, giggling, groping, and shrieking like joyful heretics at a clown inquisition. Someone pinched Sammy’s bottom and he jumped.

“Was that you?”

“What?” said Stilton, her voice sounding about ten feet away.

“Nothing,” Sammy said. “I think I mighta just made a friend. Stay there, I’ll come to you.”

He found her in the dark and they kissed like they’d been separated for months, clinging to each other as revelers bumped into them, shrieked and laughed and stumbled on. They blundered together through another set of baffles, these made of some kind of black gauze, which felt like spiderwebs against their faces, onto a dimly lit floor that shifted and tilted, sending them staggering one way, then stumbling another.

“I don’t think I’m drunk enough to walk this way,” said the Cheese.

“Relax, ma’am, you’re in good hands,” Sammy said. “I’m a bartender.”

He pulled her through the next door and ducked under the outstretched hand of a moaning mummy that pivoted on an axis at his waist and swung his arm back, just missing delivering a backhand to the Cheese. Sammy pulled her down just in time and they crouched beneath the bandaged automaton. The mummy moaned again.

“This mug’s got a moo box in him,” said the Cheese.

Sammy pulled the pint from his overcoat and unscrewed the cap. “Pardon?” he said.

“A moo box,” said the Cheese, taking the pint from him. “We sell them at the five-and-dime. It’s like a little can and when you turn it over, it moos like a cow.”

The mummy waved over their heads again and moaned.

“That does sound like a cow,” Sammy said.

“Moo box,” the Cheese explained. She pointed at the pint of Old Tennis Shoes. “No chaser?”

“Rehearsal’s over,” Sammy said.

She went a little cross-eyed as she took a swig, scrunched up her face like a kid eating a lemon, then shook her head until the burn settled down. There were tears in her eyes when she held the pint out to Sammy as if it contained a cocktail of nitroglycerine and monkey spit, which is to say, with careful disgust. “Smooth,” she gasped.

“Good for cleaning engine parts, too,” Sammy said, braving a swallow himself and capping the bottle. “Let’s get out of here.”

They raced away from the mooing mummy and made their way across the ceiling of an upside-down room and through a mirror maze to stumble, arm in arm, out onto the midway. The smell of sea air, popcorn, cotton candy, and cigarette smoke washed over them. Sammy bought them snow cones, red for her and blue for him, and, at Stilton’s suggestion, doctored the chilly treats with the last of the Old Tennis Shoes.

“Not bad,” said the Cheese.

“Could use some more blue,” Sammy said.

They walked by the rides and souvenir stands, and tried to find takers for bets on the merry-go-round.

“I’m giving six-to-five odds on the funny-lookin’ kid on the camel!” Stilton called, waving a fan of Skee-Ball tickets in the air to show she was legit.

“I think that’s a giraffe,” Sammy said.

“Five-to-six on the funny-lookin’ kid to win, then,” said Stilton.

Sammy pulled her away before she could find any takers and they ended up in front of a caricature artist, who sat on a stool, wearing an artist’s

smock and a beret.

“Pinup of the little lady, sir. Only a buck.”

“I don’t know . . .” Stilton tried to walk away.

“I think she’s worth giving a second look,” said the artist. “Don’t you?”

“Absolutely,” said Sammy. He swung Stilton around by the arm. “Come on, Toots, I think you’re worth it, don’t you?”

“Don’t call me—” She caught herself falling for the bait. “Aw, hell.” She slurped the last of her snow cone, handed the soggy paper wrapper to Sammy, then sat down on the stool opposite the artist and let her trench coat fall off her shoulders.

“Color me pretty,” she said.

A look passed between Stilton and the artist that made Sammy think she might slug the guy.

“No work for me, ma’am,” said the artist, and he commenced drawing, holding his drawing board out of Sammy’s sight.

“Fine,” Sammy said. He walked away and fought with a half a book of matches to get a cigarette lit, noticing that the breeze had changed directions and was blowing offshore—it was warm, a rare condition on a summer night at the San Francisco beach.

“How ’bout you undo a button or three in the front there, Toots?” said the artist, when he thought Sammy was out of earshot.

“How ’bout I bop you in the beezer so hard it spins your beret around?” said the Cheese.

“Jeez,” said the artist. “No need to get tough.”

“And don’t call me Toots,” said the Cheese.

The artist finished his sketch about the time that Sammy was grinding out the butt of his smoke on the gravel of the midway.

“Voilà!” said the artist, in perfect fucking French. He flipped the drawing around.

Sammy took a look, then took a step back and whistled. “Holy moly.”

“You’re a lucky guy,” said the artist.

“Yes I am,” said Sammy.

The caricature portrayed Stilton in the pose of the classic Rosie the Riveter she can do it poster from the war—a blonde flexing a bicep, her hair tied up in a polka-dot bandana, the classic chambray shirt—except this Rosie was facing the artist, not looking over her shoulder, and the shirt was unbuttoned to the point that exaggerated bits of the Cheese were about to burst out for the world to see. It was Stilton all right, but rounder in the places where she was round, and sharper in the places where she was sharp: drop-dead sexy.

“That should be on the side of a bomber or something,” Sammy said.

“That’ll be a buck,” said the artist.

“You got it.” Sammy handed the guy a dollar. The artist tore the drawing from his sketchbook and started to roll it up.

“No, not yet,” Sammy said. He took the drawing, held it up, and compared details with the model, his eyes darting from Stilton to the drawing and back. “I need to look at this Rosie.”

“You two have a good evening, sir,” said the artist with a wink to the Cheese.

“Wendy,” Stilton said as she stood and joined Sammy in admiring the drawing, turning her back on the artist. “Rosie the Riveter was for girls who worked in airplane factories. In the shipyards we were Wendy the Welders.”

“What a dame,” Sammy said. Then he turned from the drawing and kissed her.

“You like it?” She pouted with anticipation.

“I like the model,” Sammy said. “I like the model a lot.”

“Let’s go for a walk,” Stilton said.

“It got warm out,” Sammy said. “You notice?”

“Oh yeah,” she said.

Sammy rolled the drawing up and fixed it with a rubber band the artist had given him and tucked it in his pocket. They walked arm in arm around Playland at the Beach, then out of the park and up into the dunes. They found a sheltered hollow where all they could see was the stars and sand, and calliope music from the merry-go-round sailed over them on a warm offshore wind. They lay down between her trench coat and his overcoat, wrapped the stars around them like a blanket, and made love until time disappeared.

* * *

Time returned, just before dawn, dressed in a chill fog, and Sammy awoke to the caricaturist’s drawing poking him in the ribs. “Hey,” he said. “How did that guy know you worked at a shipyard during the war?”

10

Surprise

When Sal Gabelli came through the back door of the saloon, he found a wooden crate, about three feet square, with the words DANGER! LIVE REPTILE! stenciled on the side in big, black letters.

“What wacky shit is this?” Sal said to himself and the four mutts who were waiting behind him outside the door. Sal had been experimenting with his dog pizza idea, and dogs of various sizes and colors had been attracted to his experiments. Now they met him at the door every morning when he opened the joint and waited for the next incarnation of dog pizza cooked up by Sal’s wife the night before. “No pizza today, ya mooches,” said Sal, and he slammed the door in their faces.

Folle donnola! (crazy weasel), the dogs barked in chorus, before they kicked Sal from their hind paws like shit-stained grass and wandered off to find better fare. (It is well known that all North Beach dogs bark in Italian.)

There was an envelope stapled to the crate, addressed to Sam Tiffin, care of Sal’s, with private stamped upon it in red. Sal considered, for three full seconds, not opening the envelope, before constructing a five-pronged rationale for doing so, which was as follows:

It is addressed to my saloon.

Sammy took the night off.

The relief bartender, Bennie, does not do my side work, and is, therefore, a bum.

The gimp has a lot of goddamn nerve receiving packages here.

Fuck him. Pookie O’Hara is probably going to put him in a sack anyway.

Sal ripped the envelope from the crate and paused an additional two seconds while he considered carefully steaming it open, then ran through his five rationales, settling quickly upon No. 5, and tore it open. The letter inside read:

Sammy Boy:

Let someone who knows what he’s doing open this.

These buggers are quick as lightning and twice as deadly.

Hope your business venture works out.

Headed to China. Be back in September. See you then.

Cheers,

Bokker

Sal read the letter again, looked at the crate, then read the letter again, then set it on the crate. He could always say he found it that way. No harm, no foul. It was open when I came in, Sal practiced in his head. Must have been Bennie. You ask me, that guy is a bum. Never changes out the keg at the end of his shift. That figured out, Sal made his way over to the tap, put a pilsner glass under it, gave it a pull, and sure enough, the tap sputtered and spit foam into the glass, then hissed, empty. A bum, I tell ya!

Now Sal was faced with the dilemma of switching out the keg, which he did not want to do, or opening the crate, which he very much did. What kind of scam was Two-Toes running, anyway? Who did he think that DANGER! LIVE REPTILE! rigmarole was going to fool? And why not have it sent to his house instead of the bar? Unless Two-Toes had counted on it arriving when he was working, and it had arrived when Bennie was filling in, so the relief bum had accepted the crate. That had to be it.

Had Two-Toes found a business angle and not cut Sal in? Would he dare? Were the warnings on the crate just to keep the law from checking the package? Did he owe the gimp the privacy? Hmmm . . . Had Sammy come through putting the Dorothys together for the Bohemians? He had not. That task had fallen one hundred percent on Sally Gab. Two-Toes might have made a nice cache of cabbage if he’d done his part, but he hadn’t. See No. 5. Fuck him. He didn’t deserve discretion.

Sal returned to the back room and eyed the crate. It had to be illegal, or at least shady, either one of which put it in Sal’s domain, because he was the implied boss of all things shady and/or illegal that took place in the saloon. Whatever game Two-Toes was running, Sal was taking a piece.

He gave the crate a little bump with the heel of his hand and it tip

ped up an inch, then thumped to the tile. It wasn’t heavy. So it wasn’t booze. Wrong-size crate, and besides, the only kind of booze you had to smuggle anymore was absinthe, and nobody wanted it anyway because it tasted like ass and cost too much for something that might poison you dead. He gave the crate another tip and let it thump down. Nope, nothing heavy. He’d be surprised if it was even full. Sal grabbed the crate by two corners and gave it a good shaking—a sliding, really. There was definitely something in there. It sounded like straw.

They kept a short crowbar on a hook above the sink that they used to pry open the crates of the few liquors that still shipped in wooden boxes, mostly Scotch and a few dago reds that they stocked for the neighborhood old guys. That would do. Sal snatched the crowbar from its hook and returned to the crate. He worked the crowbar under one corner of the lid, popped it with his palm to give it some bite, then put his weight on it. The nails screeched and the corner of the crate came up an inch. Once a bootlegger, always a bootlegger, Sal thought. How many crates had he had to pry open fast during Prohibition? Canadian whisky sailed into the bay on pleasure craft and was quickly repackaged in fruit and vegetable crates, under real fruit and vegetables, before it was rowed to shore.

Sal attacked the next corner with the crowbar and levered it down hard. Nails creaked. The lid lifted two more inches. He worked the short end of the crowbar around the edge of the lid like he was opening a big can, and the lid came loose. Sal leaned the lid against the side of the crate, then peered in. Nothing. Half-full with those curled wood turnings they used to pack dishes and teacups. Nothing was nesting in it. Just a box full of straw, really. But it had been heavier than that.

Sal grabbed a handful of straw and held it aloft. Nothing. He poked at the rest of the straw, stirred it around, hooked the crowbar into it, and turned some of it over. Nothing. But there, in the corner, something brown. He leaned into the crate and caught it with the tips of his fingers. A canvas bag.

“Two-Toes, you fuckstick,” he said aloud, his voice a prelude in disappointment. The canvas bag was tied at the top, and while it may have once held fifty pounds of flour or rice, now it held nothing at all. In fact, one corner of it was torn, tattered, as if it had been chewed by rats. There was a noxious smell coming off it, too. Sal tossed the sack toward the trash can by the back door. It missed, by more than a little, and he angrily hooked it with the crowbar and slung it into the can. Then he saw something move out of the corner of his eye.

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christs Childhood Pal A Dirty Job

A Dirty Job Sacré Bleu

Sacré Bleu Bite Me: A Love Story

Bite Me: A Love Story You Suck: A Love Story

You Suck: A Love Story Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story

Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story The Stupidest Angel

The Stupidest Angel Coyote Blue

Coyote Blue The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove Secondhand Souls

Secondhand Souls Shakespeare for Squirrels

Shakespeare for Squirrels Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings

Fluke, or, I Know Why the Winged Whale Sings Island of the Sequined Love Nun

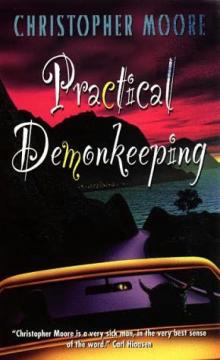

Island of the Sequined Love Nun Practical Demonkeeping

Practical Demonkeeping The Serpent of Venice

The Serpent of Venice Noir

Noir Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal Bite Me

Bite Me Bloodsucking Fiends

Bloodsucking Fiends You Suck ls-2

You Suck ls-2 Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1

Bloodsucking Fiends ls-1 The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror

The Stupidest Angel: A Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2

The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove pc-2 You Suck

You Suck Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art

Sacre Bleu: A Comedy d'Art Lamb

Lamb 1867

1867 Bite Me ls-3

Bite Me ls-3 Practical Demonkeeping pc-1

Practical Demonkeeping pc-1